Anthropologist Vita Zelenskaya and I began our study of apartment galleries as independent researchers in autumn 2016 by interviewing five apartment gallery curators in St. Petersburg.[1]

In December 2017, we presented our project at the program Weekend Faculty at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. In summer 2018, Garage invited me to take part in the program Archive Summer, where I studied the archive of the research and exhibition project Open Systems. Vita came with me and for a couple of weeks we worked together. We never stopped discussing the research, and although I am writing this text alone it is essentially co-authored by Vita.[2]

In this text I focus on two galleries, drawing on the materials that Vita and I collected in St. Petersburg as well as on materials from the Open Systems project.[3]

Egorka Communal Gallery

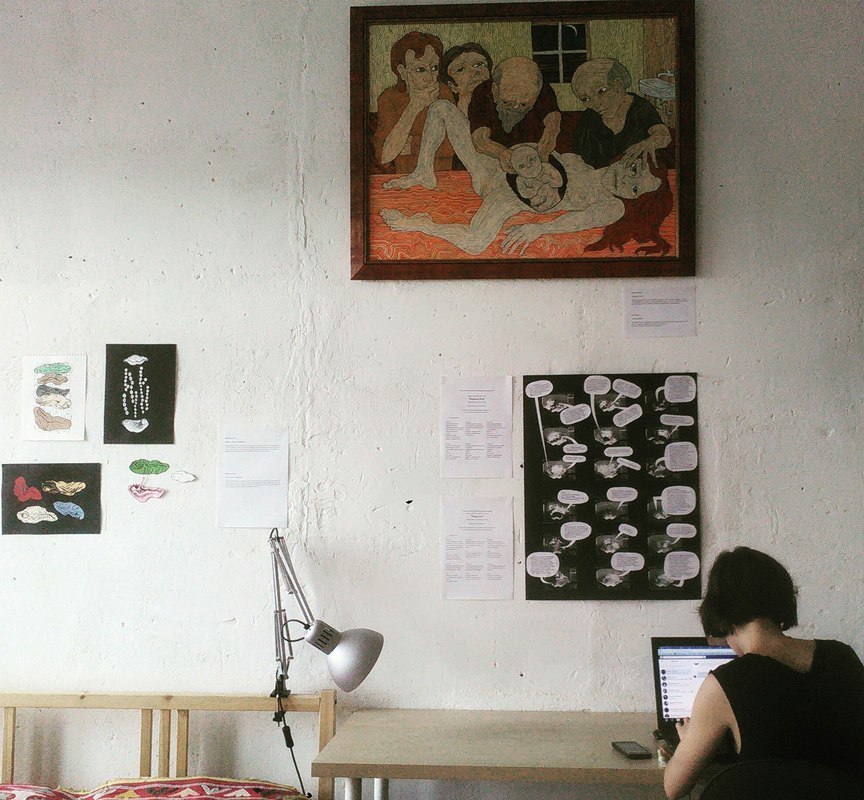

Egorka Communal Gallery is a project by the the artists and curators Nastya Makarenko and Anya Tereshkina. The gallery is located in a three-bedroom communal apartment in Egorova Street in St. Petersburg. The gallery space grew over time. Today it occupies two rooms (Nastya’s room has become the Small Gallery, and Anya’s the Big Gallery), the long corridor, and the kitchen. The third room in the apartment is not part of the gallery.

Egorka opened at the end of 2016, when Anya and Nastya moved into the rooms they bought (Anya) and rented (Nastya). The first exhibition took place in Anya’s room and the second in Nastya’s. At the time, third room was occupied by an elderly neighbour, Vladimir Aleksandrovich.

The first project (and the only one in 2016) was a group exhibition of Anya, Nastya, and their friend Pavla Markova. In 2017–2018, Egorka showed four large group exhibitions, as well as an exhibition by the Gallery’s research department (a sub institution within the gallery devoted to the translation and study of feminist texts on art).

