Art in the City: The History and Contemporary Practices of St. Petersburg Performance

In December 1989, the New Academy of Fine Arts appeared in St. Petersburg. Its founder, the artist Timur Novikov, proclaimed neo-academism as a new principle of life-building, offering the cult of beauty as a salvation from the coming crisis in the contemporary art world. Asserting the power of art as an ideal world order, Novikov formed a whole new society embodying this, the heroes of which were the neo-academic artists Georgy Guryanov, Konstantin Goncharov, and Denis Egelsky.

In his book about Russian art of the perestroika period, The Irony Tower, the American writer Andrew Solomon noted the striking contrast between the appearance of Moscow and Leningrad artists. When he first arrived in Leningrad, he was amazed at how stylish the artists were, comparing Timur Novikov’s circle with the world’s leading fashionistas. The spirit of dandyism triumphed in this community in the late 1980s, when the “New Artists turned from ‘wildness’ toward a new romanticism, secularism, and popular culture.”[1]. Solomon wrote about Leningrad as a very beautiful city, where “beauty itself is an amazing gift.”[2]. Timur Novikov turned this beauty to his advantage, taking the classical architecture of the city of St. Petersburg (the original name was returned in the early 1990s) as a starting point in “reviving the former luxury and serving the cult of the beautiful.”[3] Mastering this new space, the neo-academicians had the opportunity to live among historical architecture, getting into buildings appropriated by the Soviet government, squatting apartments with stucco molding and fireplaces that were due for renovation, and turning palaces and parks into sets for life and creative projects.

The behavior of artists also changed. They began to study the works of old masters, visit the Mariinsky Theater, and dress up in beautiful outfits, creating a sharp contrast with unsightly reality and breaking down the boundary between art and everyday life.

