Art in the City: The History and Contemporary Practices of St. Petersburg Performance

In June 1995, messages about strange incidents that happened on Zhukovsky Street and thereabouts appeared in St. Petersburg newspapers: the traffic was blocked by policemen, shouts of "Fire!" were heard, smoke appeared from one house, people began jumping out of their windows, some ran back and jumped out again, and then costumed mummers and curious citizens gathered in a carnival procession, which, after walking a few blocks, ended up in the garden in the courtyard of the Fountain House.

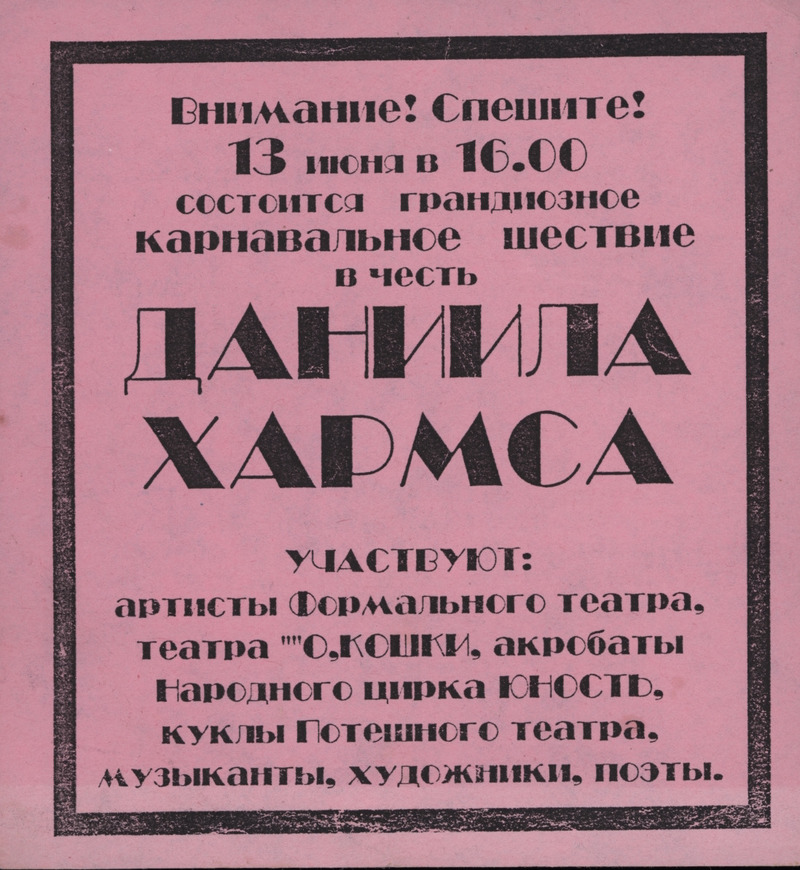

This chain of events disturbing the peace in one of the central districts of the city was part of a major festival dedicated to the master of literary paradoxes, Daniil Kharms. The organizers of the first Kharms Festival were artist Mikhail Karasik, art critic Gleb Yershov, and philologist Valery Sazhin. The main site was the Anna Akhmatova Literary and Memorial Museum in the Fountain House, which was one centers of St. Petersburg’s artistic life in the 1990s.

The writer Daniil Kharms became popular among a wide readership at the end of perestroika as one of the heroes of the Leningrad literary avant-garde and an OBERIU (Union of Real Art) participant. In the 1920 and 1930s, when he wrote most of his works, mainly his texts for children’s books and magazines were published officially. His handwritten archive was preserved by the writer’s relatives and in the late Soviet period some of his poems and prose works appeared in samizdat. It was only in the 1990s that Kharms became more widely known.

The festival organizers were passionate about the writer. Philologist Valery Sazhin worked with Kharms’ manuscripts at the Public Library, where they are kept thanks to Yakov Druskin, who preserved most of the writer’s heritage. Later Sazhin prepared the complete works of Kharms for publication and is now one of Russia’s main Kharms specialists. At the end of perestroika, Mikhail Karasik began to be interested in the genre of the artist’s book and its history, including publications of the Russian avant-garde. He made a number of lithographed books based on Kharms’ texts and named his self-organized publishing house Kharmsizdat. The young art critic Gleb Yershov was studying Pavel Filonov’s “analytical art” and was also interested in Kharms, as he was friendly with many of Filonov’s students.

