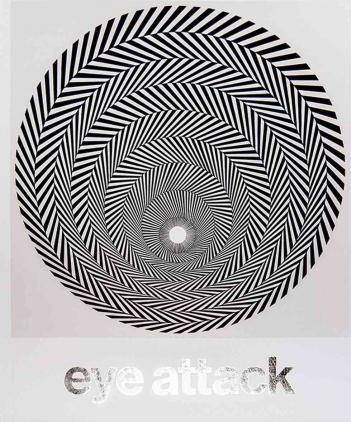

Op art had its inception in the middle of the 1950s and its glory days in the 1960s, when it established itself internationally across political and cultural contexts. These artists — among them Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley — were preoccupied with science, the psychology of perception and the new technology of the time. This dynamic approach to the world is also the essence of kinetic art, which broadly describes works of art that incorporate movement, whether literally or as an illusion. Optical and kinetic art developed hand in hand, in an abstract, geometrical language of form, using new industrial materials and techniques, and share a strong interest for the anti-static and the direct sensory experience. These movements have left their marks upon contemporary visual art and culture. The direct appeal to the senses is unabated — in this book, the catalogue for a current exhibition at Danish Louisiana Museum of Modern Art — the movement’s place in (pre-digital) cultural history, its heritage in contemporary art and the appeal it still holds is discussed in essays by Tine Colstrup, Matthieu Poirier and Joe Houston. Michael Juul Holm interviews artists Carlos Cruz-Diez, Francois Morellet and Heinz Mack, as well as younger artists John Armleder, Olafur Eliasson and Julie Riis Andersen, all of whom share a kinship with historical Op art.

- / Article author

- / Article author

- / Article author

- / Article author