Go there, God knows where, fetch me what God knows I want

In a lecture at Leningrad State University in the early 1980s, art historian Ivan Chechot illustrated the increasing interest in history using a famous story about Michelangelo. In 1496, following the advice of one of the Medici, the artist intentionally aged his statue of Sleeping Cupid (now lost) by burying it to make it look “antique,” and then sold it to Cardinal Riario in Rome. Today, when even the existence is in question, when for more than twenty years there have been no significant developments and no artistic mainstream exists, the collecting and archiving of cultural heritage is a real challenge. As art historian Ekaterina Andreeva wittily remarked, contemporary art aspires to be “everything,” while meaningfully pointing out its own “nothingness.”[2] So what do we archive and how?

There are many examples of archiving as art and art as archiving. Numerous artists produce objects and installations that look like an array of old archives or even pure garbage. In the West, Christian Boltanski’s work is a vivid example of how artists redesign old objects into works of art. Among Russian artists, Ilya Kabakov aestheticizes the mental and physical residue of Soviet communal lifestyle.

St. Petersburg has its own tradition of artistic archiving, developed by the St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art (PAiBNI), which I founded in 1999 at Pushkinskaya 10 art center. This tradition unconsciously harks back to the profound roots of the Orthodox mentality. Unlike Boltanski’s ideologically sterile physical remains and Kabakov’s fake garbage, this is about “energy resources” of a completely different kind. They are not a substitute or mockery, nor are they statistics, demonstrations or post-structural manipulations. Now that art is no longer a conventional truth but just a range of wishes and hopes—process but not result—it returns to archaic models, and its archiving becomes the attainment of Divine grace and the collection of evidence of miracles. This tradition can be traced back to John Moschus, a Byzantine writer of the late 6th–early 7th centuries. While travelling through Orthodox territories immediately before the early Muslim conquests, he collected testimonials of the life and miracles of Christian men of faith in The Spiritual Meadow.

The policy of the St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art was based on the ideas about energy, immortality, and the noosphere developed in Russia by Nikolai Fedorov (1829–1903), Vladimir Bekhterev (1857–1927), Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945), Alexander Bogdanov (1873–1928), and Lev Gumilev (1912–1992). The increasing popular interest in Fedorov’s ideas in Russia [RA4] is shown by the unprecedented success of Igor Miretsky’s sci-fi novel about the philosopher, The Archivist (2019), and the exhibition Philosophy of Common Cause at Cosmoscow Art Fair in 2019.

A Bolshevik, visionary, and natural scientist and the founder of tektology, which anticipated cybernetics, Alexander Bogdanov was criticized by his close friend, Vladimir Lenin, in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1909) for considering the world (in line with scientific developments of the time) to be a balance of energies. In his 1916 speech “Human Immortality from the Scientific Point of View,” Vladimir Bekhterev stated that “all energy must be acknowledged as a single essence existing in the universe” and it “serves as the origin of both the material and spiritual worlds.”[3] Later he noted that “not one sigh, not one smile ever disappears without trace.” Bekhterev suggested that energy is transmitted through communication from one human being to another. The academician Vladimir Vernadsky, who wrote a letter to Stalin explaining World War Two as part of a geological process, went further, saying that even solitary actions, thoughts, and dreams were part of the noosphere. The noosphere is the sphere of human culture, a new stage in the development of Earth’s geo- and biospheres. Therefore, by establishing museums and archives we enhance our ability to envision and observe phenomena, objects, and energies that connect us to the “database” and energy sources of our planet and the Cosmos.

My personal archive experience began in the mid-1990s,[4] when I felt that contemporary art and modern humans were losing substance. The focus had shifted from art to creativity. Creativity is not limited by time or space. It is a state of exaltation that blends into everyday life and is “conserved” (museified, archived, represented) by art (here the Greek word techne/τέχνη is important, which is often translated as “art”). I began to see art as communication, which is linked to the words “common” and “communal.” In 1995 I started “collecting” the art of communication by filming my meetings with significant local artists and celebrities, eccentrics, and originals. I aimed to capture “miraculous moments.”[5] In essence, a miracle is your own state, the tuning of your attention, and you never know where it will appear. I was surprised and happy when, that same year, my project, comprising several lines about my plan to live in Berlin and document everyday communication with people I was interested in led to a residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien and a grant from Philip Morris Kunstförderung. The result was hours of recordings of meetings with people from Russia and Europe, which I tried to categorize by personality type and survival strategy: freaks and beasts, geniuses and saints, magicians and scientists. This work led to an exhibition. Along with numerous tapes there was a confessional, a shower unit, a phone box, a barber’s chair, etc.