The festival was conceived as a project combining different interpretations of the Kharms phenomenon and Kharms literature. Each of the organizers prepared their own program of events. Valery Sazhin organized a scientific conference, which was attended by the distinguished Kharms scholar Vladimir Erl, Lydia Druskina—Yakov Druskin’s sister, who handed over Kharms’ manuscripts to the library in the early 1980s and knew many family stories about him—and Russian and foreign literary critics and historians. Another academic event was the presentation of the book by the Swiss Slavic studies specialist Jean-Philippe Jaccard, Daniil Kharms and the End of the Russian Avant-Garde, a monograph that would be important to many researchers.

The second part of the festival was an exhibition of books based on the works of Kharms by various artists, curated by Mikhail Karasik. In addition to the author’s paper publications, the exhibition included a book in the shape of boots, a book-suitcase, a book-brick, and a book-room. The conference materials and the exhibition catalogue were subsequently published with the same cover.

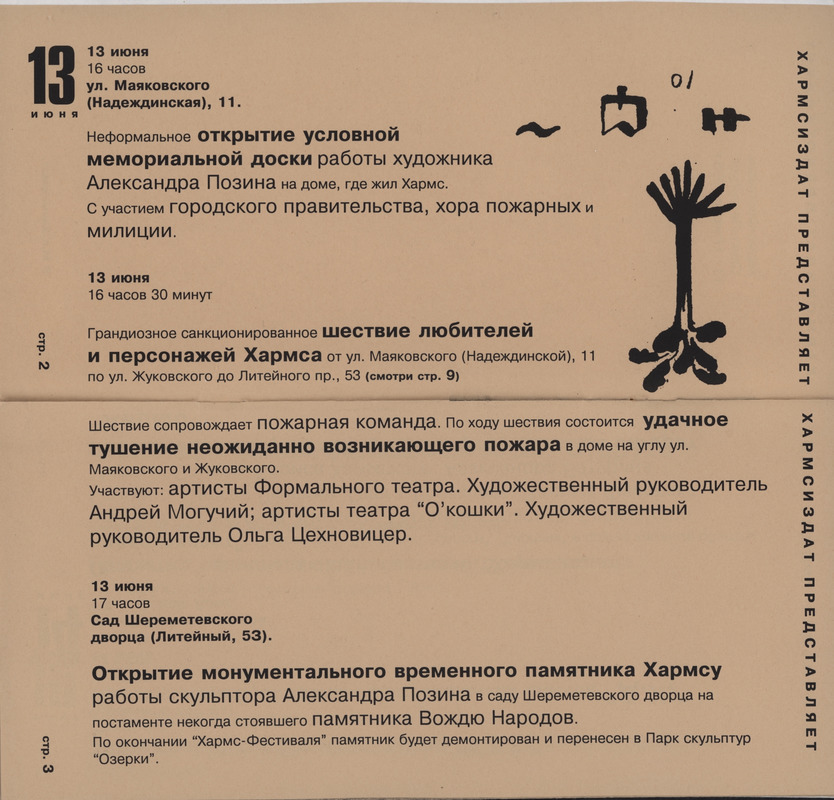

Nevertheless, the mood of the Kharms Festival was created by the performative program, which turned it into an eccentric, crowded event that overtook not only the museum but also the city. During the four days of the festival, experimental theater performances, film screenings, and musical events were held in the garden of the Fountain House. The largest event, organized by Gleb Yershov, took place on the opening day. Kharms’ house was located far from the Anna Akhmatova Museum, at Mayakovsky Street, 11 (formerly Nadezhdenskaya Street), and it was there that he was arrested in 1941. The building was destroyed and a new one built in its place, which features unofficial graffiti with a portrait of the writer and an official memorial plaque. In 1995, there were not yet any signs of the memory of Kharms in this area of St. Petersburg.

At first, there was an idea to install a temporary memorial plaque and hold a festive procession of Kharms characters from the house to the Anna Akhmatova Museum and Apartment. Gleb Yershov recalls that events developed rapidly. To begin with, he tried to find a theater director who was not afraid to work on the street. On the advice of friends he approached Andrey Moguchy (now head of the Bolshoi Drama Theater, and then the organizer of the small, independent Formal Theater), who agreed to take part in the festival together with his troupe. In addition to the scenes in the urban space, Moguchy offered to arrange a spectacular incident that would attract casual viewers, such as a fire.

