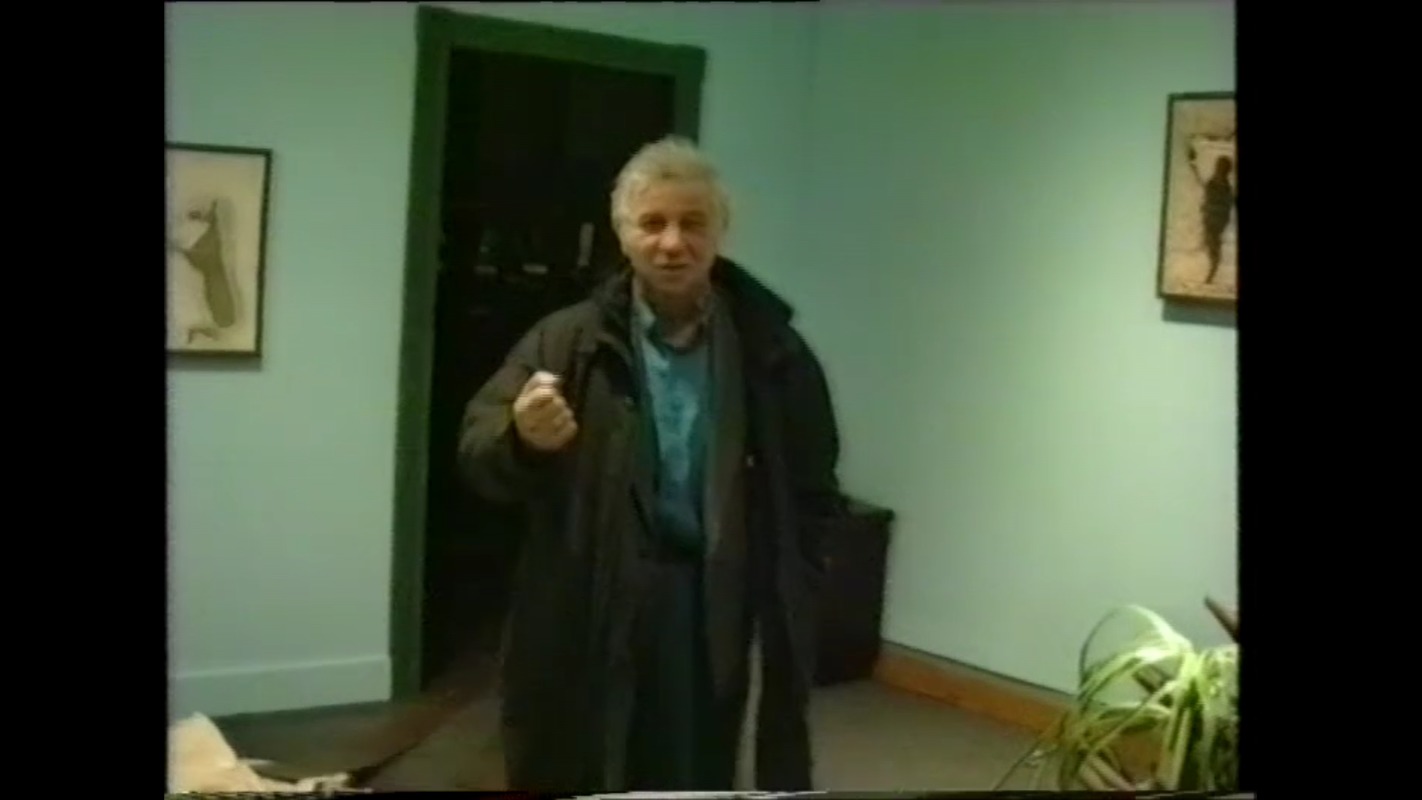

“So this is an office at the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art,” says Joseph Backstein off-screen as he begins video documentation of the exhibition Between Spring and Summer: Soviet Conceptual Art in the Era of Late Communism in November 1990. “What I want to show illustrates a simple fact that there is a lack of space everywhere. The tightness is, so to say, monstrous.” These thirty seconds serve as an epilogue to an hour-and-a-half-long recording, which, in terms of structure and content, could have been a film if the author had chosen to call it that. Subjective video sketches surpass the bare necessity of a video archive with their fascination. The camera catches an innumerable number of expressive micro-narratives that expose the feelings and hopes, doubts, delights, and fears of those members of the artistic community who get into focus.

