This text is based on a transcript of Konstantin Skotnikov’s paper for the conference Local Histories of Art, which took place at Garage in 2017 as part of the 1st Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art.

I’ll tell you straight, I am really impressed by the worldview of the group Blue Noses and, in particular, of Alexander Shaburov. I collaborated with Blue Noses for quite a long time, from 1999 to 2007. And I will tell you how we see the formation contemporary art in Novosibirsk. Before I left, I was asked by artist friends, “Who will you represent in Moscow?” Provincial people are always somewhat embarrassed in front of “celestial Muscovites.” I replied that everyone would get what they deserved, and I would represent the picture as I saw it. I hope that picture will become fixed.

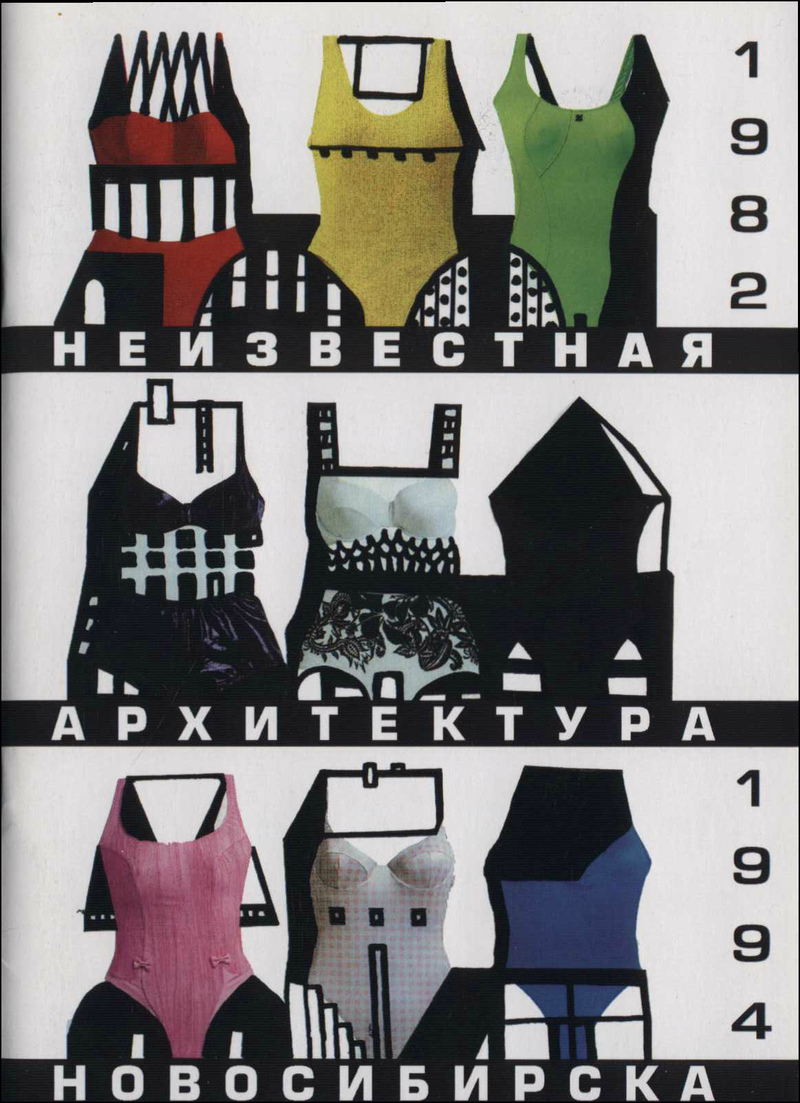

Contemporary art in Novosibirsk came out of the depths of the architectural faculty of Novosibirsk Engineering and Construction Institute in 1982 [1]. You can read about the pre-history in the brochure Unknown Architecture of Novosibirsk 1982–1994, which was published by the enthusiasts Alexander Lozhkin and Vyacheslav Mizin in 1997 in Yekaterinburg.