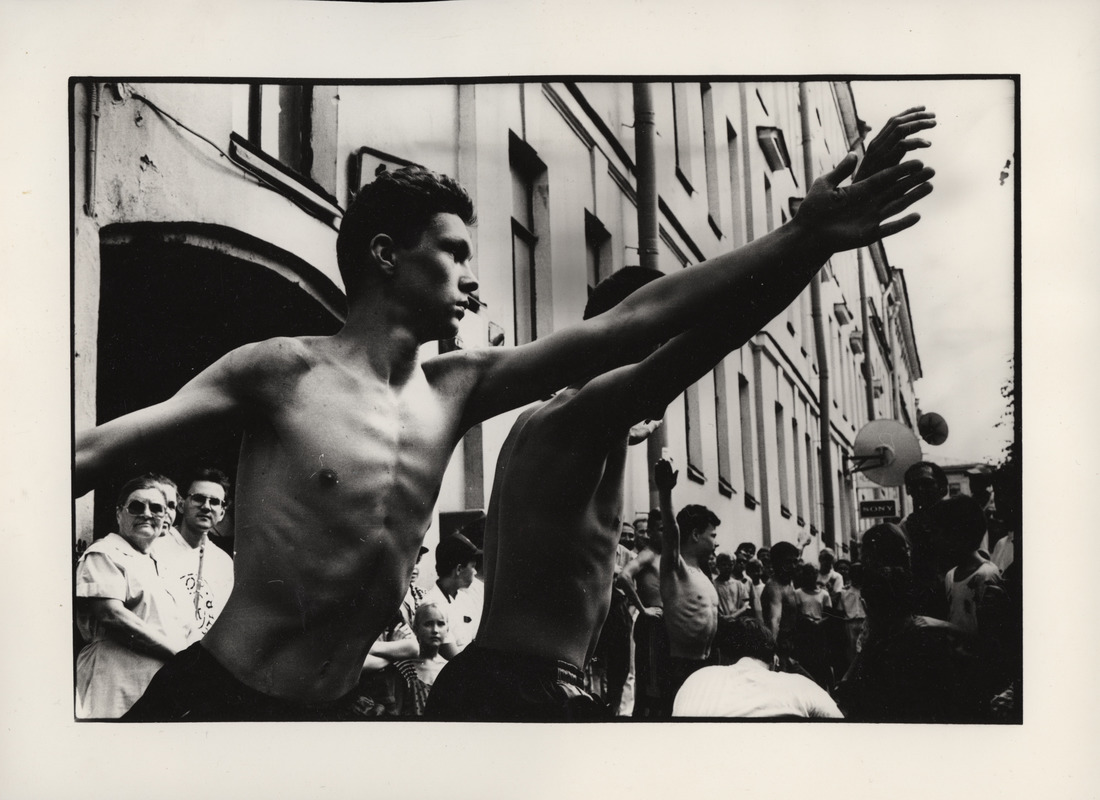

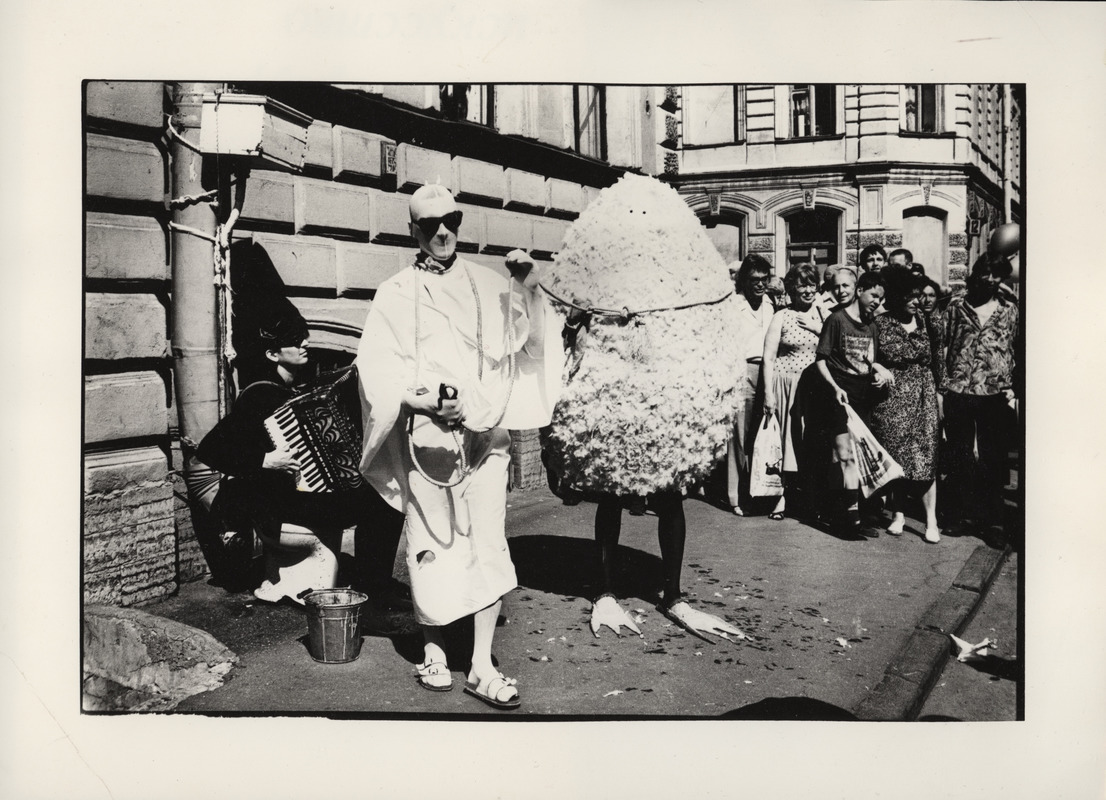

A large-scale event, for which it was necessary to block traffic, required permission from the local police. It was received, and at the appointed time several cars with law enforcement officers appeared, blocking the streets. Then the actions occurred one after another. Solemnly, to the poetry of Kharms, a temporary memorial plaque was revealed, made of rusty iron by the sculptor Alexander Pozin. From the courtyard of the house, the first characters began to appear: musicians and Death, played by dancer Nina Gasteva. They shouted “Fire!” into a loudhailer they had borrowed from the police. Black smoke rose from a house at a nearby intersection. This building, which was due for major repairs, was empty, but during the festival it was populated by the artists Dmitry Pilikin and Kirill Shuvalov, who turned it into a total installation, placing in the windows everyday things left by former residents, such as clothes, furniture, and sanitary ware. The fire was staged thanks to smoke bombs acquired from the Lenfilm studio. The firefighters did not come. They had been warned that this was a staged event, and instead of them Roman Trakhtenberg, who was then director of the Moguchy Theater, drove around with a barrel of water on a cart pulled by a horse.

When the spectators and bystanders, attracted by the noise and smoke, approached the house, they saw people fearlessly jumping out of the windows, apparently in memory of Kharms’ falling old women. This piece was performed by the actors of the Formal Theater. Many years later, Moguchy recalled the Kharms Festival as the first immersive performance in his practice, although by 1995 he already had experience of street performances and had made several productions involving audience interaction. Anyone, from local homeless people to taxi drivers, could become a spectator and a participant in the show.