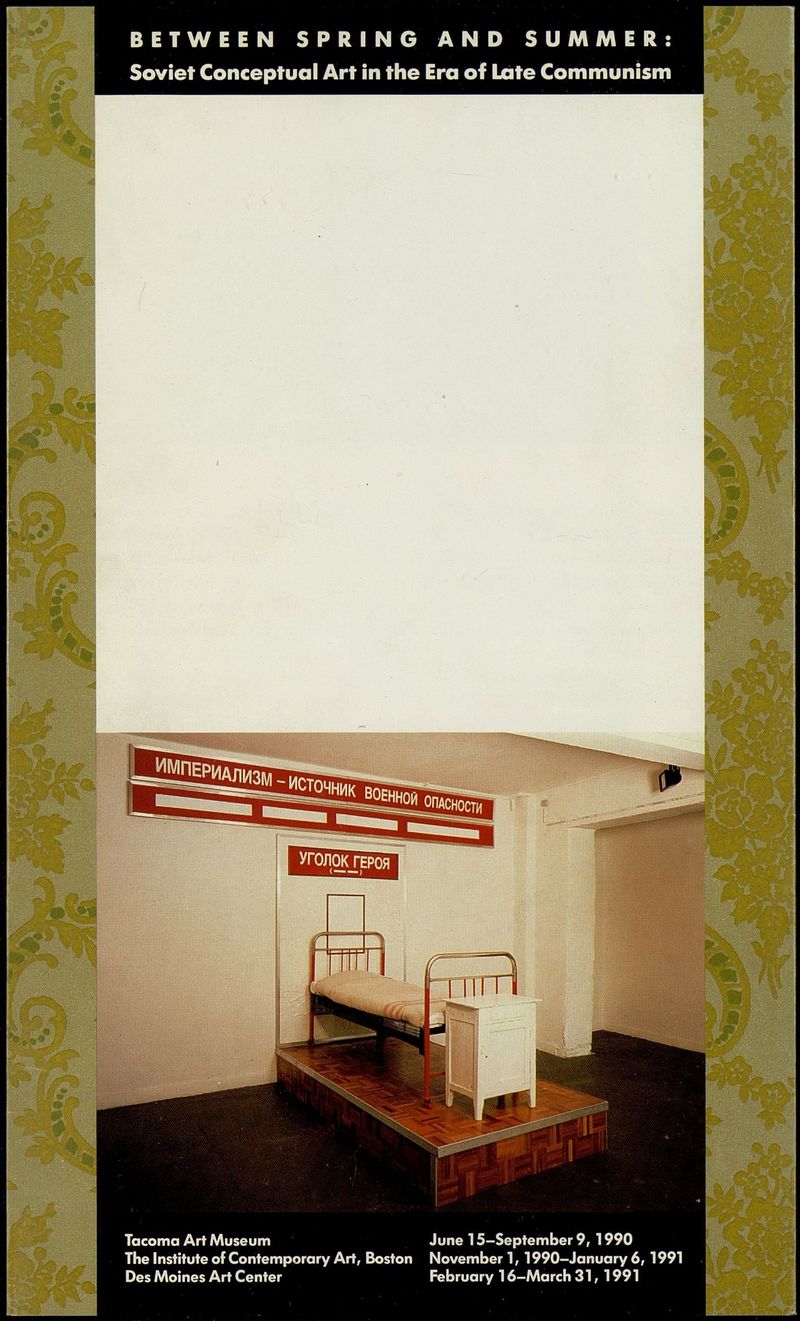

Between Spring and Summer was conceived as a part of a cultural festival accompanying a sporting event (The Goodwill Games), held in Seattle as a celebration of friendship and peace between former Cold War enemies. In 1990 the games were held for the second time—and for the first time in the United States. A museum in Tacoma (a city fifty kilometers from Seattle) invited curator David Ross, who had been in Moscow before, to prepare an exhibition of contemporary Soviet art. Ross, director of the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art, invited his deputy, Elisabeth Sussman, to participate in the project, as well as two Russian curators: Margarita Tupitsyn and Joseph Backstein. The exhibition was assembled in Tacoma in the summer of 1990; after that, it traveled to the East coast, to Boston; and from there to Des Moines, Iowa, in 1991.