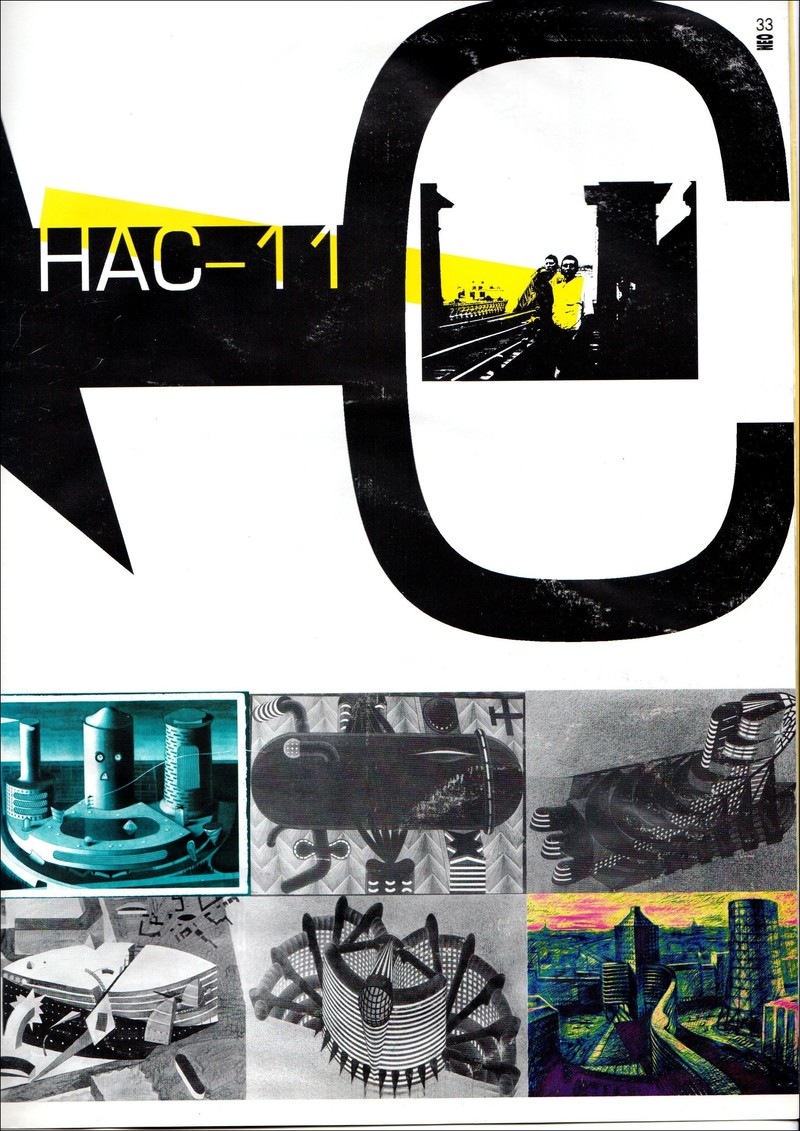

While studying twentieth-century architecture in the architectural faculty, it was difficult for us not to notice art. In the 1980s it was impossible to build anything freely and one could only fantasize on paper, making drawings and models. This was something young Novosibirsk architects began doing (not without the prompting of Moscow architect Yuri Avvakumov). Above all, I should note Sergey Gulyaikin’s group, which also included Andrey Chernov and Sergei Grebennikov, the group Novosibirsk Architectural Section or N.A.S. [2], and the design enterprise Avrora [3], which was led by Vyacheslav Mizin and Andrei Kuznetsov. They were all involved in paper architecture, fantastic conceptual projects, and graphic art.

By 1994 the paper architecture movement had begun to come to an end. Three artists emerged from it: Vyacheslav Mizin, Dmitry Bulnygin, and Maxim Zonov, all of whom were in some way influenced by the Polish magazines Projekt and Sztuka. They were also inspired by the neoexpressionists Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz.