There was no art object, no author, no viewer, and the “work” (state of mind) was created with those present in the space and sometimes transformed into dances. But the ontological concept of the project failed. I understood that video cannot capture the energy of an event, and the exaggerated role of communication and interaction[6] betrays an energy crisis in the so-called civilized world. We create more and more artificial devices and substitutes to communicate and capture the process, but this communication feels more like the rapture of vital energy and its fixation is shallow, like text messages compared to letters and diaries, which are long forgotten by artists. Documented facts are an important challenge for the history of contemporary art. which in Russia is reduced to the repetition of anecdotes and koans, a throwback to Vasari’s art history.

***

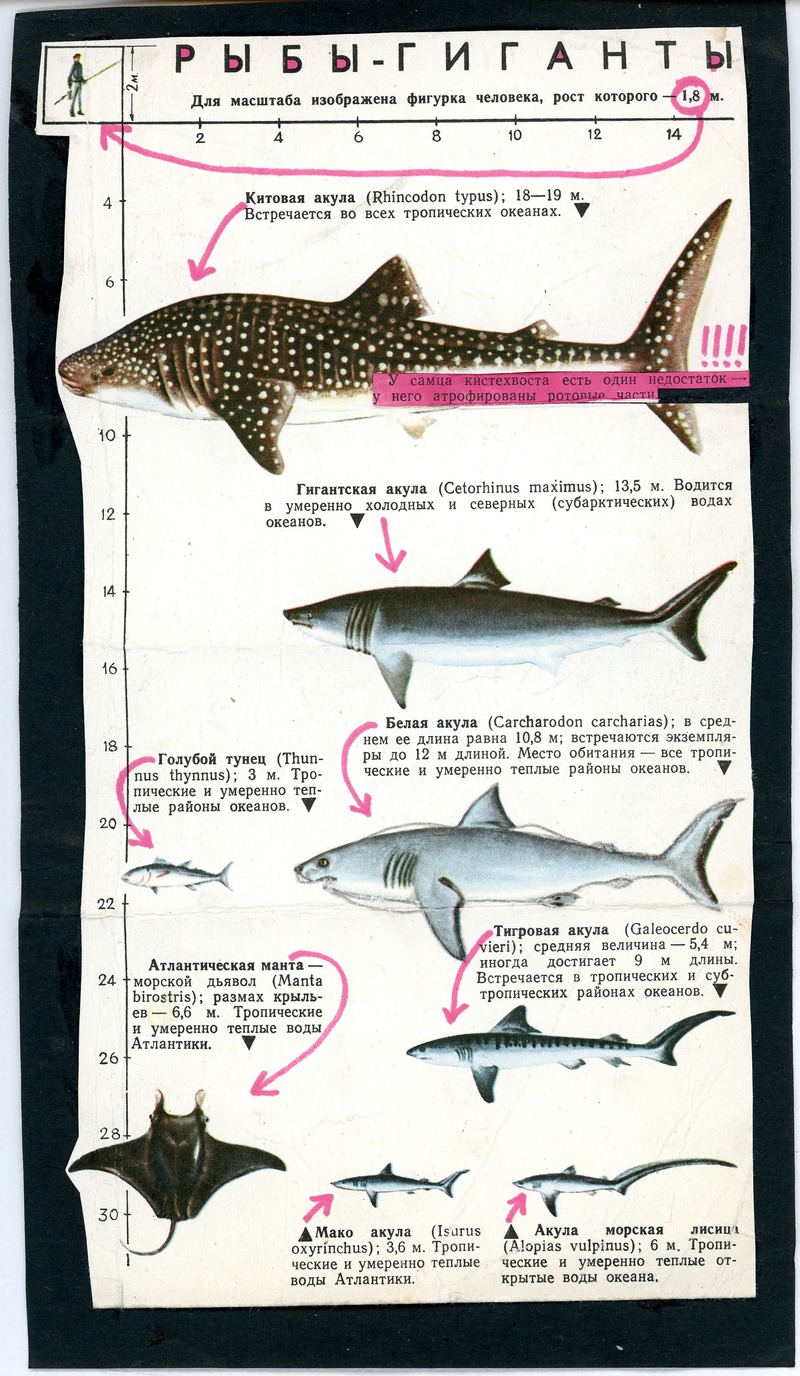

As a child, when I participated in archeological digs with my parents, I learnt that the most precious finds were hidden beyond settlement walls, in ditches and on dumps. The futurists, the first media artists, transcended the boundaries of art by making anthropological trash part of the deal. Artists Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) and Ilya Zdanevich (1894–1975) were the first to exhibit street signs. They coined the term “everythingism,” which underlined that the whole world is material for art. In the 1960s and 1970s in Leningrad/St. Petersburg, this narrative was further