Tupitsyn had lived, studied, and worked in the United States since the mid-1970s, and therefore had a good grasp of contemporary US academic discourse; Backstein was a close friend of many artists and lived in Moscow, and therefore better understood the inner dynamics of cultural discussions taking place in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Some artists went to Tacoma, some to Boston, Backstein was present with his camera in both places, recording everything, but it was the Boston film that turned out to be an unexpectedly expressive piece of moving image.

There is no pre-conceived narrative in the film: it develops by itself, over time. Formally, the recording consists of scattered scenes, long shots and close-ups, casual conversations, and random meetings.

Backstein films artist and architect Alexander Brodsky continuously for twenty seconds while the latter fixes some camouflage netting construct onto the stair railings. “You should record more interesting scenes, more!” says Brodsky to Backstein. “More?” Backstein asks in bewilderment, not understanding what Brodsky means.

For a whole minute, he films an American woman applying some putty to the wall. “I want to show the Soviet audience how real American laborers... and female laborers work,” Backstein explains to someone off-screen, clearly following the logic of Soviet production cinema.

From the same canon is the utopian scene of a communal lunch. The bell rings, calling everyone to the table. “Lunch!” someone informs Backstein.

- Where? Lunch?

- Yes, lunch!

Backstein takes the elevator, enters a room in which a dozen people are sitting at a long table, there is a case of beer on the table, people are eating soup from cardboard cups. Everyone is happy to see Backstein and his camera. “Here he comes!”, Applause. The camera finds Brodsky.

- How's the soup, comrade commander?

- Great! Very competent soup.

- A soup from a bag?

- A very good soup.

- Then I am going to eat, and then again maybe...

Backstein puts the camera on the table; the lens is obstructed by a two-liter bottle of Coca-Cola. It's hard to imagine that this is not on purpose; the frame is extremely symbolic. Off-screen, Backstein hums contentedly at the delicious food. The Americans cast worried glances at the camera and at the Russians. The Russians are discussing the influence of spicy Thai cuisine on digestion at that moment; the conversation, in Brodsky's own words, is “not for the mealtime.”

Sometimes the film turns into “slow cinema”: minutes pass in a daze, capturing the monotonous process of installation or a noisy opening party. The camera slowly slides past tense people; many of them are uncomfortable under its gaze.

The key episode is a meeting with Ilya Kabakov, already an international star, whose large solo museum exhibitions have been held in Switzerland, Germany, and the USA. Kabakov has already taken part in Les Magicienes de la Terre by Jean-Hubert Martin, and in a year, he will be one of seven artists defining installation as a genre in Dislocations by Robert Storr at MoMa in New York. Kabakov walks into the exhibition preparations in street clothes and immediately pays attention to the equipment in the hands of Backstein:

- It's so small.

- You have exactly the same one.

- No, mine is larger.

- No, you have exactly the same camera, with small cassettes.

- Yes? Yes, with small ones, but ...

- But what? Remember, it's exactly the same.

- Yours in the size of your palm, and mine...

- It seems so to you, but it's the same. The one I saw in Washington is exactly the same. It's just that the battery is located differently, on the side.

- Yes, on the side, so it looks thicker.

- Well, it's thicker.

- Although in fact, it is the same.

Immediately, without pausing, Backstein asks:

- Well, do you think this is a good exhibition?

- It's wonderful.

- In my opinion, it's very good. Here is the work Children's [by Elena Elagina], in my opinion, it's very expressive. Really good, in my opinion.

- It's fine, yes.

Quickly changing registers, switching from everyday language to theoretical, Backstein and Kabakov begin to vividly discuss Kabakov's already built installation Sixteen Ropes, a dark room in which ropes hang with pieces of rubbish tied to them and scraps of conversations written on pieces of paper— verbal details of communal life. You can only see what is happening inside by using flashlights, which will be placed nearby.

- So no one will go there—Kabakov says, disappointed.

- Do you think so?—Backstein answers.

- Or maybe they will—the artist changes his mind.

- Well, will there be those flashlights?

- There will be flashlights, yes... They will go with flashlights, won't they?

- If you put a few flashlights on this table, then, it seems to me, they will.

- Maybe they will.

- Yes, they might.

The artist and the curator encourage each other, persuading each other in the correctness of decisions that have already been made. Kabakov explains the meaning of the spatial design of the work:

- It is a room which you have to enter, but you cannot enter it because there is a heap of garbage hanging. This is the game. The door is the symbol of entrance. But you can't enter, because someone already lives there. There is collective life. Come in, but you cannot enter. It's fine.