The last exhibition at Egorka (at the time of writing) was Support Group for Those Perturbed by Eros (October 27–November 23, 2018), the most representative show in terms of artist numbers and geography. It focused on the states of infatuation and anxiety.

During work on the first exhibition (which opened on December 8, 2016), the gallery team formulated the first part of the “Egorka Principles” (a second part was added later). The story of their creation is so closely tied to the history of the gallery and its exhibitions that we can use it as a guide to understanding the gallery’s ethos.

Ethos here refers to practice, lived ethical principles, ethics-in-action, a worldview that takes shape in action, the everyday permeated by theory, art, and values, the connection of small and hardly visible that has difficulty gaining a voice, that which is most important. This was the special aspect (hard to catch and requiring great sensitivity), the constitutive trait that I searched for through work, conversations, observations, and discussions at Egorka. Ethos is “what” [is being done] merged with “how” (pragmatics) and “why” (values).

The gallery’s “principles” are one way it represents itself in the public field. It is easy to see that they are not addressed to a third-party reader but to the organizers of the gallery themselves. Turning of the private and intimate into something public is a facet of the politics of vulnerability: by sharing their doubts and uncertainties and openly speaking of traits that the culture connects to “weakness,” the Egorka curators talk to the viewer as a friend, the personal tone shortening the distance between them.

The friendship that is at the heart of the curators’ interactions at Egorka defines the relationships inside and outside the gallery. The boundaries between private life and work are blurred and communication practices are stitched together to become hybrid forms: friendship-as-work and work-as-friendship.

Apart from the tension between the private and the public, art practice and curating, Anya and Nastya are interested in the tension between the individual and the collective, and Egorka has become a space where this tension becomes tangible, a space of potential conflict and the search for balance.

Marina: I’ve got a silly question. Because it is called Egorka [a male name], because of the way it sounds, the gallery, which is feminine [in Russian], has turned into some sort of a queer subject in my mind.[4]

Nastya: When we last came to FFTN, Ira Aksyonova[5] met us with the words “Here’s Egorka,” so you see people think of us as a single organism, a subpersonality. Conversations that take place here turn into exhibitions, into friendships that also become exhibitions of a sort. […] I understand this kind of friendship very well, for me it’s a form of connection between people.

The subjectivity of Egorka is formed through language and through media (social media posts, announcements, avatars, and memes). The anonymization of the curators’ speech on the gallery’s public pages on VKontakte and Facebook might not deceive anyone (since there are only two possible authors), but it supports the building of the collective subject. Egorka talks to us from the web pages, thus becoming increasingly recognizable. The ambivalence of the name is used playfully in the gallery texts, where it occurs as a toponym (“At Egorka…”) and as the name of a subject (“See you Tuesday. Yours, Egorka” or “Egorka is looking forward to your visit”). This principle became most apparent during the preparation and showing of the group exhibition Support Group for Those Perturbed by Eros, when Anya and Nastya announced a closed call, inviting artists they knew to take part in an exploration of infatuation and anxiety.

Nastya: Originally it was meant to be an exhibition of no more than ten artists from the feminist support group.[6] And then, I don’t know, I guess we just talked a lot about the idea and it resonated with people. So, in the end we had many more participants.

Curatorial Strategies

Here we look at what is usually referred to as curatorial strategies. The closed call, as opposed to an open call, is one of them. The number of participants through the “closed call” increases, but without the loss of immediate contact: I trust you to invite an artist you trust. The same close relationship and trust show through the curators’ texts for the exhibition Support Group.

“—The idea for the exhibition emerged from the synchronized, anxious infatuations of the gallery’s curators.

—Infatuation is anxiety, whether your feelings are reciprocated or not. It always destabilizes you, creates this turbulence in the background. […]

—One is anxious both in the presence and the absence of the object of one’s affections.

—You can close your eyes and not look.

—You get relief from a long walk and a talk; from writing texts or songs about it; from drawing or photographing it.

