In late 1975 or early 1976, the three of us Nikita Alexeev, Lev Rubinstein, and me were at Irina Nakhova apartment on Malaya Gruzinskaya Street in Moscow, sitting and talking about how good it would be to create a magazine on unofficial art. It was during this conversation that the name for such a magazine was first mentioned. I don't remember who, but one of us said the word archive of new art. I think it was Rubinstein, as at the time he was involved with some sort of archive. On that day we didnt take it anyway further, other than coming up with that name: the Moscow Archive of New Art (MANI).

Collective Actions first started its activity in March 1976. By the end of 1980, I completed the first volume of Trips Out of Town, which comprised documentation of the group's actions. I collected materials and developed a structure that included extensive descriptions and firsthand accounts of those who were involved, made a list of artists, wrote a foreword, etc. I was a kind of accountant, as I wasn't just an editor, but a publisher and printer as well. I printed the texts for all four volumes, Nikolai Panitkov bound the four books that were produced, and I glued the photographs into them.

After the first volume of Trips I still felt an itch. It was an interesting experience, and I remembered MANI, the Moscow Archive of New Art. I started discussing a possible form for the publication with Ilya Kabakov and Nikita Alexeev.

Andrei Monastyrsky

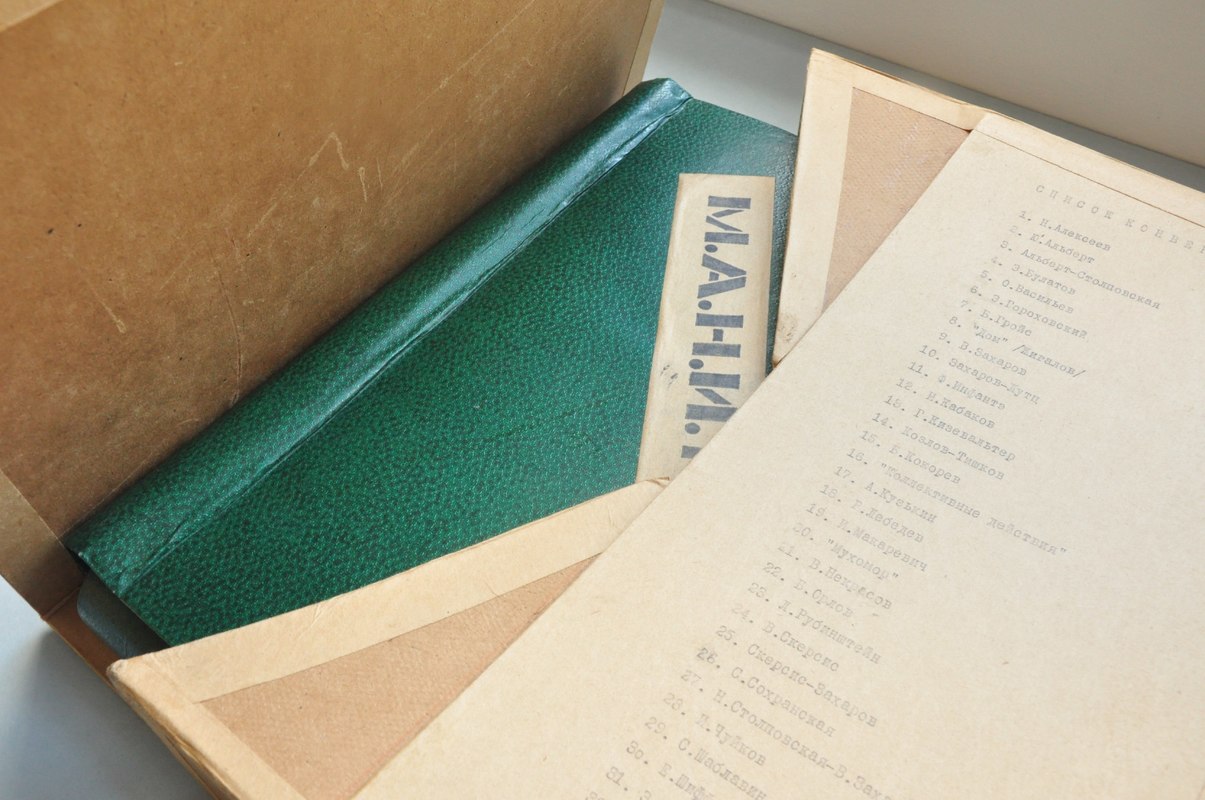

After the first volume of Trips I still felt an itch. It was an interesting experience, and I remembered MANI, the Moscow Archive of New Art. I started discussing a possible form for the publication with Ilya Kabakov and Nikita Alexeev. As the name contained the word archive we were open to doing something other than an ordinary magazine. Then it became clear that MANI should also comrpise four volumes, like Trips Out of Town. Finally, we decided that MANI should be a folder. Maybe Panitkov suggested it, or maybe me, or Kabakov or Nikita. I don't remember now. Anyway, MANI had a format and this format was a folder.

I began putting together a list of those, who would go into the folder. I did this on my own just because I liked this work and no one else wanted to do it: everyone was busy with their own things. I was very strict in my choice of participants. I only picked those I liked, and that is why there are very few artists in the first MANI folder. I chose a theme that interested me: those artists who worked mostly with text (although there were also some photographs). I agreed with the artistsóIlya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, Oleg Vassiliev, and Ivan Chuikovóthat they would select works for the volume and asked them to let me have a small amount of money for photography. George Kiesewalter played an important technical role: photographing, developing, and printing. After I had everything ready, Panitkov made a beautiful case in which I placed all of the envelopes containing texts and photographs.

I was criticized for my discriminating approach and voluntarism, for excluding too many artists. The next folder, which was made by Vadim Zakharov and Viktor Skersis, included over forty people. Skersis and Zakharov didnít only expand the list, but selected an easier format: the case was replaced by a regular cardboard folder.