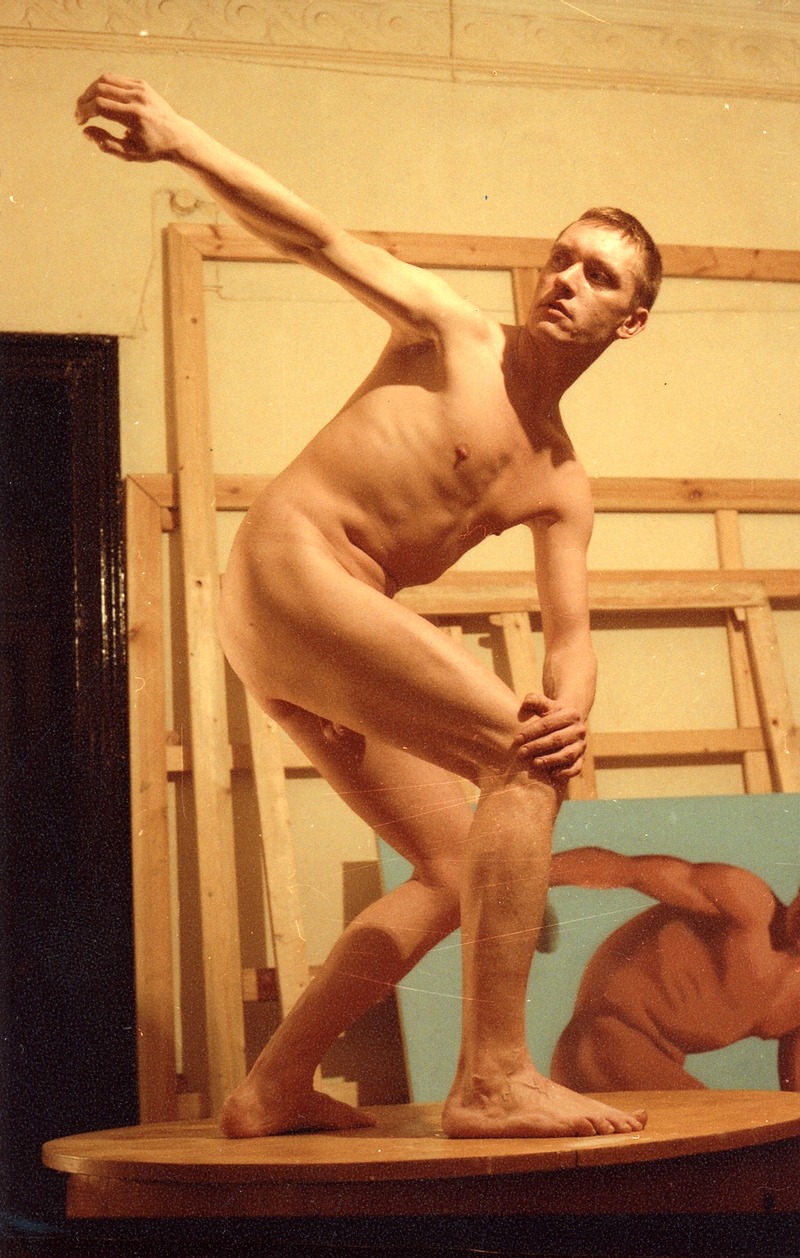

The main dandy of St. Petersburg in the early 1990s was Georgy Guryanov. Fascinated by the image of the “strict young man” from the film of the same name by Abram Room and the aesthetics of Soviet athletes who embodied youth and vitality, Guryanov endlessly reproduced them not only in his painting but also in everyday life. Behind his clothes and demeanor, which always provoked admiration, there was a whole strategy of self-presentation, expressed by the words “my work of art is myself.”[4] This was echoed by Timur Novikov, who, in one of the first neo-academic manifestos, stated that transformations “need to start with yourself, here and now.”[5]. He and the art critic Andrei Khlobystin played at dandyism, walking the streets of St. Petersburg in tuxedos and top hats and with lorgnettes, and canes. In the mythology of early neo-academism the dandy is but also a provocateur. This ironic dressing up transformed classical culture, which, according to the neo-academists’ predecessors was “boring," into a cheerful masquerade, continuing the tradition of urban eccentrics and originals. They found their unusual outfits in the numerous second-hand stores that flooded the city in the early 1990s. There was even one in Borey Gallery. Plus, the artists already had the money for expensive designer items, and trips abroad opened up access to original shops and vintage clothing boutiques. Andrei Khlobystin’s son still has a shirt bought in a special store "for the dead in Times Square in New York.”[6].