—We are looking for support from those who are anxious like us, and we want to support them as well.”[7]

Another important principle is the dedication to flexibility and changeability that is an extension of practices of self-care. Tired of open calls, the two curators invented a “closed call;” they keep changing the opening hours, giving themselves time to rest and space for experiments with quasi-institutional formats of work/leisure (for instance, Egorka has a translation studio and a film club).

The gallery’s political principles are inseparable from its ethics.

Marina: Does Egorka have a particular political stance?

Anya: I believe it does. We as people have political principles. Hmm… Well, first, we are feminists… I am very into… Marxist and anarchist theories and the people who put them into practice… the questions that are discussed in those circles. Polina Zaslavskaya’s words really stuck me when we talked about doing art politically instead of making political art. What I mean is that instead of saying “feminism” ten times in a text, one can produce a work or an exhibition in accordance with its principles, without offending anyone or trying hard to show something that is invisible.”

[Talking at the same time]

Anya: We want to support women artists.

Nastya: We also show works by people who do not consider themselves artists and whose main occupation is elsewhere, they simply make art works. Their status is of no importance.

Anya: It’s true, friendships matter. If someone we don’t know asks us about having a solo exhibition in our gallery, it’s not easy for us to agree to that, so in the end we say no.

Nastya: …because it’s our private space and we cannot let in someone we do not know at all.

Affective Strategies

What I call affective strategies are not intuitive but conscious efforts to preserve and grow emotions that are valuable to those living them. They are an example of strategies of self-care and care for one another. These strategies occupy an important place in Anya and Nastya’s curating activities. An exhibition can be seen as a reason/occasion for joy, togetherness, and support and it can be organized to be so. This is hardly possible in a more professional context, where emotions and affects are seen as unwanted obstacles to work and are seldom considered. At Egorka, attention to the emotions arising during the making of exhibitions are part of the curators’ strategy, as it is precisely attention to one’s own emotional state that often brings ideas for exhibitions, and attention to one’s emotional balance and tiredness/burnout as curators leads to the adjustment of the working process, the rhythm of exhibitions, and the format of artist selection.

Nastya: The birth of an exhibition, working on the idea, writing the text makes us happier. It’s like exhausting childbirth, with a partner.

[Laughing]

Nastya: Yes, I realised, more than ever during the latest exhibition [Support Group for Those Perturbed by Eros], that I want as many people as possible to see our projects. When we had solo shows, sometimes no one at all would come for the opening, and that felt very hurtful. […]

Marina: What else do you find particularly satisfying in your practice?

Nastya: I enjoy the process of organizing the display, when we finally get together and decide what will hang where and how it will go together. That’s like writing a symphony. [Laughter] And it turns out that interesting connections can be made between works, that if you sit with them and move them about for a bit you get an interesting and beautiful story. Everything is very organic.

Feminist Ethics as a Key to Understanding Egorka

The transfer of the feminist practices of mutual support—such as support groups—into the exhibition format (as in the case of the exhibition on anxiety and love) is far from accidental. Indeed, it formalizes the principles of feminist ethics and politics discussed above. I have been unable to find a single aspect of Egorka activities that were not feminist.

Egorka knows how to protect its boundaries. Its practices are not subversive, mimicking—or aiming to evade—the rules of the game in the “big world” outside its walls. Instead, it is the making of a separate world where a different kind of action is possible. Of all the apartment galleries that Vita and I have visited or studied, Egorka may be struggling most with turning a private apartment into a public space (as one of their texts points out, “the people living here are introverts who like to make things happen”). It is precisely this effort, this difficulty that makes the gallery project so important and well thought-through, but also stubborn and persistent in asserting its difference. It is also important because the private, the political, and the creative are merged into one in their space, practices, and relationships. The dedicated attention to one’s own state and the resulting flexibility and willingness to change have turned from a personal and therapeutic practice into a curatorial strategy.

During my work in Moscow for Archive Summer I came up with the image of grass—a quiet but persistent growth that softly conquers its territory—which explains everything important that I sensed in Egorka. It seems to have been a gift from my intuitive search.[8] Indeed, what we see here is the ethos of the grass that does things its own way: weaving into and not fighting; quietly growing and not expressing; listening and not asserting itself.

