This material is based on interviews with former employees of Inclusive Programs Department. The interviews were recorded in 2022 and 2023 as a part of the project Garage Chronicle. The material aims to provide an overview of the department's development, drawing on memories and opinions of people who were directly involved.

Interviewees:

Maria Sarycheva was manager of educational programs for the professional community from 2013 to 2015 and a coordinator in Inclusive Programs Department from 2015 to 2016.

Galya Novotortseva was a custodian from 2012 to 2014, an administrator in Garage Education Center from 2014 to 2015, and manager of inclusive programs for blind and partially-sighted visitors from 2015 to 2018.

Alexandra Philippovskaya was a freelancer in Inclusive Programs Department from 2016 to 2017, an assistant in the department from 2017 to 2018, and a coordinator from 2018 to 2021.

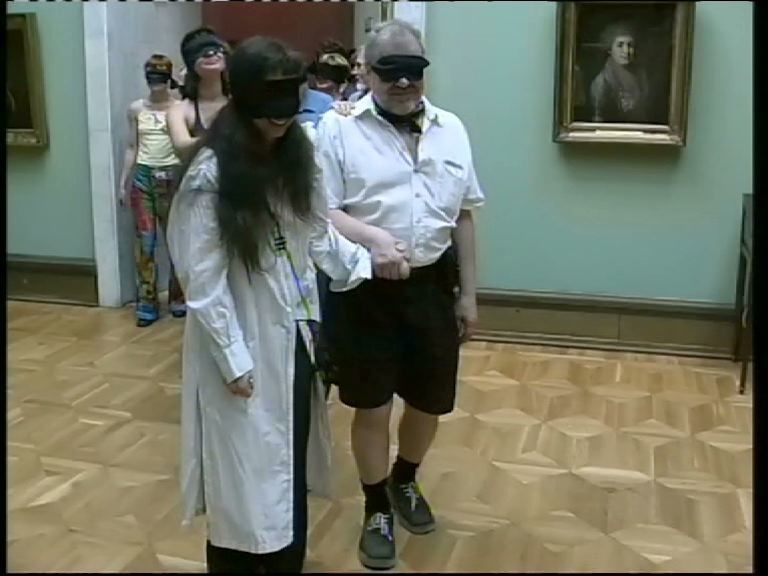

The first experience of the integration of inclusive practices at Garage was part of the public program for the exhibition The New International (2014). The education program for the exhibition included a project by independent curator Maria Kotlyachkova and the Swedish art group Supramen, The Supramen Tour. The idea behind the project was to blindfold sighted, partially-sighted, and blind visitors during guided tours in order to focus on the meaning and sense of the artworks and to seek an alternative approach to artistic communication. As Maria Sarycheva recalls, “We realized that we were inviting people who had never been to a contemporary art museum. We invited teenagers from a residential school for partially-sighted and blind children. At that time we knew nothing about blind people; not how they perceive information or how we should talk to them. The divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ was enormous.”

The team considered the experience unsuccessful, but after discussing it they decided that it was important to consider the diverse experiences of partially-sighted and blind people. At the same time, Anastasia Tarassowa of Garage Research Department offered to run the workshop Invisible Experience, which took place on October 10–12, 2014. It focused on exchanging experience of developing education programs for blind and partially-sighted visitors and was organized by Anastasia Tarassowa, Maria Sarycheva, and Anastasia Mityushina. Speakers included Katya Sudets, Ana Krepel-Velimirović, Anya Winter, Anastasia Tarassowa, Evgen Bavchar, Anna She, and Alisa Oleva. The video documentation of Yuri Albert's performance Blindfolded Museum Tour was shown. On October 8–9, 2014, Garage hosted the masterclass Touching Sculpture facilitated by Anna She, founder of Samo art therapy studio, who presented techniques for developing empathy, appreciation, and attention for partially-sighted and blind people and their families.

After the workshop, the first adapted programs began to appear at the Museum. Test tours for blind people were offered during the exhibition Russian Performance: A Cartography of its History and public tours were launched during the exhibition Grammar of Freedom / Five Lessons. They were as a personal initiative of staff pf Garage Education Department, who actively integrated into diverse communities united by the experience of disability. By the time the Inclusive Programes Department was created, the Museum had already offered tours for blind and partially-sighted and deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors. Galya Novotortseva, who later became the manager within Inclusive Programs Department for blind and partially-sighted visitors, produced tactile models for tours and mediations with blind and partially-sighted people on her initiative.