developed by Valery Cherkasov (1946–1984) and Boris Koshelokhov (b. 1942) and actively promoted by Timur Novikov (1958–2002) and other members of the New Artists group that he founded in the early 1980s: Oleg Kotelnikov (b. 1958), Vadim Ovchinnikov (1951–1996), and Kirill Khazanovich (1963–1990). Comprehensive study of this tradition confirmed my idea that it is necessary to revisit conventional versions of the history of Russian art.[7]

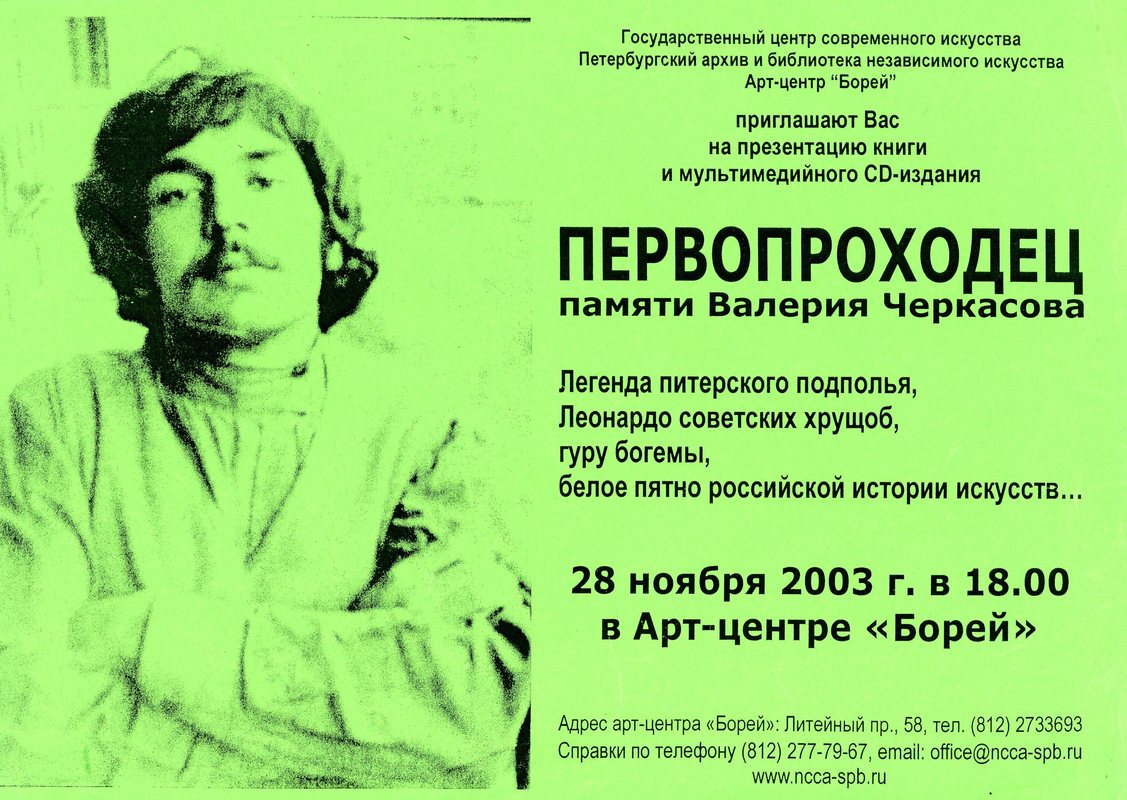

Valery Cherkasov created assemblages out of improvised materials, sometimes presenting garbage installations at rubbish dumps. He was a rather eccentric person. One might recall the suicide attempt when he fell on two carefully placed lancets aimed at his eyes, or his hiking trips to Finland when he was stopped by the KGB at the border and placed in an asylum. He transformed his apartment into the Plushkin Museum,[8] named after the character in Gogol’s Dead Souls who hoarded meaningless stuff. From matches to cigarette boxes, all the objects in Cherkasov’s home were treated as art and arranged in elaborate compositions. At first, one could move around the improvised museum using a path made of stools, but then the display grew to the ceiling and visitors could only squeeze into the corridor and talk to the invisible host hidden somewhere in his nest in the center of the composition. After Cherkasov’s mysterious death, his collection returned to the dump, as his heirs could not conceive that what they inherited was art.