Anya: I guess we created the gallery searching for our comfort zone in the world of contemporary art… and maybe we continued by partially getting out of our comfort zone.

Nastya: Yes, this boundary has somehow shifted.

Anya: We continue to explore the boundaries…

Nastya: … of our refuge…

Anya: …whether it is private or public…

The refuge does not only react to triggers from the outside, but has its own policy, whose relationship to the outside world (both institutions and self-organized initiatives) Anya sums up as “doing equally” and “doing differently.”

Brown Stripe Gallery

Brown Stripe was a gallery founded by Pyotr Zhukov and Ekaterina Gavrilova in an apartment in Altufyevo, Moscow, in December 2006.[9] In 2014, after Ekaterina Gavrilova left the project, the gallery was renamed the ex-Brown Stripe Foundation. On May 1, 2016, Brown Stripe launched its side-project, 7th Floor Radio.

The gallery’s more than ten years of existence roughly coincided with a particular stage in the development of educational (and other) infrastructure in the field of contemporary art in Moscow, which had a direct influence of the lives of Pyotr and Ekaterina. Pyotr, who was a physicist by education, went on to study at the Moscow Institute of Contemporary Art and Rodchenko Art School—two of the key educational institutions that formed the landscape of emerging art—and briefly attended the Open Studios school at Moscow Museum of Modern Art. Ekaterina Gavrilova was initially a classically trained artist who studied at the Surikov Institute and the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (Animation Studio of Sergey Alimov). She also completed a program at the Moscow Institute of Contemporary Art. By the end of the 2000s, having studied in various institutions and maintaining the connections from their previous circles, they had a very good idea of art education in Moscow.

Their curating activities began long before Brown Stripe. Ekaterina curated her first exhibition in 2001: a show of student works in the small town of Podolsk. A variety of projects in all sorts of places followed: libraries, children’s drawing clubs, and city-run exhibition spaces in various areas of Moscow.

Their experience of curating exhibitions in experimental formats and unusual spaces off the contemporary art map of Moscow, as well as in those integrated into the system of contemporary art, is crucial for understanding the blurriness of the boundaries between institutional and self-organized spaces and the emergence of “gray areas” between them. While city-run exhibition spaces, libraries, houses of culture, and various children’s and youth clubs are formal institutions, they have little to do with contemporary art. Such spaces are not among the legitimized or legitimizing (through their prestige, history, recognition, benefits offered) institutions in contemporary art. These strange enclaves and strange unions (such as between the young artists and the exhibition space in Podolsk) create hybrid, flexible forms of interaction between many actors precisely because they are unnoticed by Big Brother. In the 2000s, such spaces, inherited from the Soviet administrative system, were discursively and functionally left outside the newly developing institutional system of contemporary art; beyond the hierarchies and inner boundaries of the art world. Nobody needs them, explains Ekaterina, so they have turned into spaces of great freedom.[10]

Their freedom in choosing spaces and strategies seems to define the position that Pyotr and Ekaterina occupied in the art scene, that of a flâneur who is aware of the boundaries but consciously ignores them and goes wherever they want to.

The boundaries in question include those between classical and contemporary art; visual and audio mediums, movements and schools. Their versatile education informed the great variety of styles, genres, and exhibition formats in their practice. Brown Stripe showed painting, graphic art, photographic works, video art, object and sound art, and installations that took over the entire space. It organized screenings of animation, concerts, performances, and poetry readings.

The solution—the overcoming of boundaries—consists, in this case, in the simultaneous presence in multiple zones and their non-contradictory merging within their own biography, the exhibition space or the apartment gallery.

The first exhibition at Brown Stripe was a group show in 2006.

Ekaterina: The first exhibition was a real hodgepodge. Vika [Lomasko] took part, as did art historian Nadya Plungyan, because she also paints… But it was a “here are a few works, let’s discuss them” kind of thing. And then we thought that a room that size is not great for group projects and started offering our friends who might like the idea to have a solo exhibition at our place.