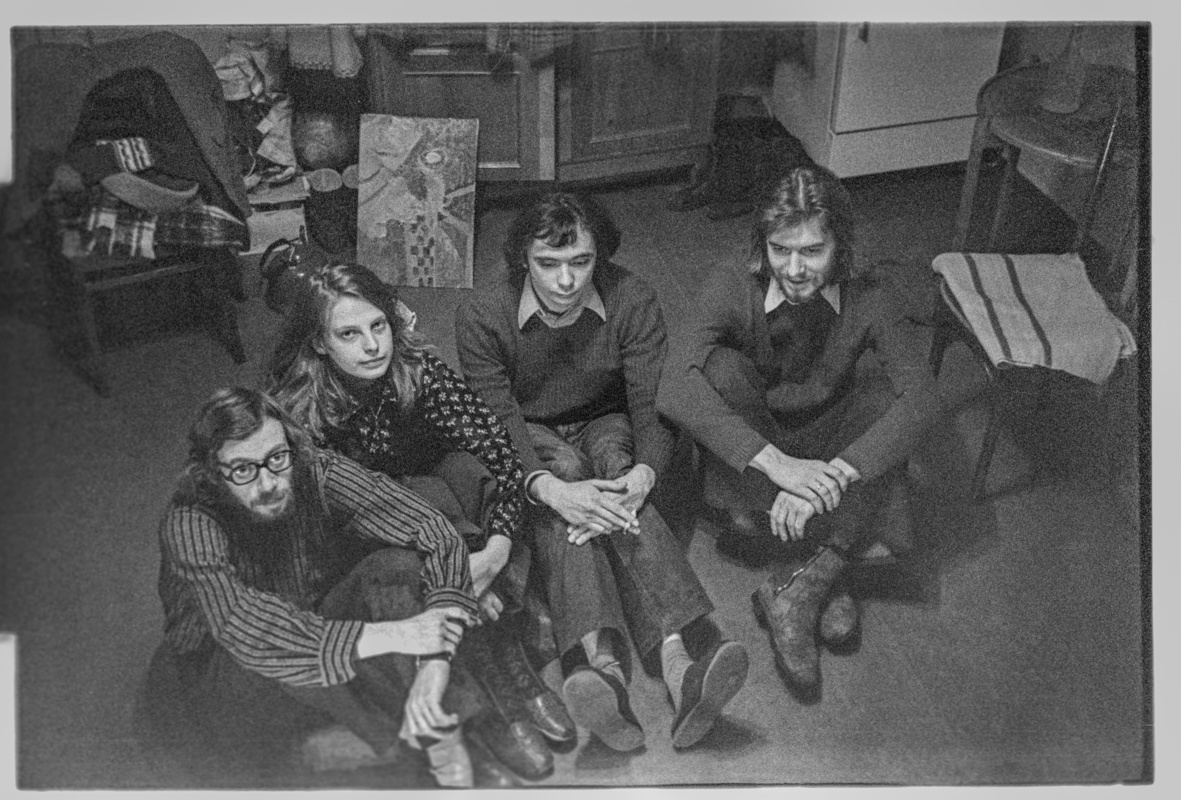

Our circle already existed: the archive wouldn't have happened if there hadn't been a circle. It formed around Collective Actions and the discussions we had about the actions. This is obvious if we look at photographs from the time. All the people who defined our circle appear in the documentation for the first volume of Trips Out of Town. There were also one-off events where everyone gathered: one-day shows at Kuznetsky Most exhibition hall or at the City Committee of Graphic Artists on Malaya Gruzinskaya Street. But there wasnít a single cluster of texts. First the Trips, then the first MANI volume became the key publications that defined the circle, representing the time and recording the discourse. That turned out to be of importance to everyone and so we continued to work on compiling MANI folders.

Each folder was made in an edition of four. Ilya Kabakov and I had the right to retain a copy: that is why we had the complete series. I believe Anatoly Zhigalov and Natalia Abalakova also had the full set. One copy of each edition was always changing hands. The only folder I didnít have was the last, fifth folder, which Toadstool group and Kiesewalter started working on together. The Toadstools eventually gave up, but George finished it. My copy is in the Zimmerli Art Museum collection.

A-Ya magazine, which included articles on Soviet unofficial art, was first published in Paris in 1979. The first MANI folder was completed in February 1981. If we compare the two, there are, of course, differences. The folder format is reminiscent of the portfolio of manuscripts submitted to a magazine, a material resource for a forthcoming publication prepared for future analysis. The other difference is that, unlike an archive, which contained objects, a magazine has neither original photographs nor physical objects. All of this was