One of Boris Koshelokhov’s motto was: ‘We paint our souls with whatever we have, on whatever we find!’ He began making paintings only after producing “concepts,” including the assemblage Longing for Nevsky Prospekt, a composition made from underpants, a tablecloth, a mirror, a crucifix, and other objects found during a walk on Leningrad’s main street in 1976. Koshelokhov was one of the few teachers of the New Artists, who practiced a multidisciplinary approach without differentiating between genres and mediums. The same person could be a painter, a musician, a fashion designer, and a poet, since the main thing was a “sublime state” and constant artistic exaltation.

While Western artists, creative industry works, and graduates of the Academy of Arts did not understand the connection between art and life, and the Moscow conceptualists produced what one of them called ethnographic reports sent out to the West from the exotic Soviet wilderness, the New Artists were something different. Soviet underground artists did not have the opportunity to exhibit and sell their works, often refusing to as a matter of principle. Richard Vasmi (1929–1998) stated: “An exhibition is a reason for some to feel proud, but I would be ashamed.” They made art because they did not want to do anything else, often, like Cherkasov, without even thinking of a name for their activity. It was the “art of pure necessity,” in which experience and efficiency were more important than symbolic denomination. This approach was due to the need to survive: to become and stay true to oneself, demanding a precise, minimalistic gesture that was spectacular and admirable.

Collecting testimonials about these states required the same openness, audacity, and unorthodox thinking. As well as archiving, St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art immediately became home to exhibition and research activity. In a tiny room, barely bigger that Rodion Raskolnikov’s closet, exhibitions opened every month without any financial support. The collection developed thanks to special deals like Books and Papers in Exchange for Beer, which resonated with the artists. Often people brought large boxes garbage which contained treasures. The PAiBNI Herald and the journals Susanin (susanin.zarazum.ru)—a satirical look at St. Petersburg artistic life—and Genius were published by the archive. Many Russian and international students and researchers orked in the St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art.

I mainly collected materials of the period I was the most familiar with, the 1980s and 1990s. It was one of the most exciting times in the development of contemporary Russian culture. The dynamics of change and the intensity of life during perestroika were similar to the processes described by the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their fundamental work Capitalism and Schizophrenia. The disruption of Soviet language and culture, the death of ideology, the revealing of the void, euphoria, semiotic catastrophe, total identity crisis, anarchy, and panic finally shaped, in the late 1990s, a new ideology of greed. After the mischievousness and journeys of the perestroika period came the crisis. The new ideology broke people just like the old one did, the myths about the Western art market and creative Eden collapsed. Perestroika was our belated initiation. It left us with nostalgia for times of change, but also inspired a need to reassemble a world in pieces to counter new spiritual substitutes. Archiving at PAiBNI was not about creating a new ideology, narrative or text, but “reassembling the world” through focus on intonations, textures, and new vital feelings. Members of the archive were not so much interested in traditional art objects, such as paintings, as in marginal objects—waste products, physical remains, smells (with old clothes of underground artists being a repository). There was even an idea to ensure continuity in case of the death of the Russian art by setting up a sperm bank at Pushkinskaya 10. This idea was abandoned due to the high price of equipment. Research and exhibitions highlighted phenomena, groups, and individuals which were little known and unappreciated or completely forgotten.

The most interesting trends in collecting and museology of recent decades relate to increasingly dynamic change in our perception of “objective knowledge.” Simultaneously, contemporary science is becoming more specific, so that scientists from closely related areas of knowledge within the same discipline have a hard time understanding each other, and sci-fi writers cannot keep pace with the latest discoveries. As a result, science fiction gives way to fairytale fantasy. This aesthetic, both showing previously unavailable objects and mixing up “sets” of images in unprecedented combinations, produces the Instagram effect: information become more global, involving millions of people worldwide and is also increasingly fragmented and detailed. On social media we see the rise of informal communities oscillating between science, art, ethnography, collection, and esotericism, where members share information and the intricacies of the field (the @the_wunderkammer_society Instagram account). Oddities and curiosities are popular on the Internet. Yet collecting these objects led to the creation of the first museums, including the first museum in Russia, the Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg. Now we see collections of curiosities in a virtual space where the basic human interest in gathering and admiring things, plus empathy and learning, is developed using the latest technology. This is the triumph of phenomena that in the 1980s were referred to as “the return of materiality,” “technology in everyday life,” and “the sociology of technology,” the study of the sociology of things, where there is almost no difference between the language of cyberpunk and science.