The conversation quickly becomes completely abstract.

- It's not bad at all—says Backstein.

- Well, in general, life is a success—sums up Kabakov.

- Do you think? In what sense?

- No, there is such an expression. There are two such ambiguous, capacious expressions that can cover almost the entire universe of being. These are two such expressions: the first is “life is a success,” and the second is “to the warehouse.”

- Well..?—Backstein repeats discouragedly several times: in their community, they do not usually argue, as any thinking needs to be supported and developed; there is a discursive space of freedom. - Who or what?

- “To the warehouse.” Well, what I am saying is that this is a completely overarching concept. “Life is a success”—and you can immediately understand that everything is lost and gone, but on the other hand—you should not care about it. What does “life is a success” mean? This is a nonsensical phrase. How can it actually be a success? “Have you had lunch? Well, fuck you. Let's go home.”

- That is, the condition is not recorded in any way. It moves on and is not fixed.

- Yes. There is no specific point.

- Meaning is a special effort to introduce meaning.

- On the other hand, this is a very contact phrase because it kind of means “well, fuck you” in that sense. That is, “How's life?” Indeed, in essence, many greetings, “okay” or “alright,” mean “well, fuck it.” “You have asked? - Well, go your own way.” A huge number of expressions are the protection of a person from others. “Is everything all right?”—“Amazing!” This is the form, so to speak, “I see you, goodbye”; “what business of yours is it how I live?” It seems to me that the same thing happens here.

- This exhibition—does it confirm or refute this observation?

- Which exactly?

- Well, there, “let's move on.”

- “Let's go further,” yes, everything is passing.

- There is such a feeling.

- On the way. Let's go. There is no truth or meaning anywhere. Like a full, final meaning. Everything is tourism.

Kabakov formulates one of the basic principles of postmodernism, the rejection of absolute values and universal principles. Backstein tries to clarify:

- Well, well, if meaning is a procedure of adding meaning to something ...

- No, no, the fact is that it's impossible to know the meaning at all. But here's the trick, “it's not in this place.” That is, the meaning is not rejected at all, but it says, “do not look for it in this particular place.” Modernism was focusing on some place, in which it was believed that “the truth was precisely in that place.”

Kabakov confidently operates with concepts from trendy contemporary philosophy. The camera focuses on his face. “Modernism” and “postmodernism,” “structuralism” and “scientific”—the artist gets visible pleasure from juggling terms. He comes to a description of the exhibition:

- The same is with this exhibition. It's amazing. But one does not need to look at it, neither at individual objects nor at the general concept; you don't need to look at it at all.

“This is a completely new type of exhibition,” Backstein rejoices.—It is absolutely not necessary to watch it, in fact, just like our texts—it is absolutely not necessary to read them. It is a text that operates with its own extra-textual circumstances.

- It acts by the very fact of its existence because, without the fact of existence, no text is possible and unreadable, if I may say so.

- But it exists, there is still a text. There is some of its energy; there is an opportunity to enter the space of the text.

- Moreover, it is an enumeration of the possibilities of truth. But it deliberately contains the idea that nothing will change from sorting them out. But the enumeration itself is a very important activity.

- But our texts, about which we talked today, are arranged a little bit differently ... After all, what..?

Kabakov smiles tiredly and ends the conversation, interrupting: “We are going to have dinner now, I will then later... I suddenly remembered that they are waiting for us.”

The evening reception. Backstein greets friends and colleagues. They make fun of his camera; the camera is still a major character of the film. An employee of the institute asks Backstein if he has permission to film. “I am the curator of this exhibition!” “Ah, everything is fine then…” the young man is saying, embarrassed. Some girls are laughing.

Backstein runs into Margarita Tupitsyn and her husband, Victor. Margarita mockingly addresses Backstein:

- Vertov? Are you Vertov?—in those years she had begun to research professionally into the role of photography and photomontage in the Soviet avant-garde.

Backstein triumphs:

- I'm just like Dziga Vertov!

- You are Dziga!

- Fuck off with your camera, bitch!—someone says jokingly off-screen, Victor, as it seems.

- Hello, comrade Vertov. I mentioned you in my last article on photomontage,—boasts Margarita.

- How come? What for?—Backstein is confused and flattered.

- Vertov! Not you,—Margarita dismissively throws a goodbye, and she and her husband are gone.