Garage Inclusive Programs Department was officially separated from Education Department on September 1, 2015 (N.B. In 2023, Inclusive Programs Department was renamed Education and Inclusive Projects Department.) The reason was a strategically important desire not only to develop programs accessible to disabled people but also to improve the quality of their experience as visitors. Maria Sarycheva recalls how the idea of the department arose: “Some time in August, during a weekly meeting of department heads, Anton Belov (Director of Garage) called me into the room and said, ‘Are you aware that we have a huge number of deaf people coming to the building? We have over 500 deaf people.’ I said that we didn’t. At that time, we already had tours translated into Russian Sign Language. Translator Vlad Kolesnikov worked together with a guide. It was impossible for so many deaf people to come to us. And then it turned out that the deaf community is a linguistic one. News spreads fast there. Earlier, museums were not part of the community’s cultural activities. And here was a Museum of Contemporary Art where everything was bright and visually attractive and although it was unclear what was going on, it seemed like the whole community visited, so others started visiting too. A huge number of deaf people came, not knowing what was going on. They just wandered around. The security guards, cloakroom staff, and receptionists did not know how to communicate with them, and at some point it became a problem. So, Anton said, “Let’s create a department. You should lead it.” I was like, “Okay.” At the same time, I thought, “What’s going on?!” I called Vlad [Kolesnikov] and Galya [Novotortseva] and we sat down to set out our expectations. Up to then we had already been actively involved in various communities. We understood what the obstacles were, what was missing other than tour activities, and what else we could offer visitors. […] We took on Vlad and Galya. The three of us started work.”

Maria Sarycheva became coordinator of the department. Vlad Kolesnikov, a speech pathologist and translator of Russian Sign Language, worked on programs for deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors. Galya Novotortseva covered the blind and partially-sighted visitor programs. During that period, Galya was also involved in working with visitors developmental disabilities. We designated the first areas of work based on the fact that each of the identified audiences had accessibility requirements that overlapped. The personal interests of staff were also considered.

Also in 2015 (September 28–30), Inclusive Programs Department organized the first international training event, Experiencing the Museum at Garage, which later transformed into the annual conference of the same name. The training event aimed to improve the accessibility of museums for deaf, hard-of-hearing, blind, partially-sighted, and deafblind visitors. Experts from Russia, the UK, and the USA took part.

Working with Blind and Partially-Sighted Visitors

Novotortseva’s main tasks were “gathering an audience, disseminating information about projects, and consulting with the curators on the selection of artworks to be transformed into tactile models, the creation of models, audio descriptions, and the design and running of tours.”

The specialists working with blind and partially-sighted visitors adapted several exhibitions during one exhibition season. All the large shows, which occupied the entire space of the Museum, were adapted. When the Museum held several small exhibitions in parallel, only one or two of them were selected for adaptation. Galya elaborates on the selection process: “I proposed to adapt the most visited exhibitions, by which I mean not those visited by disabled people but by the all visitors. We tried to prioritize famous artists or popular exhibitions. We wanted to create a situation where your sighted friend goes to an exhibition and then tells you about it. We encouraged blind people to attend exhibitions attracting more interest and attention from the media. [...] Since we usually did not have much time from the moment we had enough information on the exhibition to the tour launch, sometimes I would realize that we would not be able to do anything decent for one exhibition while being able to do something good for another. When exhibitions shared the same theme, we chose for adaptation two objects in one exhibition, two objects in another, and made a survey tour of all projects at the Museum.”

One way to adapt an exhibition is to develop and manufacture tactile models accompanying the works on display. They are necessary because tactile perception is one of the main sources of information for many blind and partly sighted people. However, the creation of tactile models can meet with resistance from artists or institutions. The production and use of tactile models in Russian museums often leads to discussions, primarily because legislation obliging art institutions to be accessible to visitors is open to interpretation. The status of the tactile model from the point of view of copyright is also problematic (For more information on this topic, see the discussion “Production of Tactile Models: Legal Aspects” between Maria Shchekochikhina, Galya Novotortseva, Dmitry Nikitin, and Mikhail and Olga Shu.) Inclusive Programs Department has so far always been able to reach agreement on the creation of tactile models. They are now kept in the Museum’s institutional archive.