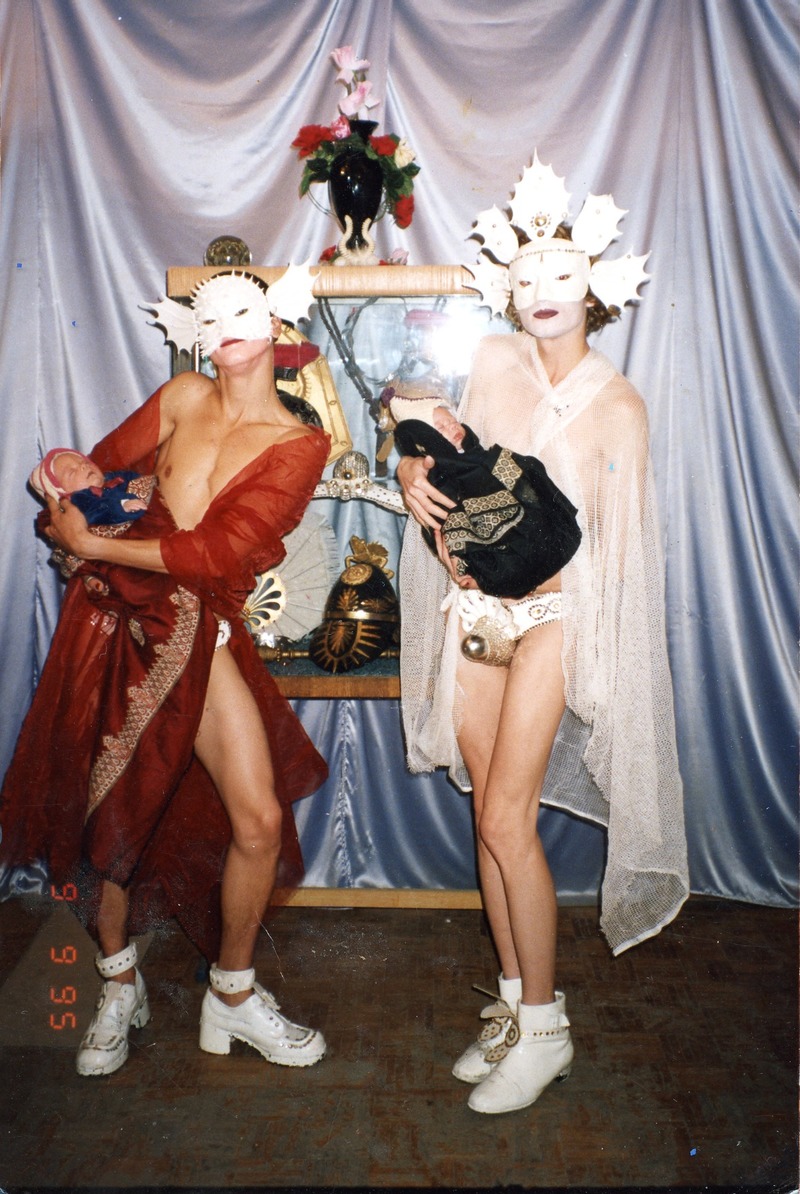

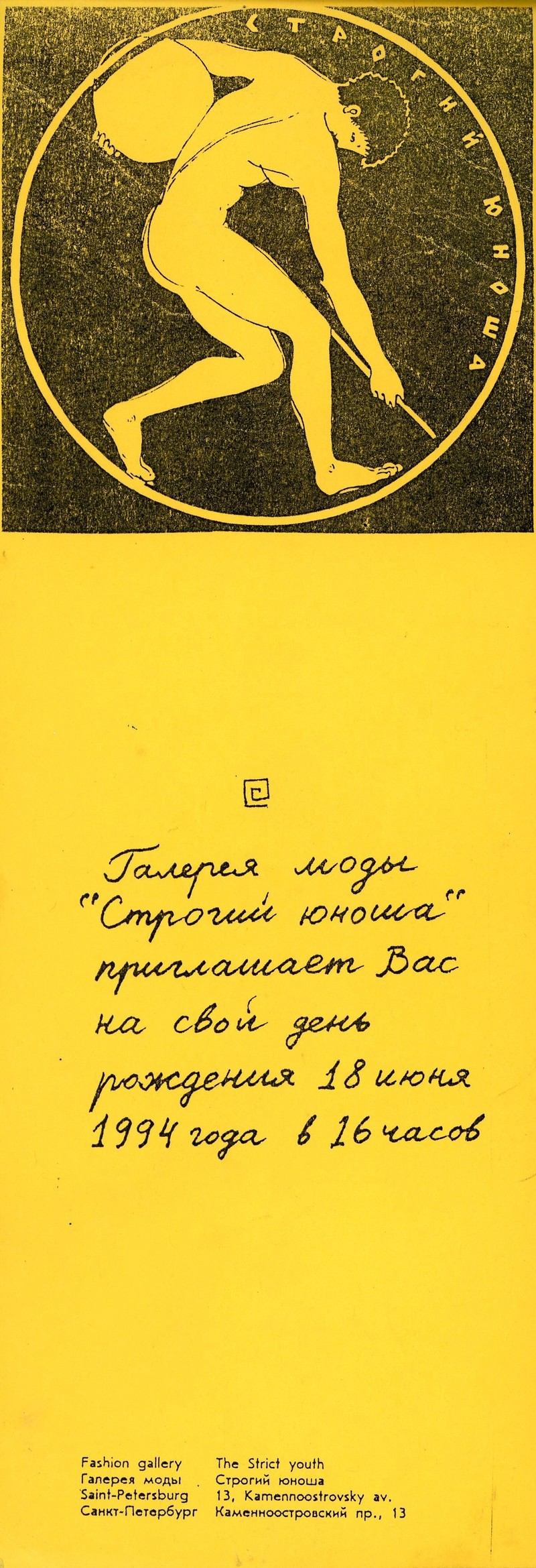

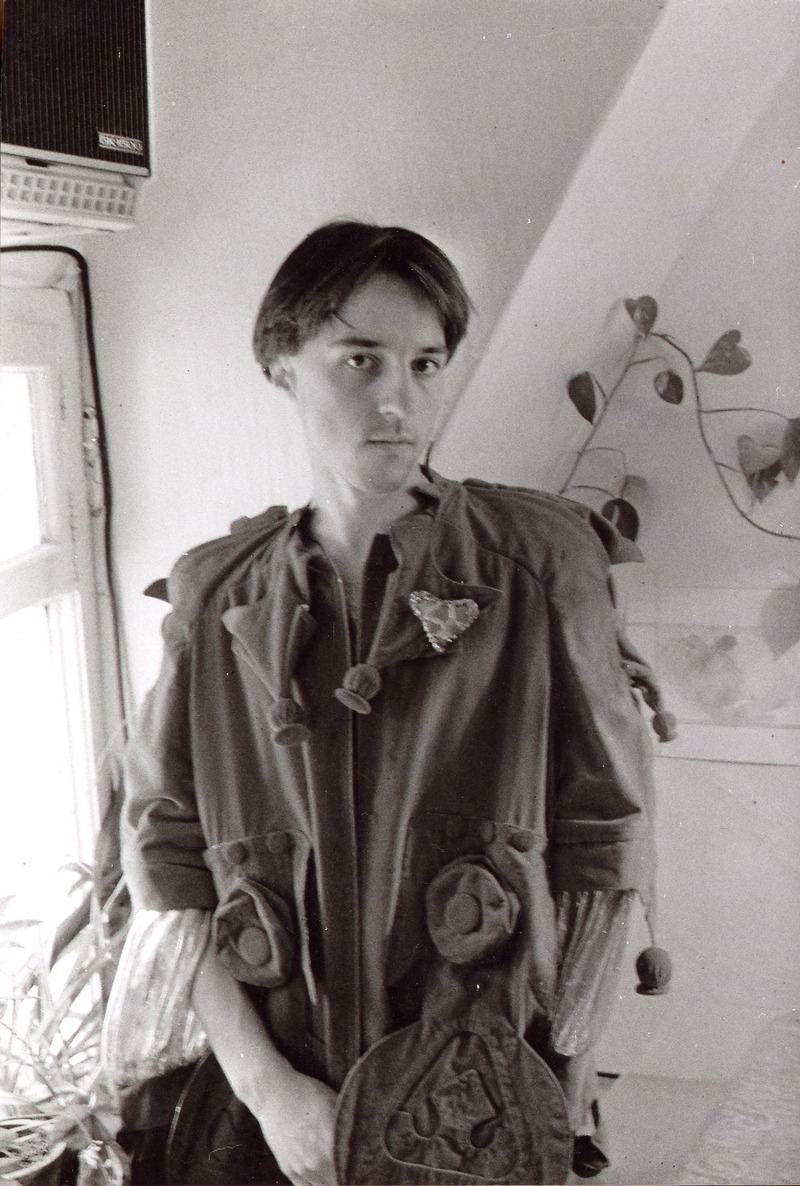

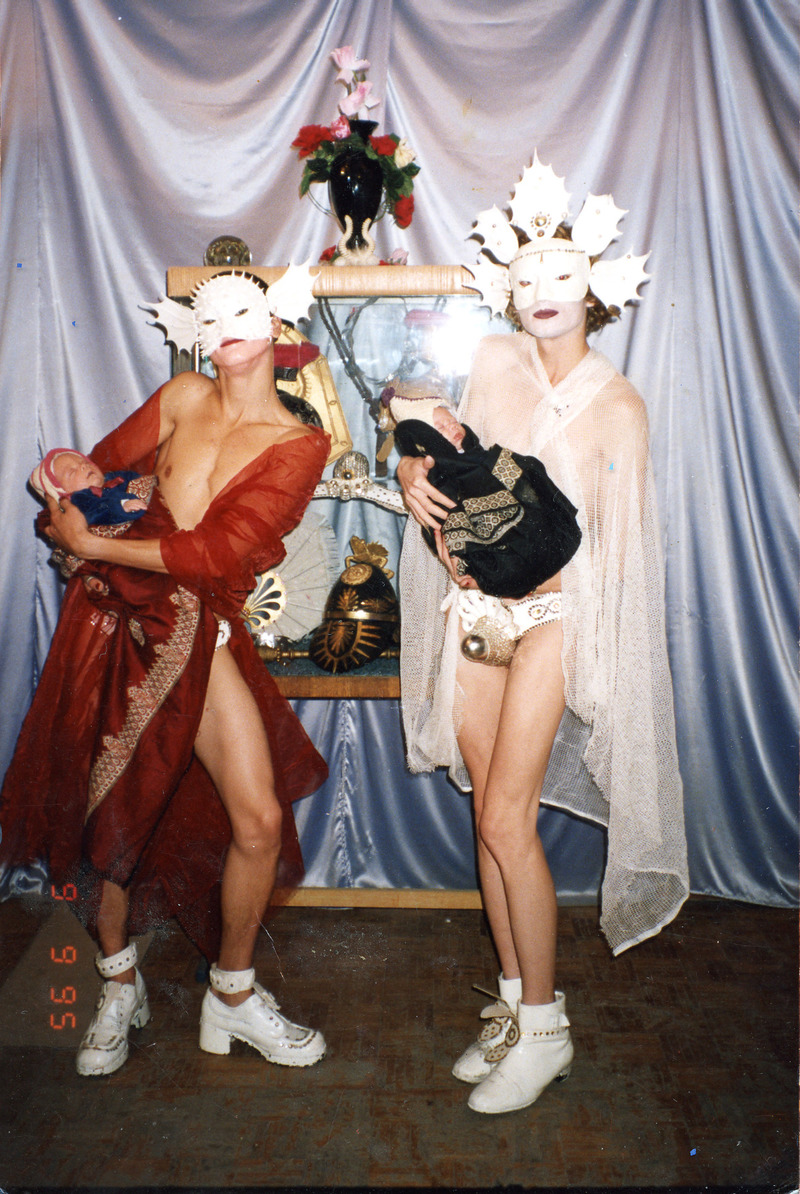

The feeling of a masquerade was also created by the luxurious outfits of Konstantin Goncharov, who became the chief fashion designer of the New Academy in the first half of the 1990s. Goncharov's creative career began in the late 1980s, when he collaborated with Zhanna Aguzarova and the group Kino, creating costumes for their performances. In 1987, Goncharov met Timur Novikov and later became his closest associate. They influenced each other. Thanks to his friendship with Goncharov, Novikov became increasingly interested in classical art, in particular ballet. And Goncharov and Alexey Sokolov, with the support of Timur, opened the Strict Young Man Fashion Gallery, which was a central location for bohemians for a number of years. Art critic Ekaterina Andreeva called Goncharov a "radical aesthete," comparing his creations to works of art, the components of which were spectacular fabrics and an incredible cut.