After the demise of paper architecture, close contacts developed with friends from Yekaterinburg. Tamara Galeyeva’s report confirmed my intuitions. The first to travel to Yekaterinburg was Dmitry Bulnygin in 1994. He went to visit Oleg Yelovoy, with whom he lived, worked, and made an exhibition. Then Mizin went to Yekaterinburg. They all got to know each other in a sacred artistic space—Yelovoy’s home. That was where “Novosibirk video” started, with the help of Yekaterinburg friends.

Various artistic groups existed in parallel with the graduates of the architectural faculty. The literature and poetry group PAN-Klub, which was linked to the newspaper Novaya Sibir (New Siberia), appeared around 1990. They were very witty, interesting, and jolly people. PAN-Klub members organized the first performances. The group Cosmonauts was one of the first in Novosibirsk to work with video art. It included Maxim Zonov, Aleksei Leshshcenko, and Andrei Kurchenko (the first two also had an architectural background).

During perestroika, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a gallery movement began. Numerous galleries appeared: SibInterArt, Belaya galereya (White Gallery), Zelenaya piramida (Green Pyramid), Chernaya vdova (Black Widow), and, I should note, the completely underground group Semnadtsat nevidimok (Seventeen Invisibles), which was the gallery of the artist and poet Oleg Volov and also had an artistic-poetic character.

Among all of these initiatives and undertakings we can see the influence not only of paper architecture but also of Polish posters, the Polish journals Projekt and Sztuka, German neoexpressionism, and even the Italian transavantgarde and dadaism.