Backstein gives someone a camera, after which he introduces himself to artist Nam June Paik and begins to discuss something with enthusiasm with him. Backstein sheepishly asks that they turn off the camera. Later, Russian artists gather in the office. Artist Irina Nakhova praises Margarita Tupitsyn's style. Backstein reports excitedly:

- Kabakov is now standing there, talking to Nam June Paik. Would you like to meet Nam June Paik?

- Paik ...—Nakhova repeats uncertainly.

- He turns out to be Korean, says Backstein.

- Listen, is it him?!—Nakhova is amazed.—I was always sure that it was a broad. How did I become sure that he was a woman? I was completely confident it was a broad! Frankly, I never had any doubts that he was a woman.

- Well, he looks like a woman, by the way, someone replies.

- He's in a way a little hermaphroditic,—confirms Backstein.

- Moreover, his works, it seems to me, are feminine works, continues Nakhova. —With televisions. It seems that a lady made these works. I do not know why.

Suddenly, she realises something, takes a bundle of invitations to her upcoming solo exhibition at the Phyllis Kind Gallery in New York out of her bag and hands them out to everyone present.

Ann enters the back room, apparently an employee of the institute. “Are there always so many people at openings here?” Backstein asks her in clumsy English. Margarita Tupitsyn repeats his question with a pure American accent, but Ann has already begun to answer: “No, this is a very, very good audience. I have only been working here since the Mapplethorpe exhibition, but apparently it is a very good number of people, better than usual.” In parting, she says: “You should pat yourself on the back.” Tupitsyn translates that to Bakstein:

- She says pat yourself on the back.

- What does that mean?

- It means good boy.

- Who is good? I'm good? Because of what?

- A boy.

- Is the exhibition good? …—Backstein's question remains unanswered; the audience returns to discussing Nakhova's exhibition.

The rumble of the reception again. At one point, Backstein is noticed by Andrew Solomon, a journalist who came to Moscow in 1988 to cover the Sotheby's auction. He made friends with Soviet artists and wrote a book about his adventures in the Soviet Union, entitled The Irony Tower, which will be published in New York next year, in 1991. In November 1990, he is again in the USA and is glad to see Joseph: he picturesquely throws up his hands and pronounces solemnly, and for some reason with a Russian accent “How are you?.” After that, he introduces his friend Catherine to Backstein and asks him for a new Moscow number of artists Konstantin and Larisa Zvezdochetov. In the future, Konstantin will be the editor of the Russian edition of the book.

In addition to the catalogue of the opening exhibition, which later became an important document for art historians, the museum store sells a catalogue of Kabakov's exhibition Ten Characters at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York (also shown in London and Zurich), a catalogue of an exhibition of Russian Constructivism at the University Museum in Seattle and the Walker Center for the Arts in Minneapolis; and the memoir of Andrei Sakharov. 1990 is the height of the Russian boom.

The next day, Backstein takes a long shot of the exhibition.

- Film the “Work,”—Elena Elagina points out.- Which work?

- It's really, very famous, this thing.

The camera zooms past a huge yellow panel made by the Inspection Medical Hermeneutics group, on which the word “Work” is written in Russian. In front of the canvas, there is a heating fan directed at it, which is a part of the work.

- Which one?—Backstein does not understand.

- This thing—in the reflection, you can see that Elagina points to “Work” with her hand. Well, you see, it is printed in all the newspapers.

- Yes—Backstein says, and does not move the camera.

Instead, he points it at the camouflage netting that Brodsky was installing at the very beginning. “Well, this is that bullshit,” says Backstein. “Quiet, quiet!”—Elagina pulls him back. “Yes, it’s a failure, of course, that work,” Backstein expresses an unexpectedly critical opinion as if agreeing with someone’s opinion expressed earlier.

They move on.

- Provide explanations—offers Elagina.

- This is the work of Komar and Melamid.

- This is their room.

- Yes, this is their room.

The works of art are “named.” The figures of the authors are sufficient to determine the position of their works in the world.

The camera is filming a TV-set showing a movie about Collective Actions. In the film, Backstein walks through the Kievogorskoe field and talks in English about its significance for the art community: it is “a symbol of the independence of unofficial art.” Backstein in Boston recaptures his own statement, recorded in Russia for a US-exhibition, with a hand-held camera; there is a “stringing” of locations happening, girdling of space, the figure of Backstein occupies the whole of it, both here and there.