Pyotr: But the first exhibition was an improvized group show. Me, Katya, Nikita Pavlov, Lyosha Dorofeev, [Maria] Aradushkina, [Viktoria] Lomasko, and Nadya Plungyan came… someone else…[11]—seven or eight people total—and every one brought a work or two. […] Later, almost all our projects were solo exhibitions.

Boundaries and the Space Where They are Lifted

Above I have already outlined the questions that proved to be central for Brown Stripe and that Ekaterina and Pyotr keep returning to in the interview: the idea of the gallery grew out of a desire to overcome the boundaries between various artistic communities and the potential and specificity of the space itself (the room, the apartment, the district, the city).

It is interesting to see how the space of the gallery and its location are discussed in the context of the gallery’s “mission;” howsquare meters are loaded with meaning.

Pyotr: It was a curious thing how a rather large community formed there. The group of people that had existed before the Rodchenko School expanded when I went to Rodchenko and communicated somewhere. Then other people joined in from different circles… and later because two or three circles came together—but did not clash—within one space, a certain conversation emerged.

Thus, the space becomes the key to understanding the initiative, regardless of the scale. The space becomes the axis around which meanings, connections, and references are formed; the space becomes enveloped in myth and connected to history; being located in a space can be interpreted both as violence and as fate.

Regarding scalability in the description of spaces, whatever scale we choose, the space is poeticized and mythologized in descriptions by (primarily) Pyotr and Ekaterina, who explain its significance thus:

1. The room (the gallery itself), its small dimensions, a single window and the view from it.

2. The apartment is located in the middle of a standard multi-story building;

3. The building itself is“strange” yet typical.

4. The district of Altufyevo is “the arse of the world” and the heir to the tradition of Lianozovo, thus sacralized by its connection to the history of unofficial art.