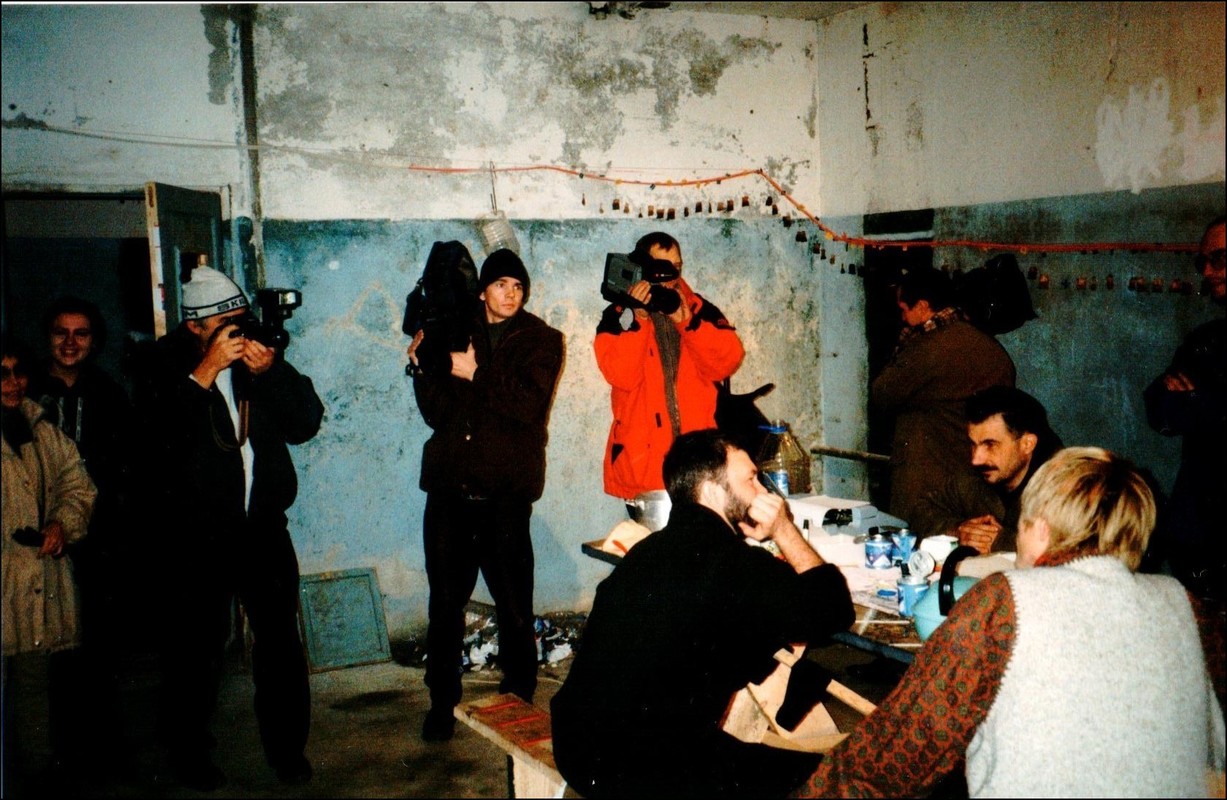

In 1999, the project Beyond Time Shelter was launched. Before the millennium there was discussion of the fact that in the year 2000 computers would stop working, planes would fall out of the sky, and there would be a catastrophe. The artists of Beyond Time Shelter decided to hide out in a bomb shelter. Which we did. It was an experiment in surviving in extreme conditions. We were an international team of 12 people: two were from Ljubljana, one from Poznan, one from Moscow, one from St. Petersburg, and seven from Novosibirsk. With no alcohol, no nicotine, no women, no equipment, no psychotropic substances, and no clocks. We were forced to spend three-and-a-half days “artistically” on plank beds dressed in padded jackets and felt boots.