Sometimes it was possible to use readymade objects. During Japanese artist Takashi Murakami’s exhibition Under the Radiation Falls, in addition to manufactured tactile models, the department used kaiju monster figurines, purchased by Galya Novotortseva in Japan. As she recalls, “It was fun because the [blind] kids visiting us watched anime but could not always imagine what it looked like, so it was great for them to interact with figures from anime and imagine how the animated characters looked.”

Another way to adapt exhibitions is to record audio descriptions, detailed verbal descriptions of visual images based on a technique that includes narration from the general to the particular, but without a subjective evaluation from the commentator about the objects. Galya recalled the adaptation of Yayoi Kusama’s exhibition Infinity Theory, which featured two installations. The first, Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, was a room with mirrored walls filled with thousands of lights reflected in the mirrors. The second, Guidepost to the Eternal Space, was another room in which all the walls and structures were covered with a white polka dot ornament on a red background, so that viewers were deprived of spatial orientation. The works could not be touched, and Galya Novotortseva describes its adaptation as follows: “Together with Garage Teens Team, we recorded visitors sharing their impressions: a young person would approach visitors and ask questions such as, ‘What were your impressions ?’ I recorded a standard audio description. Then we gave these recordings with very emotional responses [to blind and partially-sighted children] to listen to and they entered the installations with their parents. Most people had to go in one at a time, but we were given permission to let in blind or partially-sighted visitors with an accompanying person. So, they had listened to the visitor reactions and the audio description. They went in with their parents and heard them crying and laughing. And all at the same time... Of course, it was mainly indirect perception because they could not touch the installations, but from an emotional point of view it was cool.”

It is important to note that tactile models and audio descriptions are complementary practices and not simply interchangeable. The multisensory approach, using smell and taste as well as touch and hearing, makes it possible to perceive works of art more deeply and subtly.

As well as exhibitions, public events were adapted for blind and partially-sighted visitors by the development of tours, the recording of audio guides, and the creation of education projects.

The tours became permanent after the opening of the exhibition Russian Performance: A Cartography of its History in 2014. In 2015, the Museum launched walks for blind and partly sighted people in Gorky Park, which, according to Galya, “were part of the opening of the Museum and aimed to draw attention to the Seasons of the Year pavilion (the Museum building) and explain its architectural significance. Since I love architecture, I immediately came up with the idea of the walks for blind people. I had a ceramist friend who agreed to make tiles that were used to decorate the inside of the pavilion where the Garage office is now located, according to surviving sketches from the 1923 All-Russian Agricultural and Handicraft Industries Exhibition. But making the facades of the exhibition pavilions or the arch of the main entrance was much more difficult. I complained to Olya Shu that I needed a sculptor, and sit turned she was one. So, Olya started making these reliefs for us. Now Olya and Misha Shu have their own workshop, where they make tactile models for most of the museums in Russia.”

As a rule, partially sighted and blind visitors explore from five to eight exhibits during a tour. This is because it takes a lot of time to discuss one object, since in addition to talking about the personality of the artist, the subject of the work or the way it is made, the guide invites the audience to examine a tactile model, often one per group, and also reads aloud or improvises an audio description. Tour groups are usually small; they vary from eight to twelve people, including accompanying persons.

In 2017, two outreach programs were launched: Architecture. Accessible, an adapted course on architecture that had been available to Garage visitors without disabilities for several years, and The History of Painting. Accessible, an adaptation of the course for visitors without disabilities In the Footsteps of Contemporary Art. In addition, department staff made audio descriptions and translations of Irina Kulik’s lectures on the history of contemporary art into Russian Sign Language. As Glaya says, “Sometimes I hear very interesting stories, both from blind and sighted people. Someone starts telling me excitedly that they have found lectures on contemporary art with an audio description. I answer, ‘Yes? Really?’ There are also blind people who watch them with great interest. This is great because many people have questions like ‘Why are you doing this? Does anyone need this?’ But the most interesting thing is that several sighted people told me that they watched lectures with Irina Kulik’s audio commentary because they did not have to look at the screen while listening and doing household chores simultaneously. Or if you missed something at the Museum, you can judge from the description whether you should come and see it or not. It’s intriguing."