Backstein aims the camera at Andrei Monastyrski's Finger. “Monastyrski and Hänsgen” says Elagina.

- Is this the work of Monastyrski and Hänsgen?—asks Backstein, the curator of the exhibition.

- Yes.

- Indeed, huh?

- Indeed.

- Both of them, right?

- Both of them.

- We are going to show the label.

- A close-up of the label.

The camera aims at the label, which has only the name of Andrei Monastyrski. The shot is interrupted.

Backstein and Elagina go further. Visitors with flashlights walk inside the Kabakov's installation. “Can you see anything?” asks Elagina. Say “This is the Kabakov room.” Backstein obediently repeats: “This is the Kabakov room.”

Next frame, next work. Elagina says off-screen: “He wanted her name to be on the label, but it is not. Rita also said ‘film.’ What is here to film?” Obviously, they are talking about Monastyrski and Sabine Hänsgen. Indeed, Monastyrski subsequently criticised Backstein for the fact that his instructions had not been followed (see the dialogue between Monastyrski and Igor Makarevich in the video archive of Igor Makarevich: IM-2-3-V7414).

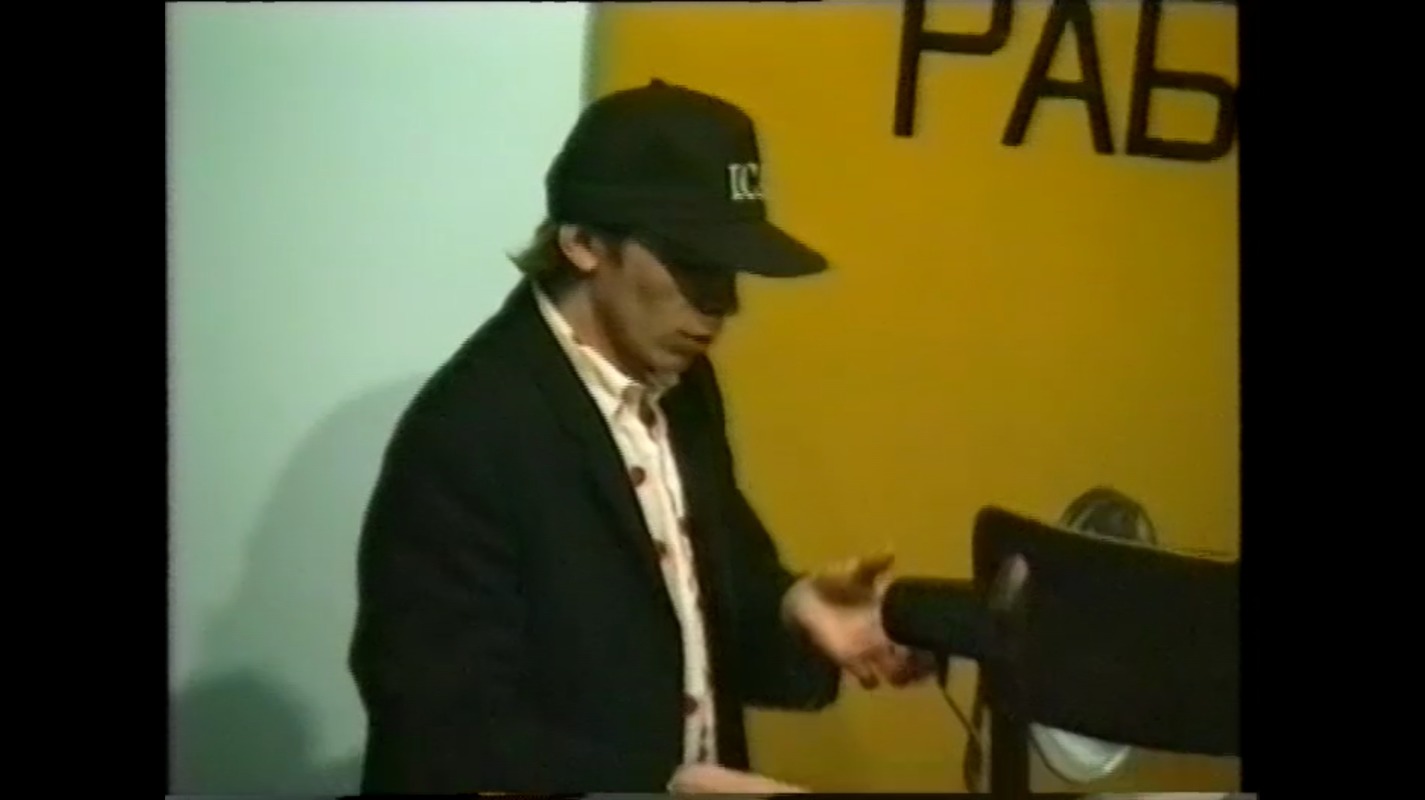

Backstein notices Sergei Bugaev (Afrika) standing in the doorway with Irena Kuksenayte. After starring in the cult film Assa by Sergei Solovyov, Bugaev-Afrika is the star of the USSR. He looks stylish: he wears a cropped suit, a white shirt with large red polka dots and a baseball cap with the ICA logo. His work at the exhibition is a dedication to the member of Medical Hermeneutics, Sergei Anufriev: an altar with his images in the exhibition hall and a banner hanging on the building of the institute. The banner has a profile portrait of Anufriev, accompanied by the inscription “Anufriev does exist, Anufriev did exist, Anufriev will exist”: a paraphrase of the slogan about the eternally living Lenin, propaganda turned into an advertisement for a fashionable artist.

- Seryun, are you leaving?—Backstein turns to him.

Afrika asks where Margarita Tupitsyn has gone, and then pays attention to the Medical Hermeneutics installation, consisting of Christmas trees, around which soft toys in white angel (or hospital) robes lead a round dance:

- I wonder what will happen with the Medhermeneutics installation Little fir-trees?

- I think we will sell them,—Backstein replies semi-ironically.

- Do you think so?

- Of course.

- To whom?

- What do you think, nobody is interested?

- To the Russian Museum,—suggests Elagina.

- If only, Afrika says sceptically.

- Can you give us any commentary on this exhibition for the film?—Backstein asks.