5. Moscow itself.

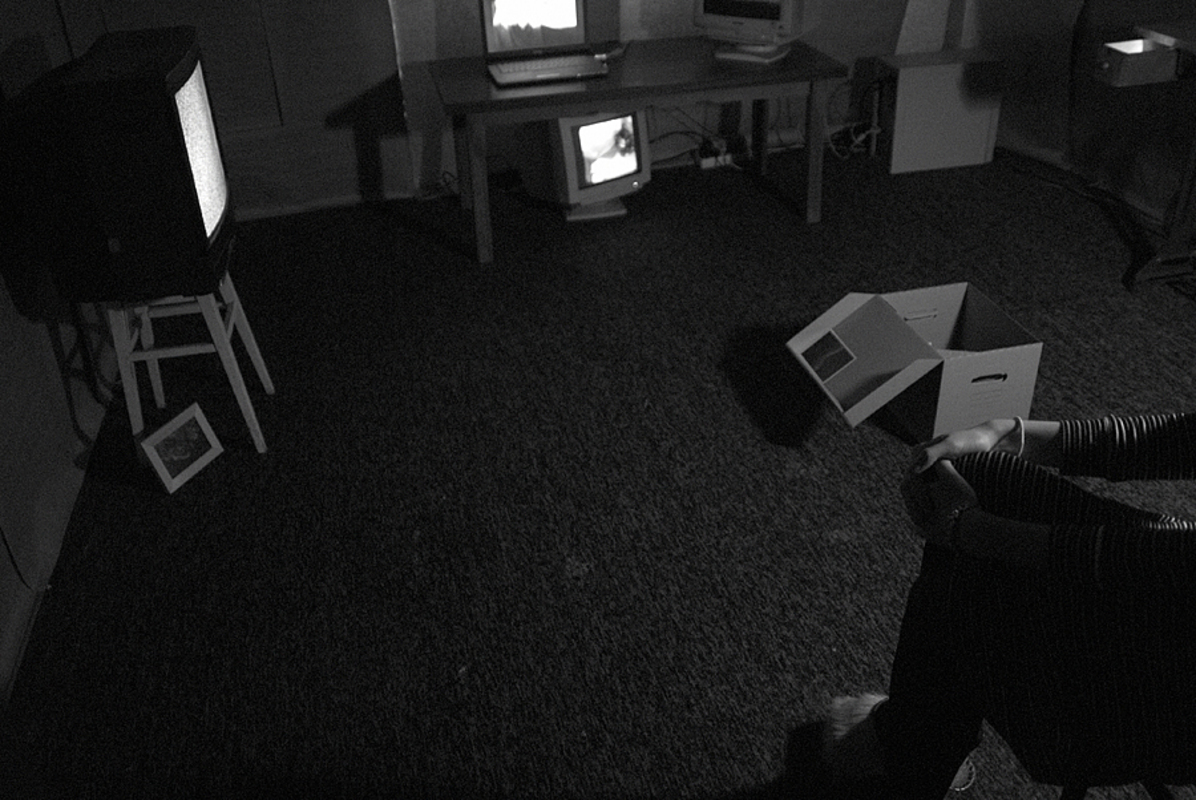

The Room

Pyotr: It was used as a kind of studio, so it was filled with stuff: an easel; paintings; a table; other things. Before the opening we would take everything out and hang the works. I guess it took us an hour or two, depending on the number of works, but it was all done pretty quickly. It was funny, as Katya also has students who came to our apartment. So, the room kept changing. We take everything out and we bring everything in and put it in the same places, only in a different order… a “schizospace.”

Ekaterina: It was a blank canvas for experiments. People like Arseny Zhilyaev did there what they would not do in galleries. Because they had complete freedom.

Pyotr: Conceptually I experienced it a as kind of cave, you know. At the time I was really interested in Abrahamic discourse, early Christianity, catacomb churches… But somehow everybody felt very minimalist about it: emptiness, minimalism, these walls, the experience of one’s path…

The District/The City

Pyotr: There was this aura, this fascination with Moscow Conceptualism.

Marina: Were you influenced by that part of the history?

Pyotr: Of course. Pivovarov’s Grey Notebooks were published around that time. I lived in Altufyevo and the barracks of Lianozovo, where Oskar Rabin and other wonderful people had lived, were just round the corner. Once I went to a shop and saw a banner that said, “Lianozovo. Worth Painting!” [Laughs]

Ekaterina: I don’t know how familiar you are with the geography of Moscow. Altufyevo is the arse of the world. We are right by the metro, but it’s the last station in the north and people really need to make an effort to get here. Strangely, at times we had a lot of people at Brown Stripe, I mean really, a lot for an apartment. […]

Pyotr: There was this aspect that I worked with a lot, that when viewers have to travel far their attitude changes. It’s not that they start seeing art differently, but they need to justify spending so much time… The location and the space inspired certain curatorial strategies. With the collective Vverkh![12] we organised a series of complex conceptualist seasonal exhibitions connected with the ideas of travel and moving. We organized the summer exhibition Nemi in Altufyevo. It was in three parts. At Brown Stripe, a performance took place in the gallery, with visitors watching a very distorted broadcast of it in the kitchen and hearing some sounds from behind the door. Then there was a trip through the Lianozovo Forest, also with Vverkh! I gave a historical tour and there were some objects and performances. Finally, there was a walk under the Moscow Ring Road, where a river crosses it through a sewer and a tunnel… In the denser forest on the other side of the road we built a dugout and made a cosmist altar. We sacrificed the only copy of the performance video documentation there.

Ekaterina: Sasha Sukhareva, made an exhibition with the things she found in the space. She moved them about and lit them up, so she didn’t even need anything special to create it.

Marina: You mean, she used objects from the apartment?

Ekaterina: Yes, such as the old Finnish sewing machine, similar to a Singer, with a table and with legs. She used it as a table and placed her photograph on the shelf. She made black-and-white blurry photographs. We showed another photographic series, actually. Anton Kuryshev photographed everything that Brown Stripe visitors never saw—things from the rooms that are closed during exhibitions because they are filled with stuff and messy. So, he photographed that mess and kind of inverted the space.