Unlike the community of deaf people, which is united by a common language and culture, and the communities of parents of people with developmental disabilities, adult blind and partially-sighted people do not form communities based on the experience of disability. This does not mean that blind and partially-sighted people do not interact with each other. Some may be in touch because they were in the same school class; others often unite through sports organizations. There are communities of parents of blind children functioning as the basis for connections between blind children and adolescents. However, this is why the formation of a museum audience through communication with the community turned out to be impossible, and Garage staff had to attract its audience directly. As Galya explains: “It was a , many hours of calls to everyone in the world, to every branch of the All-Russia Association of the Blind, and to all organizations that interact with blind people in any way. We made numerous attempts to convince them that the Museum was worth visiting. Over time, people who were uninterested in contemporary art and culture dropped out, and people who were interested began to form a cluster around us.”

Galya describes the first years of development of the department of inclusive programs in general and the work with partially-sighted and blind visitors in particular: “We basically did everything from scratch. We looked for all the best practice available, all the available information, discovered guides, toolkits, and so on. Based on this, we figured out how to make tactile models, how to record audio descriptions [. . .]. We learned from everyone who had experience, instead of going to one person and asking them to help as the one and only expert in the field. If we had done that we would have the opinion of a single Russian expert. As we tried to do everything ourselves, we ended up learning from various experts from the USA, the UK, the former Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Germany, and Russia. We gathered this information from everyone. This has led to a deeper understanding of tactile models, audio descriptions, and our program in general.”

Maria Sarycheva says, “We began to include those who are now called ‘people with disability experience’ in the process of creating formats intended for them, and then we learned that ‘Nothing for us without us’ is a principle used in the USA. We had been stealing, as it were, from British and American museums. From the Americans because they had the Americans with Disabilities Act, according to which a public space cannot refuse entry to disabled visitors. Otherwise, it will face inspections and litigation. We began to read materials in English on the topic and engage in active self-education.” As for the reputation of their line of work in the museum community, Galya comments, “From the very beginning we attended conferences. We were terribly impudent, telling everyone how wrong they were, reproaching the Hermitage for having a program for children but no programs for adults, like, ‘What will you do for these children when they grow up?’ However, in the end, we formed a team of museum workers with the same interests, the same goals. And then everyone else caught up after realizing that we were not just blabbermouths; we were doing something good.” Garage was the first Russian museum to create a department for inclusive programs, but it was not the first to start working with people with disabilities. Maria Sarycheva adds, “We were not the first to work with people with disabilities in the museum, but we were the first to work with disabled adults. Until the age of 18, people are registered with organizations or institutions, but as soon as a person loses the status of ‘disabled child,’ that’s it. They find themselves isolated from other people, society, and education programs. At conferences, we went on rampage: 'You are doing it all wrong; we need participatory design; we need to integrate people with disabilities.' But now, after collaborating with experienced museum workers who had trodden this path before us, I understand that we were smarty-pants with enormous resources like private funding and the symbolic capital unavailable to these museums.”

Garage staff also sought to establish professional relationships with colleagues at foreign museums. They responded with invitations to their conferences. In 2016, Maria Sarycheva, Vlad Kolesnikov, and Galya Novotortseva traveled to Pittsburgh to attend the Leadership Exchange in Arts and Disability (LEAD) conference at the invitation of Rebecca McGinnis, accessibility coordinator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2017, department staff participated in the same conference in Austin, USA. And in 2018, Garage hosted the annual international conference Experiencing the Museum, dedicated to the integration of blind and partially-sighted visitors and organized by Galya Novotortseva, Alexandra Filippovskaya, and Maria Shchekochikhina.