***

In 2007, St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art was closed by the administration of Pushkinskaya 10 for “lack of seriousness.” The archive had to move all of the objects seen as garbage by the nonconformists, such as artists’ clothes. The premises were to be used for a “real” archive, with documents, such as artists’ petitions to the Soviet government and correspondence with the Culture Department, but the space was then let to a publisher. What’s going on? Why do veterans of the battle for the freedom of art repress experimental creativity?

From 1989 to 1998 Pushkinskaya 10 was the most important art squat in Russia. After 1998 an agreement was reached with city officials and part of the renovated building was given to artists on a long-term lease. It is thanks mainly to the artist-administrators who appeared in the underground in the early 1980s that the artistic community survived this battle. To counter the official narrative, they started developing alternative structures that mirrored public ones. Their ideology—art as a weapon for social justice—copied the governmental discourse but gave it the opposite meaning. Every artist who did not fit into the pro-government mono-discourse, from abstractionists to salon painters, was embraced by the nonconformist community, as long as they were “on this side of the barricade.” Young, new wave art was opposed by the nonconformists no less violently than by the official art community. Bearded political preachers, who considered themselves good artists just because they took the right political positions, saw 1980s new wave art and behavior as disruptive and anti-artistic. By winning this battle and taking power on their own territory, the nonconformists stopped being political activists and in turn became the leviathan. It’s understandable: anyone would like to grow old quietly with a cheap studio in the center of the city. The “nonconformists” aimed to conserve and strengthen the vertical power system what matched what was happening in Russia. The fun-filled, apolitical archive which was like a nightclub with its music, dances, provocations, and interest in youth culture, was an ontological reference to “the image of the enemy.” No wonder that this center of anarchy, promoting the complexity of a structure tending toward simplification, was destroyed by this structure. One should also remember that the local independent culture of “unappreciated geniuses” tended to oppose self-reflection, labelled it “being clever.”

St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art was probably founded too early, and its activity did not extend to its young audience. Real interest in the 1980s and 1990s only appeared in the 2010s. Nevertheless, the archive helped to conserve the heritage and spirit of the time of change, support traditions, and develop the self-awareness of St. Petersburg’s art.

P.S. Immediately after the closure, the archive materials were shipped to the exhibition THE RAW, THE COOKED AND THE PACKAGED — The Archive of Perestroika Art at Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki.

From fall 2000 to spring 2007, St. Petersburg Archive and Library of Independent Art organized 88 exhibitions, including 75 exhibitions on its own premises. Below is a description of some of the most important projects in chronological order.

2000

The archive began its exhibition activities with the first St. Petersburg exhibition of mail art, Vadim Ovchinnikov’s Mail Art. The shaman, guru of the St. Petersburg art community, genius painter, writer, and musician was presented from an unfamiliar perspective, known only to his close friends. More than 100 items of mail art were displayed.

Samizdat Forever (with Navicula Artis Gallery) presented the archive’s specific field of expertise and was a unique event. The corridor where the archive was located was used for an exhibition of materials on the history of samizdat. As well as traditional samizdat—underground magazines and reprints of Carlos Castaneda, John C. Lilly, and Mikhail Bulgakov—the exhibition included handmade leaflets and posters.

Е-Е. A Restrospective of the 1980s Photos of Evgeny Kozlov (Berlin) looked at the fashion of the early 1980s. There were brilliant photos of events such as the first twist parties and concerts by Sergey Kuryokhin’s group Pop Mekhanika and Kino presented in the form of hundreds of index prints artistically processed by Kozlov.

Everybody get something… (Contemporary Japanese Culture According to Oleg Kotelnikov) was a collection of works of art and artefacts brought from Japan by one of the most revered leaders of “wild” art. John Lennon’s lyrics ironically referred to Kotelnikov’s Japanese wife.

A Tribute to Valery Cherkassov (1946–1984) was organized together with Timur Novikov. The exhibition reintroduced Cherkassov to art history. His previous (posthumous) exhibition had been organized by Timur Novikov in 1984 in the Assa squat gallery.

Exchange. Andy Warhol and the New Academy of Every Kind of Art exhibited gifts, documents, and photos from the Museum of the New Academy of Fine Arts. The display included Campbell’s soup cans and posters signed by Andy Warhol and presented to the Leningrad artists during Joanna Stingray’s visit to the city in exchange for works they had sent him, as well as photos of the king of the pop art holding these works.

Evgeny Rukhin. Photographic Archive of the Artist from the Collection of the US Consul-General Paul R. Smith. The exhibition displayed the secret card index of the leader of the Leningrad nonconformist artists of the 1970s, who died in a fire in unexplained circumstances. Printed on expensive glossy paper, these folded booklets with the artist’s address and black-and-white photo inserts of his works are living proof that, contrary to public opinion, Rukhin had a well-developed market and did not care about KGB surveillance.