- Sure,—Afrika answers, and gives a speech:

“Here, in this part of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, is the most pleasant part of the exhibition. It shows several works by the Medical Hermeneutics group.”

Afrika is a Saint Petersburg artist. Traditionally, unofficial artists from Moscow and ones from Saint Petersburg did not understand each other very well. Artists from Saint Petersburg were more fashionable and sensual. Muscovites were smarter and more conceptual. Artists in Saint Petersburg played in rock bands; Muscovites published books. Muscovites drank, residents of Saint Petersburg used drugs. The members of Medical Hermeneutics, primarily Pavel Pepperstein and Sergei Anufriev, were disciples of Monastyrski and the successors of the Moscow Conceptualist tradition, but became close friends with Afrika; Afrika was a disciple of Timur Novikov but became close friends with Anufriev and Pepperstein. All three were sceptical about the contemporary art industry.

Afrika walks around the Medical Hermeneutics installations and makes a speech about “wonderful works,” “unique elements,” and “psychedelic content.” He confidently touches the works, reads their titles on labels, and it is very hard to hear him.

- The most extreme aspect here is, of course, that the heating fan continues to operate during the whole term of the exhibition. Although it is not very clear what it heats. Here it warms up the “Work”— Afrika touches the warm surface with his hand. The “Work” is pretty hot. And it also warms our hearts with its ridiculous appearance.

Afrika continues to speak, approaches the fire extinguisher and picks it up:

- I really like to pay attention to the invisible parts of any installation. For example, this can, or, as they call it here, “my friend.” “A working model.” It is a constantly present messenger.

Backstein gets tired of Afrika's clowning: “Okay, thanks!”

A street scene. Backstein asks Irena Kuksenayte, an actress and wife of Afrika, what she thinks about the exhibition. She is not in the mood and complains about a meeting with Slavists that day, apparently at Harvard: “The shittiest establishment I have ever been to.” And then she criticises the local fauna: “Thick fat squirrels, not adapted to anything. Bloated capitalist squirrels, they look a lot like gluttonous rats. Ours are red-haired beauties! What can I say.”

Afrika brags about his purchases: recently released “Industrial Symphony No. 1” by David Lynch and Tibetan music cassettes. Irena asks him if there was “Wild at Heart,” but Afrika either doesn't hear or ignores the question.