included in MANI. For example, my object Spool (1982) was specially made in an edition of four to go inside each folder. Gennady Donskoi made a secret object that was presented inside a sealed envelope. Nikita Alexeev included his absurdist advertisements on thick paper with his telephone number on them. The significant features found in MANI are its materiality, objecthood, and texture.

The most precious things in any archive are contained in objects: the color and scent of paper from, say, 1976 or the particular aesthetics of a typescript. In this sense, any archival document is priceless. All these handwritten notes, stains, and creases represent a time. An archive delivers us the plastic nature and the reality of time, its materiality.

Andrei Monastyrsky (b. 1949, Petsamo, Russia) lives and works in Moscow. He is the leader of the Moscow Conceptual School. In 1980, he graduated in philology from Moscow State University. One of the founders of the group Collective Actions (1976), he became its chief ideologist and the author of most of its actions. Together with Vadim Zakharov and Yuri Leiderman, he participated in the groups Kapiton (2008-2010) and Corbusier (2009-2010). Solo exhibitions include: Empty Zones: Andrei Monastyrsky and Collective Actions, Russian Pavilion, 54th Venice Biennale, Venice (2011); Out of Town: Andrei Monastyrsky & Collective Actions, e-flux, New York (2011); Andrei Monastyrsky, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Moscow (2010); and Earthworks, Stella Art Gallery, Moscow (2005). Group exhibitions include: Russian Performance: A Cartography of Its History, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow (2014); 52nd Venice Biennale, Venice (2007); Documenta 12, Kassel (2007); and 50th Venice Biennale, Venice (2003). He has been awarded the Andrei Bely Prize (Russia, 2003) and the Innovation Prize (Russia, 2009).