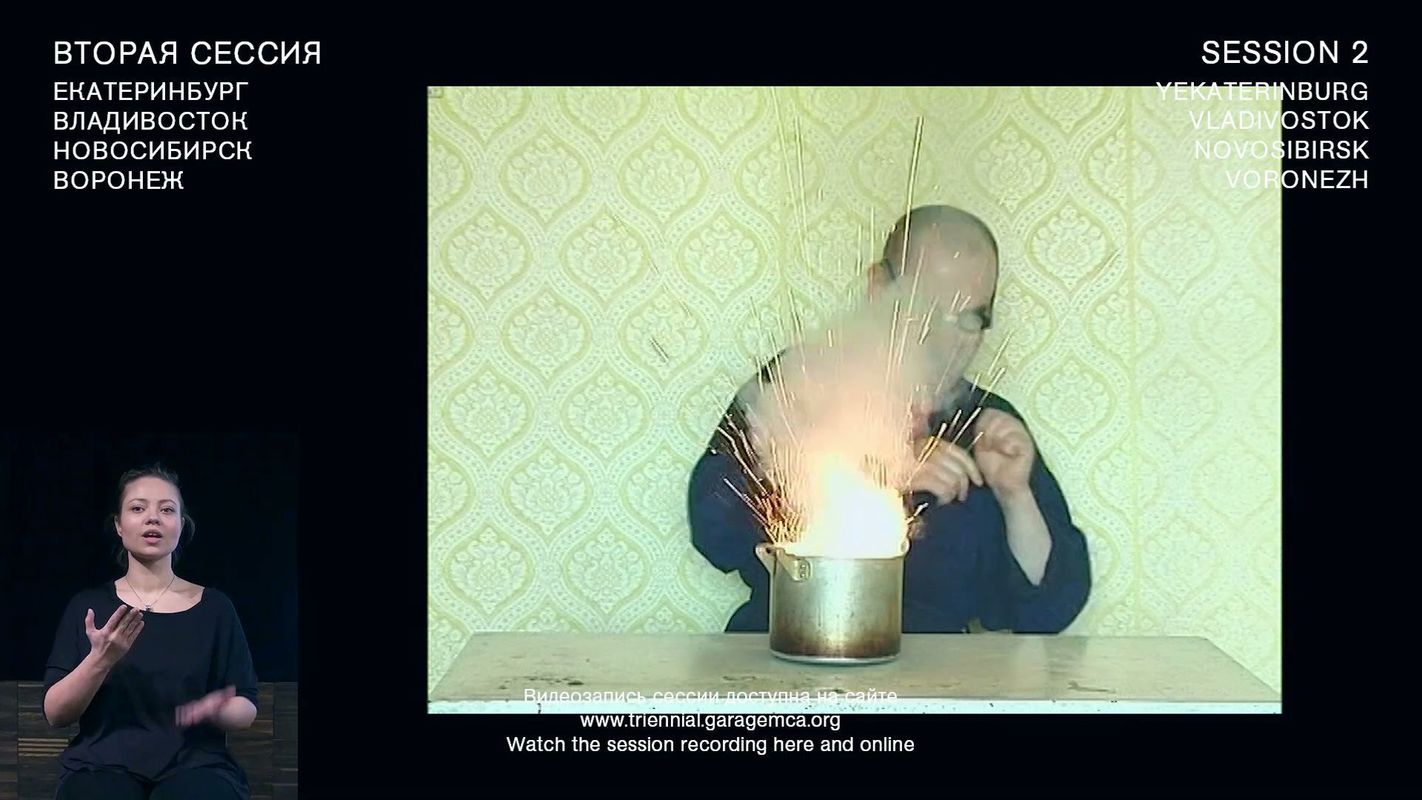

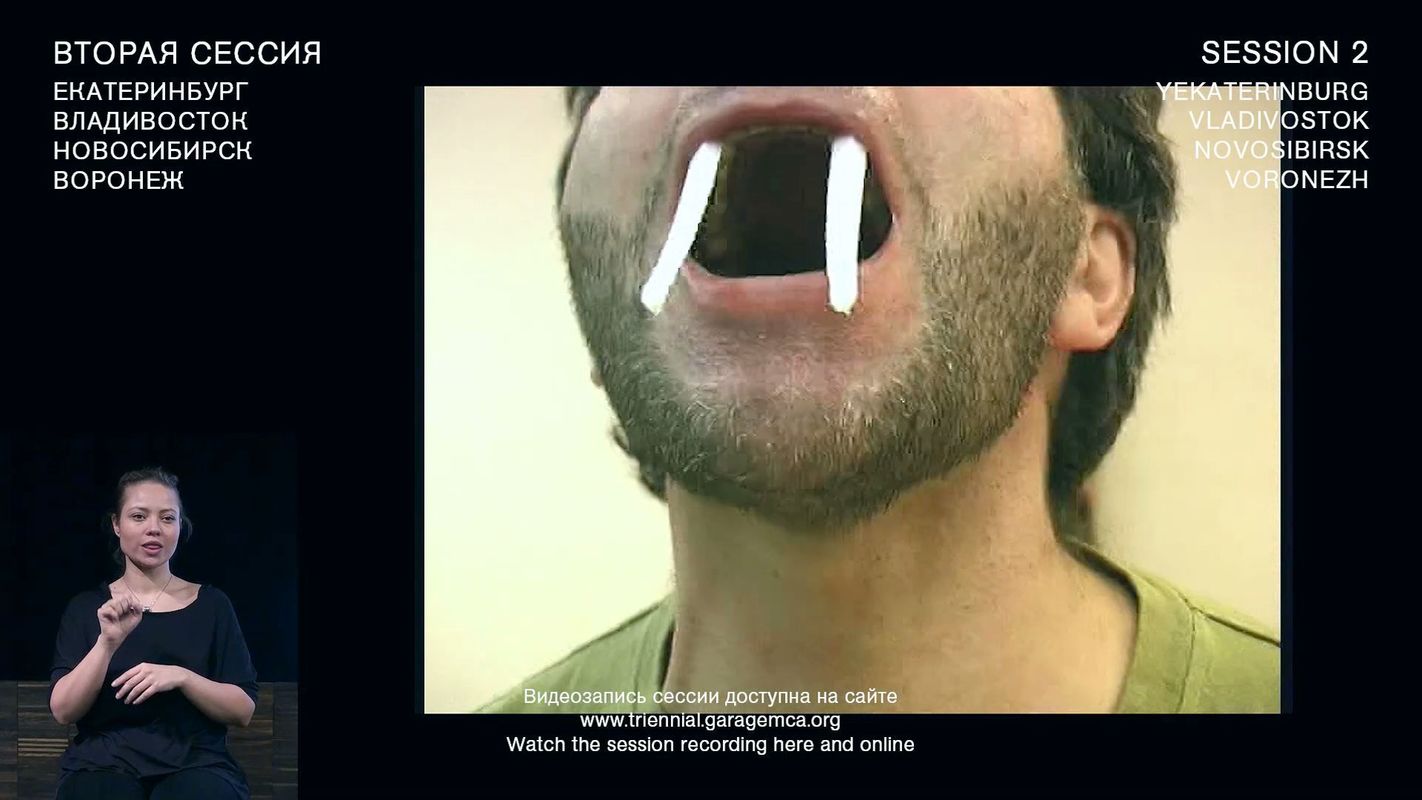

We had to entertain ourselves somehow. There were cameras and video cameras in the shelter [4]. Maxim Zonov filmed some rather amusing sketches and jokes. Some people made funny art objects. Everything was on a boyish level. Young people reverted to childhood and decided to have fun. That’s how the video Blue Noses Film 14 Performances in a Bunker was shot. And that’s where the group Blue Noses comes from. In my opinion, the strategy of “artistic idiotism” was thought up there: artists who present themselves as fools, which, of course, they are not. All of this happened under the aegis of Novosibirsk’s Yuri Kondratyuk Foundation. There was also support from international foundations.