Pyotr: The name 7th Floor Radio… I grew up in this apartment. In his autobiography, The Words, Sartre says that he he grew up on the sixth floor, over the rooftops of Montmartre, and theat sixth-floor perspective remained with him throughout his life. At some point in my life, I felt that the view of Altufyevo has burnt into my eyes. It’s like a house you cannot leave and the space affects you… it sucks you in.

This experience of the space, of the presence in the space, encompasses and merges together the physical (the long journey from central Moscow, the walk from the metro) the cultural (the memory of the Lianozovo group), the infrastructural (periphery, marginality), the visual (typical box houses), the personal (the view burnt into the eyes), and shared elements (heterogeneity and number of visitors). This strong experience of the space is the key to the ethos of Brown Stripe, its philosophy, its “energy and atmosphere” (Ekaterina), and its catacomb-ness (Pyotr). This particular experience of space has to do with its sacralization, and in the case of Brown Stripe it might be difficult to say with certainty whether it is playful, subversive or serious. Discussions of exhibitions often touch upon rituals and the ritualistic foundations of art, its magical and mystical aspects, both in general and in relation to the particular artworks on show at the gallery.

The Ethos of Brown Stripe: Sacred Fun

One might assume that art understood as a ritual has to look serious and be taken very seriously, but in fact the ethos of Brown Stripe is an ethos of fun, simplicity, drive, and ease: everything seems to happen naturally. For example, their decision to have one-day exhibitions was based on the “obvious” reason of convenience. The fact that Moscow audiences only come to private views is criticised, yet immediately taken for granted and made into a rule for the organization of exhibitions.

The combination of a serious approach that elevates art, its making, experience, and discussion to the level of sacred on one hand and drive, fun, joy, and a carefree attitude on the other form an essential aspect of the gallery’s activities. There are, of course, many other important things, such as the incredible discursive density and fury of the Brown Stripe nights: endless debates, critique, the birth of theories—serious or not—active engagement in the conversation, the passion for discussion.

…

In apartment galleries, personal connections, experiences, characters, and traits determine or influence everything. But those personal aspects are in each case presented differently.

Brown Stripe is focused on the tradition of Moscow Conceptualism, the institutional system, discursive strategies, various schools of contemporary art, theoreticizing and conceptualizing one’s art, including through the ideas of the Russian Cosmism and cultural theory.

In the case of Egorka, the institutional context is of less importance (in St. Petersburg, of course, it is less pronounced). Their personal is built on different ground, including feminism, activism, and anarchism, whose ethical and political stances the curators appreciate, and to a greater extent based on the practices of active remodeling and living of the everyday: the introduction of the everyday to curatorial strategies and artistic contexts.

Or: Pyotr and Ekaterina grew up in Moscow, whereas Anya and Nastya only recently moved to St. Petersburg and their connection to Omsk is very important to them. And if the Altufyevo view has burnt Pyotr’s eyes, to Nastya curating Egorka is a “way of getting to know the city.” Brown Stripe needs to find its place in an existing and strong field (the Moscow art scene), whereas Egorka is creating its own.

Both galleries are interested in overcoming group/clique boundaries, bringing together people of different schools, movements, and aesthetic choices. Perhaps, this points to a general tiredness with markers such as diplomas from contemporary art schools, different as they might be.

A huge difference is found in the ways in which apartment gallery curators draw the boundaries between public and private: from real spatial borders to symbolic ones. The common aspect is that, however the borders are drawn, they are the topos of self-analysis and are explored in the exhibitions.

The notion of ethos, which I here use very liberally, helps me show the interweaving connections between the everyday, the pragmatic and material aspects of curatorial practices, and axiology—various methods of constructing value and assigning significance to the events that take place in an apartment gallery (and in one’s own life). The methodology of this text is based on the intuitive capture and interpretation of what I have heard, as opposed to classification; on the hope for proximity and therefore understanding. Such embodied research relying on emotion as much as on the rational was made possible by the specificity of the subject itself, and I am grateful to my informants and their living and working spaces.