Kirill Shuvalov’s exhibition Cargo 2000 consisted of numerous small lead boxes. It was a morbid comment on the war in the Caucasus, from where dead soldiers were sent home in lead coffins with the inscription “Cargo 200.” It was also an ironic remark on the archive’s declared “new methods of archiving.”

2001

My Past and Thoughts: From the Leningrad Art Historians’ Club to the Institute of the History of the Contemporary Art included documents, manuscripts, photos, letters, conference programs, and other documents about the history of independent professional art criticism in the Soviet Union. Leningrad Art Historians’ Club was founded in 1995 by graduates of the Art History Department of Leningrad State University, most of whom were students of Ivan Chechot.

History of Leningrad / St. Petersburg Independent Art through Posters from the archive collection. Handmade posters and invitations to apartment exhibitions were exceptionally interesting. The display did not fit the space, even with salon-style hanging, and the exhibition was shown in two parts.

Historical Costumes of St. Petersburg Artists of the late 20th Century from the archive collection was also conceived in two parts and was subtitled Artists’ Smells. The display included various details of the dressing habits of prominent artists and musicians from the 1950 to the 1990s.

The exhibition of Marina Alekseeva’s objects, Inside Rooms, consisted of small “stage boxes” with miniature models of the churches of the major religious traditions and denominations and spaces with various functions. Like in the children’s game sekretiki (little secrets), archiving meant “the development of secure, hidden places where elements once impetuous and distraught find peace and rest like doll-mummies where they can be seen and cherished.”

An exhibition on the popular contemporary art guide Susanin was organized as part of the Art Media Forum. This A3 newspaper, with its satirical attacks on the art world, regardless of personal status and authority, was considered by many to be the best art journal, occupying a meta-position in local culture.

Our Kovalsky was a parody of the personality cult surrounding the main administrator of Pushkinskaya 10, Sergei Kovalsky, the omnipotent master of the former squat.

History of Gallery 21 in Photos profiled one of the most remarkable non-profit galleries at Pushkinskaya 10, which saw the birth of new media art and cyberfeminism.

The Exhibition on Bronnitskaya Street, 1981 presented archive materials about an underground exhibition successfully organized on the KGB’s doorstep, which shaped alternative underground structures.

Abstractionism in Russian Caricatures of the 20th Century was organized in cooperation with the New Academy of Fine Arts and accompanied by a handmade catalogue.

2002

Object Abstractionism was a solo exhibition by Vadim Voinov, who during the Soviet period worked on the Government Committee for Historical and Cultural Heritage Management, which was responsible for renovation of urban housing. Using objects found in the ruins, Voinov created his “functiocollages.”

The exhibition Artists and the Samizdat of the 1970s–1980s presented Soviet samizdat from the aesthetic and artistic point of view for the first time.

Leni Riefenstahl During the Shooting of Olympia, August 1936 was a reaction to Riefenstahl’s visit to St. Petersburg. The display included photos, autographs, and a video recording of an interview.

The Japanese Week Festival, organized by Oleg Kotelnikov, was held every year. Wind from the Slopes of Fuji presented landscape in the art of Japanese painted postcards of the early twentieth century.

Autographs of Cultural Figures of the 20th Century presented autographs of Derrida, Rasputin, Nam June Paik, John Cage, and others from private collections.

Timur Novikov in Photos, with works from the archive and private collections, was a reaction to the death of this leading figure of the St. Petersburg art scene.

The archival exhibition STUBNITZ – Art Ship told the story of the “artists’ ship” that visited St. Petersburg in 1994, marking the birth of techno-art in Russia.

2003

Malevich Passion was an exhibition of paintings and drawings from the 1950s through the 1970s by underground artists with a keen interest in suprematism.

The annual Japanese Week exhibition Suicidal People introduced the suicide cult in contemporary Japan and presented traditional seppuku tools.

The book exhibition Against Abstractionism and Formalism – In Favor of Realism explored critics of modernism in Soviet publishing as a source of education for underground artists. The display included popular and rare books from the 1930 to the 1980s from the archives and private collections.

Squat Life: Club NCH/VCH (1986–1996) in Photos and Archivespresented for the first time the earliest and largest young people’s art squat.

Svin and Yufa: Stupid Years of the Russian Punk was the first ever research into the origins of punk in Russia. It was popular with veterans of the movement and novices. The main characters in the exhibition were Svin (Andrei Panov), the founder of the first punk collective Automated Satisfiers, and Yufa (Evgeny Yufit), an artist and cinematographer, leader of the necrorealism movement.