Working with Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Visitors

Inclusive Programs Department also works with deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors. Vlad Kolesnikov was involved in this work from 2015 to 2018. Maria Sarycheva recalls meeting him: “At some point, Vlad Kolesnikov visited us and said, ‘Why do you use the word “inclusion”? There is nothing inclusive here at all. I’m hard of hearing, and I don’t understand the experience of the contemporary art museum. What should we do about it?’ He thought I would defend myself, make excuses or start arguing. I said, ‘Vlad, it’s great feedback. Let’s sit down and have a coffee.’ That is how my friendship and cooperation with Vlad began.”

It is important to note that, as Maria Sarycheva points out in the interview, Inclusive Programs Department grew out of friendship. Maria says, “This is something that Garage always ignores. If we look at the Museum’s reader (Garage Journal Reader, an anthology published by Garage and Garage Journal focusing on accessibility and inclusion), edited by Dmitry Bezuglov, we will not find a single word about the launch of the department. It says ‘the institution did everything itself,’ but the institution consists of people and depends on connections between them, on the enormous trust between people. Institutions always ignore that.”

The Museum’s work with deaf and hard-of-hearing people involves education projects, tours, lectures, conferences, masterclasses, and discussions. One of the most important projects is the Dictionary of Contemporary Art Terms in Russian Sign Language. Since RSL lacked gestures like "installation," “performative practice," and "exhibition," which are often necessary in conversations about contemporary art, it was vital to create them, or rather to record the explanations that Russian Sign Language translators used during tours. On a global level, the project aimed to improve and enrich Russian Sign Language. A large expert group was assembled to create the dictionary. Members included Arkady Belozovsky, Tatiana Birs, Alexander Martyanov, Alexander Sidelnikov, and Antonina Pichugina. The experts collaborated with the members of the working group: Vlad Kolesnikov, Maria Sarycheva, Ekaterina Vladimirtseva, Anastasia Mityushina, Ekaterina Lazareva, and Natasha Soboleva. Maria Sarycheva says of the project, “We did a tremendous amount of work; without Vlad, it would not have been possible.” Furthermore, work also included the adaptation and translation of Irina Kulik’s lecture series with audio descriptions into Russian Sign Language.

Unfortunately, Vlad Kolesnikov refused to give an interview. Without his words, it seems impossible to tell a complete and detailed story about the initial years of working with deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors. However, his colleagues spoke about his contribution to the department. Alexandra Philippovskaya, coordinator of Inclusive Programs Department from 2018 to 2021, described Vlad as a professional with a lot of ideas and a deep understanding of the needs of the community and how to work with them, what programs need to be launched, and what aspects of foreign experience are adaptable. Since Vlad himself is a member of the community, the other members trust him. Alexandra remembered one of her favorite projects, the training course for deaf tour guides (Fall 2016–January 2018), which she coordinated. This was a unique program, the goal of which was to conduct tours in Russian Sign Language; by the deaf and for the deaf. It was supposed to be a one-year course, but lasted longer than expected. Classes were held twice a week. The prototype was the training program for deaf tour guides at Tate in London. The program was backed by institutions ready to hire or invite course participants on an ongoing basis: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, the State Tretyakov Gallery, and Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA). The course included several modules, each of which was taught at one of the institutions. Their employees gave lectures and facilitated practical seminars in the museum spaces. In addition to classes on art history, museology, and lectures based on institutional collections, the course included masterclasses on information resources, independent research, presentation skills, public speaking, and Russian Sign Language. Participants attended lectures and classes on deaf artists and their art and famous figures and trends related to disability art (an art movement whose members represent or problematize their experiences of disability). Each module concluded with a test and a tour. The indirect objective of the course was to study and use the dictionary of contemporary art terms in Russian Sign Language developed by the team at Garage and a group of independent experts. Alexandra Philippovskaya believes that the project played an important role in the development of inclusion in Russian cultural institutions, since it was the first attempt to include people with disabilities in the professional community. There had been many programs for visitors with disabilities before this project opened up new employment opportunities for deaf people in cultural workplaces and influenced the attitude of museum workers toward disabled people in general. Alexandra noted that the project was an attempt to change the paternalistic attitude to horizontal relationships.

The tour guides who completed the course created the organization Sign in the Museum in order to organize tours in sign language in various cultural institutions in Moscow and popularize art among deaf and hard-of-hearing people.

Cover photo by Olga Gauga