Notes

[1] Marina Maraeva (Intimate Space Lab), Anna Isidis (Intimate Space Lab, Bobo Gallery), Maria Nikolaeva (Morpheus Gallery), Anya Tereshkina and Nastya Makarenko (Egorka Communal Gallery).

[2] This article is an abridged version of a text written after the Archive Summer project in 2018–2019.

[3] In this text I juxtapose various kinds of material: amateur ethnographics in the study of Egorka Gallery that I occasionally visit, and the study of the video archive and texts of Brown Stripe Gallery, which ino longer exists. I did interview Pyotr Zhukov and Ekaterina Gavrilova, but the retrospective view from quite a distance is a different thing. It was a different context, of course, a different time. The only possible solution was to compare what is comparable, for example the texts and the analysis of the interviews, and to speak of the incomparable separately, subverting methodological continuity. In other words, to write different texts within one. The key element that is at the core of my interest in apartment galleries—their ethos—can be grasped through video as well as through text and of course through nostalgic retrospective speech.

[4] Here and further, excerpts from an interview made during work on this research project.

[5] Self-organized gallery FFTN (named after the fifteen visitors that it can host at a time) and its curator irina Aksyonova.

[6] Nastya explains the support group the following way: “It’s a group of artists and activists that formed over a year ago around Sasha Kachko’s exhibition Joy 2.0 Tenderness. We gather every once in a while. Our practices vary. The main idea is to support each other through the discussion and co-production of works and in private matters. The group is formed and semi-private.”

[7] Curator’s text for the exhibition Support Group for Those Perturbed by Eros. See the online catalogue: https://issuu.com/egorka_gallery/docs/_________________________small_1

[8] “In the past few days I’ve been fixated on the idea of sharing—of the things we can share that through this sharing can connect us. One can share a bed, sadness, loneliness, ideals, a lunch, property, dreams, but most often with one other person, not many. And if we share with many, do we need one? Perhaps, if communes created by the calling of the heart were indeed possible, our habits of sharing with one person would be completely redefined. I see it in my mind as vegetation being rapidly covered with the tumours of mould that join everything into one; sparks of commonality that transform bodily structures and volumes and creates intricate and fragile, unstable queer communes. Oh mould of commonality, come cover our bodies! Meanwhile, I am currently studying self-organized initiatives, and in particular, apartment galleries, and at this stage my most important discovery is that Egorka Gallery is essentially grass—it is grass in terms of ethics.” Post from my private Facebook page, 10.07.2018. URL: https://www.facebook.com/marina.israilova.1/posts/1655624974535740.

[9] I came across Brown Stripe while studying the archive of the project Open Systems. At the time of my research the gallery had already closed. I had never heard of it before and for me it was a real discovery. In the archive I found just over six hours of videos documenting its activities, and from the first few minutes I knew I wanted to study it and write about it. What was it that excited my interest? It is both easy and difficult to answer this questions. I saw people in the bedroom, in the kitchen, by the window, talking about art; and somehow I knew that something important was happening there and that I wanted to be there. I was instantly charmed by the space.

[10] These “gray zones” or “transit spaces” may be one of the most exciting objects for research in contemporary art and they require further study, with a particular focus on the analysis of their structure and the underlying social connections and economic conditions.

[11] The complete list of artists was as follows: Maria Aradushkina, Ekaterina Gavrilova, Aleksey Dorofeev, Pyotr Zhukov, Viktoria Lomasko, Elizaveta Makhlina, Nikita Pavlov, Nadezhda Plungyan, Andrey Chizhin.

[12] The name of the collective Vverkh! [Up!] formed by Rodchenko School graduates and Brown Stripe regulars (both as artists and viewers) reflects their love for paradox and puns. Their original name, Rossiya, Vverkh! [Russia, Go Up!] was a response to the omnipresent slogan slogan of the 2000s and 2010s [Russia, Go Forward]. The upward movement referred to the ideas of Russian Cosmism. In order to remove obvious political connotations, the collective dropped “Russia” from the name, leaving the pure utopian call.