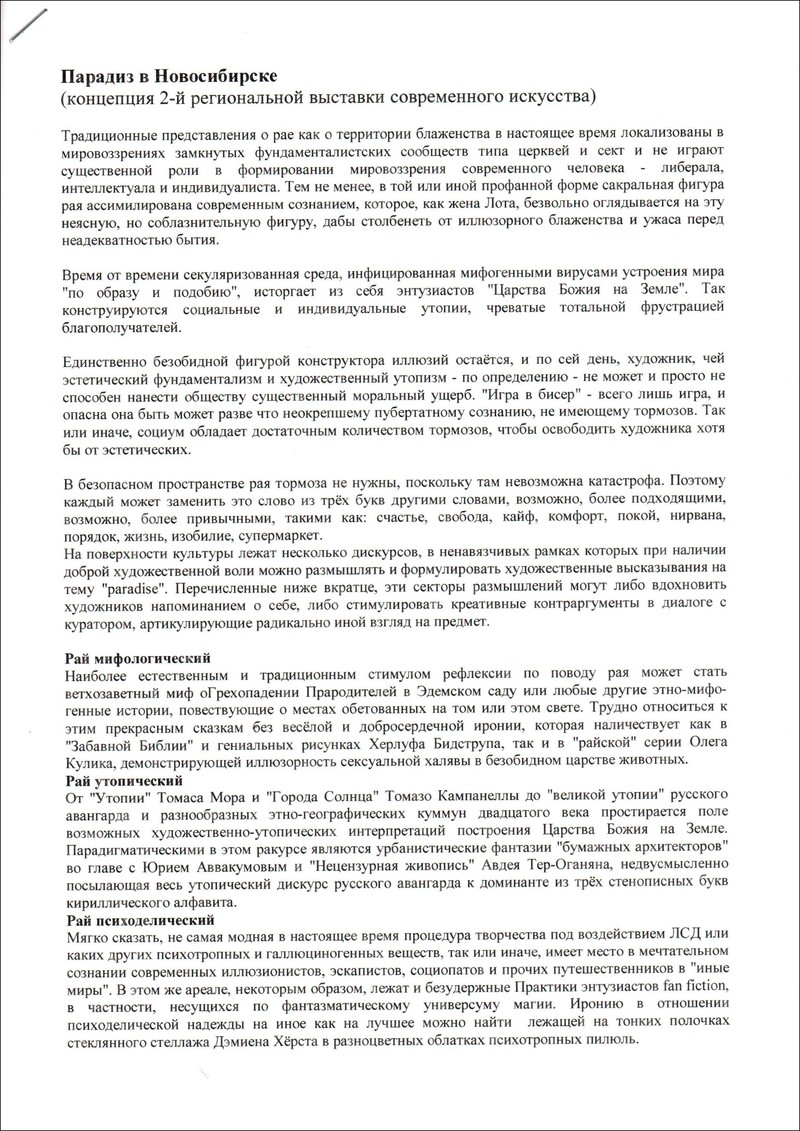

At that time the Kondratyuk Foundation launched a major project known as the New House of Culture. We wanted to change how houses of culture worked; they were places for knitting circles and various other decorative art activities. So we created our own house of culture, which organized monthly “big art Thursdays,” weekly “little art Thursdays”, and exhibitions like Fly!, Toys, Emergency Aid, Paradise in Novosibirsk, and Trash. This successful strategy was a great help in developing and promoting Blue Noses.