From the house, the motley crew moved toward the museum. The Formal Theater actors were joined by athletes who built a pyramid. There were invited students from one of the schools, a person in a feathered egg costume dressed by artist Alexey Kostroma, and a dog man being walked on a leash, performed by artist Kirill Miller. As artist Olga Egorova (Tsaplya) wrote in a newspaper notice about the event, “and it was strange. . . something happened to the world: it seemed that every dog on the planet had turned into Kharms’ dachshund, every mustache in the world had turned into the drunken mustache of a janitor, the police into mounted police, and the firemen into his firemen. "

The Kharms Festival took place another four times, and each iteration included a performative program that allowed visitors to see academic debates or the process of museum archiving as events that can be turned into something unpredictable in a Kharmsian way. Today, the memory of such events is interesting not only because of the history of the study of the avant-garde but also as an example of a completely different type of regulation of the public space. In the 1990s, it was much easier than it is today to turn the city into a platform for absurd artistic gestures that violate routine order. It did not require a large budget, and a young curator with little experience of bureaucratic procedures could get all the permits.

The project Art in the City: The History and Contemporary Practices of St. Petersburg Performance was developed by Anastasia Kotyleva and Maria Udovychenko for the podcast of the same name presented on the Museum’s booth at the 9th Cosmoscow International Contemporary Art Fair.