It was not easy to find original fabrics in the 1990s. Alexey Sokolov recalls hunting for them everywhere. They looked in stores where experimental samples, Indian shawls or Uzbek silks could suddenly appear on sale, or in thrift stores where grandmothers handed over vintage things. But Goncharov's talent meant he could also work with banal Soviet fabrics. An example is the so-called gymnasium dresses made of simple brown cloth. They were transformed by original inserts with photos of ballet dancers from the collection of Timur Novikov. Goncharov often complemented his outfits with hidden details—"secrets"—such as an unusual lining or a pocket that only the owner of the garment knew about. He achieved recognition and international fame after creating costumes for the project The Golden Ass, for which he was awarded the title “Best avant-garde artist-95" at the First Moscow International Festival of Avant-Garde Collections ALBO-Fashion. Outfits from Strict Young Man become a sign of involvement in the world of contemporary art. Among its clients were St. Petersburg artists and bohemian fashionistas from different countries, including curator Kathrin Becker, aristocrat Francesca von Habsburg, Princess Katya Galitzine, American gallery owner Jane Lombard, and others.

Living everyday life as part of an artistic action led to the creation of "avatars" by artists, on whose behalf they created and communicated with the world. A striking example of such a strategy is the artist Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, whose first public appearance as the legendary blonde took place in 1990 at a party in the Communications Palace of Culture. Then the St. Petersburg Marilyn began to appear more and more often in the city: on Nevsky Prospekt of an evening, in the club Tantspol, at the opening of exhibitions, and in broadcasts by Pirate Television.

Such reincarnations and freedom in daily life led to the artists of the New Academy having followers: party-goers organized costume parties, original outfits were worn by students of the New Academy and their friends, the group Factory of Found Clothing opened the Traveling Things Store. Andrei Khlobystin believes that Timur Novikov and his allies created a new subculture of fashionistas and aesthetes, and Ekaterina Andreeva calls St. Petersburg in the first half of the 1990s a city of "extreme aestheticism," which "returns to its metaphysical goal—to broadcast the dream of the beautiful, to draw the horizon of the ideal in the Hyperborean northern latitudes."[7]. But as soon as this became a trend, the main actors left the stage and by the mid-1990s Novikov had turned a new page in neo-academism, reincarnating from a dandy into an old man with an ax-cane, the former revelry replaced by a “new seriousness," to which most of the neo-academists would gradually turn.

[1]. A. KHLOBYSTIN, “SOBLAZNENIE I RAZOCHAROVANIE” IN SHIZOREVOLIUTSIIA. OCHERKI PETERBURGSKOI VIZUAL’NOI KULTURY VTOROI POLOVINY XX VEKA (ST. PETERSBURG: BOREY ART, 2017), P. 65.

[2]. A. SOLOMON, THE IRONY TOWER. SOVETSKIE KHUDOZHNIKI VO VREMENA GLASNOSTI (MOSCOW: AD MARGINEM PRESS, 2013), P. 107.

[3]. E. ANDREEVA, “KRUGLYI GOD,” MOSCOW ART MAGAZINE, 1, 1993, HTTP://MOSCOWARTMAGAZINE.COM/ISSUE/45/ARTICLE/872.

[4]. “GEORGY GURYANOV: ‘MOE PROIZVEDENIE ISKUSSTVA — YA SAM’,” SOBAKA.RU, 2010, HTTPS://WWW.SOBAKA.RU/OLDMAGAZINE/GLAVNOE/17562.

[5]. A. KHLOBYSTIN, “PESN’ O NEOAKADEMIZME,” IN SHIZOREVOLIUTSIIA. OCHERKI PETERBURGSKOI VIZUAL’NOI KULTURY VTOROI POLOVINY XX VEKA (ST. PETERSBURG: BOREY ART, 2017), P. 84.

[6]. FROM PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN THE AUTHOR AND ANDREI KHLOBYSTIN.

[7]. E. ANDREEVA, “LENINGRADSKII NEOAKADEMIZM I PETERBURGSKII ELLENIZM,” NOVAYA AKADEMIIA. SANKT-PETERBURG (MOSCOW: EKATERINA CULTURAL FOUNDATION, 2011), P. 52.

The project Art in the City: The History and Contemporary Practices of St. Petersburg Performance was developed by Anastasia Kotyleva and Maria Udovychenko for the podcast of the same name presented on the Museum’s booth at the 9th Cosmoscow International Contemporary Art Fair.