Cyberfeminists in Altai was the story of a risky trip by Alla Mitrofanova and Irina Aktuganova with three kids to the land of shamans and Scythian burial mounds, including bungee jumping, visits to sanctuaries, horse riding, and numerous adventures.

A Reconstruction of the Exhibition Collage at 103 Gallery, 1992 (from the History of the Pushkinskaya 10 cycle) presented a complete reconstruction of the exhibition from the golden age of the Pushkinskaya 10 squat.

2004

The archival exhibition Walls, Floor, and Ceiling of the New Academy of Fine Arts examined the various activities of the Academy. Exhibits included unique “wallpaper” from the corridor of the New Academy created by Timur Novikov using a collage of journals and magazines. There were also parts of the floor and the molding, as well as all kinds of garbage from the “old” New Academy.

Fathers and Sons showed works by several St. Petersburg artistic dynasties, encompassing up to five generations: from pre-revolutionary art through socialist realism and the “avant-garde” underground to contemporary children’s drawings.

An exhibition about the flag of the art center Pushkinskaya 10 displayed dozens of everyday objects, garments, and art works covered with the famous toadstool pattern. In 1996, I suggested a new national flag with white spots on a red background, and it was adopted as the new flag of the art center.

Oleg and Victor’s Accessories and Fetishes showed the sophisticated props that the neo-academic duo of Victor Kuznetsov and Oleg Maslov use for their paintings (lyres made of toilet lids, codpieces, armor, tunics, wreaths, etc.)

2005

The exhibition Gennady Orlov, Music Addict featured clippings and photos from the 1980s and 1990s of the Russian rock stars Boris Grebenschikov, Konstantin Kinchev, Yury Shevchuk, Viktor Tsoi, Vyacheslav Butusov, Egor Letov, Mikhail Borzykin, Oleg Garkusha, and others. Reel-to-reel recorders played dance music and the exhibition included rare vinyl and handmade tapes.

Tatyana Barti’s exhibition Who Lives in a Small House?presented caricatures of the inhabitants of the Pushkinskaya 10.

The T-shirt as an Artefact of Contemporary Art showed handmade garments from the archive, the New Academy of Fine Arts, and private collections, which conveyed the aspiration to look fashionable in spite of Soviet monotony.

Rave Spacemen. The Early Years of the St. Petersburg Techno Culture was organized together with Konstantin Mitenev and showed numerous flyers illustrating the history of the club and rave scenes in the Soviet Union.

2006

Designs for Christmas Trees involved professional and amateur artists. It was repeated in the Marble Palace of the State Russian Museum together with professional design studios.

Popular Conceptualism exhibited late-twentieth-century Soviet handmade items of home décor from private collections and reproductions of similar art works produced by renowned contemporary artists. The display included chests covered with magazine clippings, a tradition which extended to toilet doors, cupboards, driver cabins, and musical instruments. The exhibition was centered around a toilet door from Ivetta Pomerantseva’s flat, covered with Soviet alcohol labels from the 1960s and1970s by her father and her grandfather.

The memorial exhibition in honor of Vadim Ovchinnikov, What Kills Us, showed versions of one of the artist’s works produced by his friends.

Sketch Pad traced the evolution of sketch pad design from the 1950s to the 2000s, with objects from the archive and private collections.

Runes of Happiness. Military Psychedelic Romanticism of the 1980s and 1990s by the groups Voennoe Ministerstvo [War Ministry] and Chapaev displayed for the first time the work of forgotten artist groups with an interest in military history, esotericism, and conspiracy theories.