Backstein returns to filming the exhibition. The camera captures works by Timur Novikov, Sergei Mironenko, Brodsky and Utkin. “Actually, I've already filmed it.” Elagina and him go up to the first floor. Backstein gives Elagina the camera and enters the frame. Elagina introduces him: “Here is our curator. Joseph Markovich, say a few words.” Backstein points to a small tower with a roof next to him:

- This is a work by Kostya Zvezdochetov. Ilya Iosifovich [Kabakov], when he saw it, jumped up out of joy. He said, “Here, it's real art.” And I said: “Indeed, real art. Zvezdochetov is our main genius.” On that, we agreed with Ilya Iosifovich.

“Now say a few words about Larisa Zvezdochetova,”—Elagina asks, pointing to an installation consisting of a Soviet carpet and two chairs.

- This is our second genius, Larisa Zvezdochetova. The good thing about this work is that you get to sit on an artwork. That is its main meaning.

Backstein goes on to another work by Konstantin Zvezdochetov, an object made of a door, a shelf with a crossbar attached to it, an apple on the shelf, and a rushnyk hanging on the crossbar.

- This is something so incomprehensible that it is even difficult to comment on. Although it seems to me personally that Kostya's works are so good because they are absolutely uninterpretable, but at the same time they seem to be absolutely reliable and objective. That is, the image is visible, but absolutely not observed and not interpreted.

In fact, this installation by Zvezdochetov belonged to a series of works illustrating the three main rules of architecture formulated by Vitruvius: “Firmitas, Utilitas, Venustas.” The apple stood for utility, the door for firmness, the rushnyk for visual pleasure. The rushnyk belonged to the family of Larisa Zvezdochetova, so when, a few years later, Margarita Tupitsyn announced that the Guggenheim Museum wanted to get this work for its collection, Zvezdochetov refused to sell it, saying that the family heirloom was too precious to give it away.

Backstein gets distracted by the camera lens. “You're getting too close,” says Elagina. “I see, there is something ... I must blow, probably,”—says Backstein, and indeed blows into the eyes of the viewer, destroying the “fourth wall.” Then they continue.

- “Peppers.”

- Yes, these are “Peppers.”

- Here, as they say, you can't say anything.—Backstein gets tired of talking, Elagina leads the camera in a circle. “That's all, good. Everything has been filmed already,” she sums up—"turn it off.”

They actually turn off the camera, but then turn it back on to show a few more works. Backstein laments that he wanted to hang Maria Serebriakova's work—a series of collages made up of found photographs, scraps, and drawings—back to back, but he was persuaded to give each frame space. He does not talk about the work itself.

Finally—an installation by Afrika about Sergei Anufriev:

- This is the work of the main artist of our times, Afrika. It’s such a masterpiece that there are simply no words. Seryozhenka should be very pleased. Such a trick-on-a-stick for him.

Backstein is not worried that he has nothing to say about some works at the exhibition that he is curating. The main thing is their presence. The main thing is the pleasure that all participants get from their existence in the culture. Descriptions of the works are again reduced to the nominal names of their authors: “Volkov,” “Vadik Zakharov”: both are represented by painted canvases.

“Vadik,” “Seryozhenka,” “Seryun”—the tradition of calling each other with diminutive forms of names will be contested by the next generation of artists who will refer to each other solely by their surnames.

Backstein begins to talk about the attitude of Soviet artists in regards to painting, and utters an unexpected tirade:

- This is such a strange situation that in contrast to Western art, where the pictorial period and the conceptual period alternate with each other, and during the conceptual period the works stick to some compulsory formal pictorial minimalism. In this case, such a strange effect appears, that here the works are undoubtedly and unequivocally conceptual, but for all that, materiality, “perceptible objectivity” in them does not go anywhere, it stays here.

Elagina shows the works of Sergey Mironenko and Andrey Filippov. Backstein discusses Boston with an institute employee holding fire extinguishers.

The final scenes: we see the ICA office again, in the afternoon, Elena Elagina calls Moscow by phone, Backstein asks her to tell “their Moscow friends” where they are, thereby reminding us for whom he is filming all of this. He shows them “pretty corners,” Victor Tupitsyn, the library, the kitchen, the director's office, and the freeway visible from the window.

And now it is night again, Backstein gets into the car in order to go, apparently, to the airport. He films the outgoing road through the rear window for a while. “I love this kind of filming,” he explains to the interlocutor. “It's quite informative, actually. It still gives some idea of the city.” Nothing is visible in the street, only street lamps and headlights of other cars. The microphone is clogged with road noise and occasional sirens. Backstein complains that the battery is nearly empty. The adventure has come to an end, but the adventure of contemporary Russian art is just beginning.