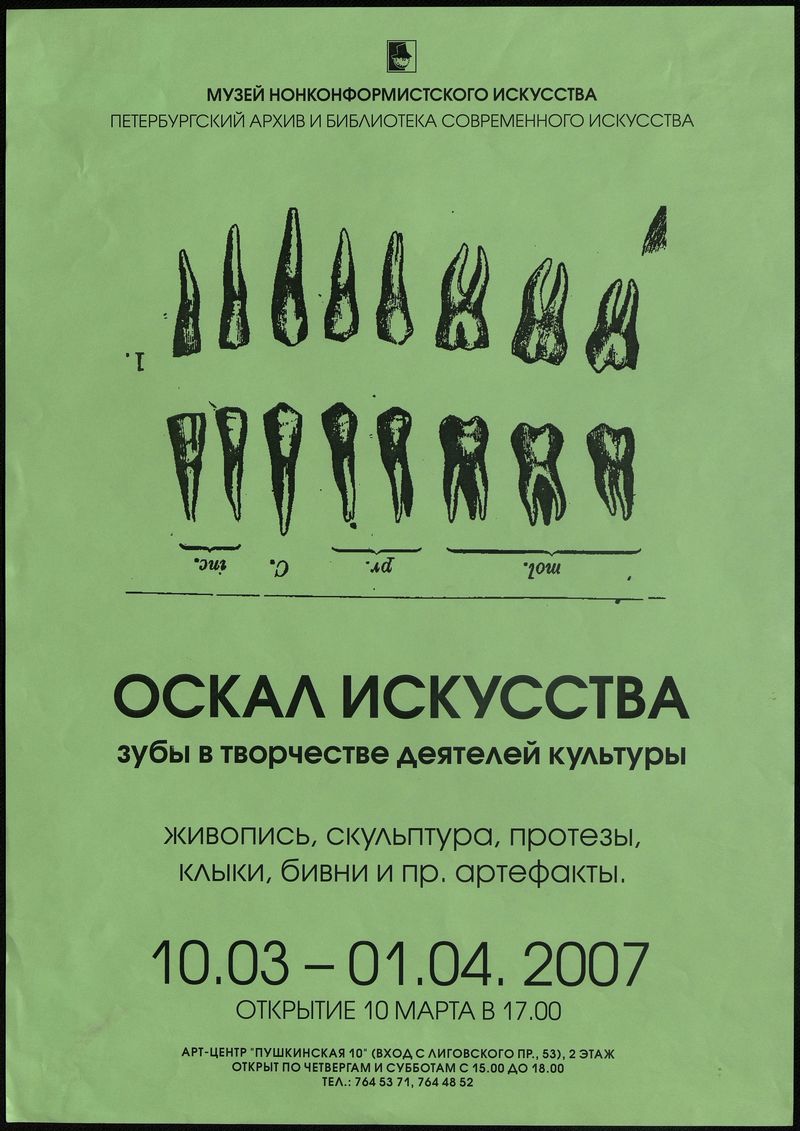

2007

Children’s Conceptualism presented works by children from St. Petersburg and was an ironic commentary on the absence of new ideas in contemporary art. The exhibition included phone video recordings of children fighting in school toilets, hand-made bombs, ballpoint pen letters on birchbark, and other artefacts created by children, which often reflect manias of the adult world.

Art Grin. Teeth in Creative Imagery reflected a traumatic subject for St. Petersburg artists. The exhibition included contemporary art works, artists’ teeth, dinosaur (60 m. years old) and bear (30,000 years old) teeth, plus dental instruments, wax models, a piece of bread from the Kavkaz restaurant with the marks of Robert Rauschenberg’s teeth (1989), etc.

St. Petersburg Penguinism showed the incredible popularity of these birds in St. Petersburg art, displaying hundreds of works of art, taxidermy figures, statues, toys, objects, and films.

[1] The first version of this text was based on a lecture delivered at the 7th Annual Aleksanteri Conference, Revisiting Perestroika, at Helsinki University (2007) and subsequently published in the Framework Review. The Finnish Art Review, 8, April 2008.

[2] Ekaterina Andreeva, Vse i Nichto: Simvolicheskie figury v iskusstve vtoroi poloviny XX veka (St. Petersburg: Izdatelstvo Ivana Limbakha, 2004).

[3] Vladimir Bekhterev, “Immortality from the Scientific Point of View,” Society, 43, 2006, 74–80.

[4] Before that worked in various St. Petersburg museums and the Hermitage Academic Library.

[5] Gilles Deleuze would have called then “Events.”

[6] Curiously, the early 1990s was a time of the triumphant rise of reality shows, whereas their origins are usually traced to the late 1940s.

[7] In 1988, Alla Mitrofanova and I published the article “The Russian Sense of Shape in Art of the 18th to the 20th Century” in the twentieth issue of the samizdat magazine Mitin Zhurnal,. We emphasized the fact that Russia did not shape secular forms in Western art and only adopted them as a mature form in the eighteenth century. This fact is evident but often overlooked. In Russian art, spiritual beauty (or ideology) was often considered more important than materialistic beauty. It hides visible discontinuity and historical contradictions, yet requires the setting up of new hierarchies and accents, which differ from the conventions of the Western history of art.

[8] Remarkably, Plushkin is also a character of one of Ilya Kabakov’s important texts (see “Nozdrev i Plushkin,” A–Ya, 7, 1986), and Kabakov later began to create spatial installations reminiscent of Cherkassov’s “museum.”