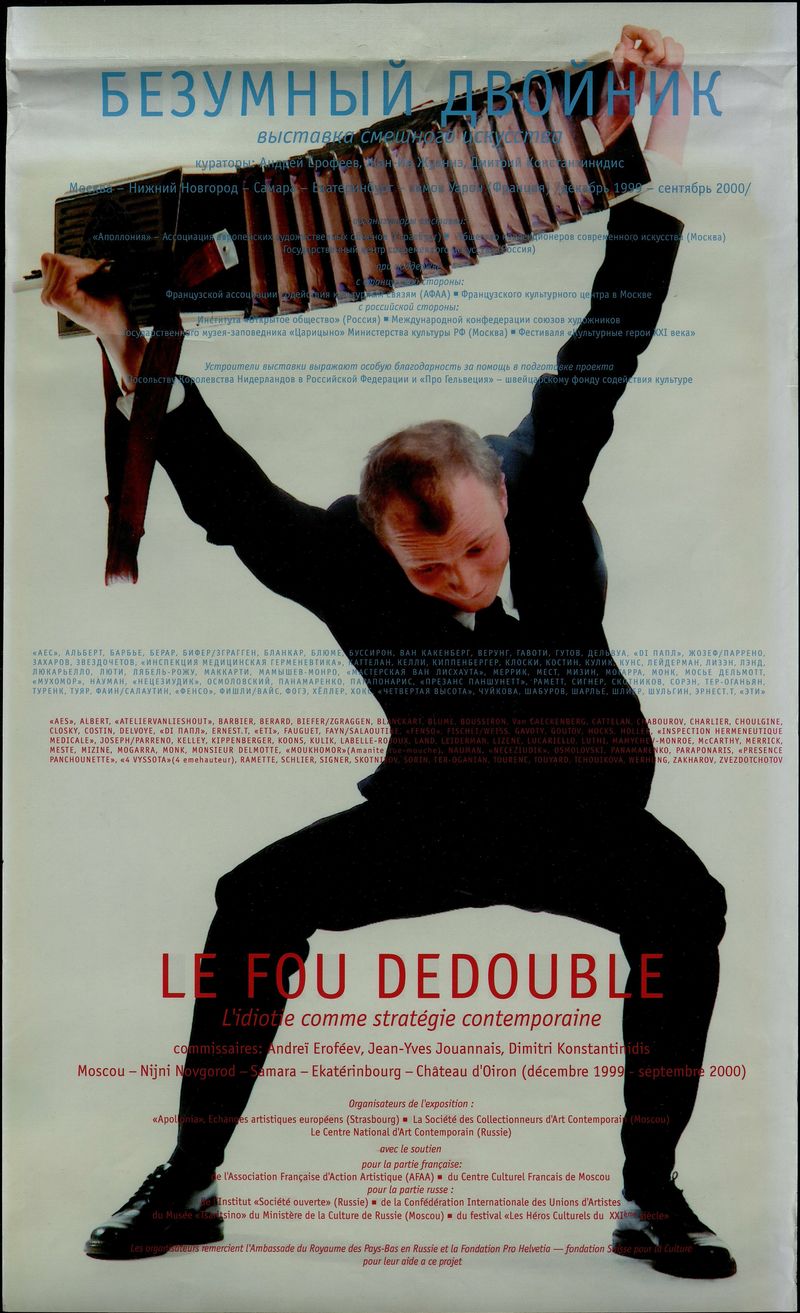

The ideology of Blue Noses and of many contemporary art figures in Novosibirsk is based on an original kind of mockery, the desire to take a joke too far and express one’s definitive opinion. The exhibition Crazy Double, which was curated by Andrei Erofeev [5] and took place in Moscow and Yekaterinburg, was a huge influence. It was based on the idea that the artist is a “healthy schizophrenic,” a split personality who is able to manage their schizophrenia. In their daily life the artist is an ordinary person, but when they create an artwork, they go beyond the boundaries of the existential, conventions, conditions, decency, and everything domestic.

We saw Blue Noses’ Video on the Knee as a kind of educational program: we gathered a group of students who wanted to make a funny video. We were tutors. The guys tried to make films and then we edited them together. Those masterclasses took place everywhere.

Then in 2004 Monstration became a powerful movement and a powerful brand, a free, poetic, mass Mayday parade with arbitrary, often absurd slogans. The leader of Monstration, Artyom Loskutov, is here today as a participant of the Triennial. Another of the artists behind Monstration is Maxim Neroda.

One might recall our poster, “Down with the Exploitation of Siberian Wildness in Art,” which was a godsend. At the right moment we understood that to exploit Siberian wildness was bad, simply inadequate. It was the view of some kind of really wild western curators, an outside view of Siberians. For some reason, respectable curators want to see Siberians as people in ushanka caps, in a state of wild intoxication.

In 2005, the Austrian artist Lukas Pusch visited Novosibirsk and we became friends. He organized a parade with paintings in the main street. Later, in 2008, we bought a motorcycle garage and placed it in the yard of my house, calling it White Cube Gallery. Lukas was charmed by the various strange constructions, from metal fences around residential buildings to garages. He had never seen anything like it in Europe and it seemed exotic. White Cube Gallery opened on August 22, 2008. One of the participants was a very interesting artist called Konstantin Eremenko. In his works he dreams up the history of Siberia as a place where life originated and where Jesus Christ was crucified.

This little garage functioned as a gallery for a year. On April 26, 2009, Artyom Loskutov organized the last exhibition there, which was about Monstration. And after that the repressions started.

Then we loaded the garage on a truck and set off for Mongolia. We got as far as the border, turned round, and traveled through the whole of Altai. The trip ended at Art Cologne. I arrived at the Koelnmesse and saw that our truck was parked there, like in Krasnoyarsk and Kosh-Agach.

The Siberian Center for Contemporary Art existed from 2010 to 2014. Today, little remains of contemporary art. A branch of the National Center for Contemporary Arts opened in the student town in Tomsk, and Vyacheslav Mizin became the director.

To conclude, I would like to show you the catalogue of the exhibition United States of Siberia. It took place in several cities, including Moscow and St. Petersburg. It included the most interesting contemporary artists from Novosibirk, the Omsk artist Damir Muratov, and the Krasnoyarsk artist Vasily Slonov.

1. Now Novosibirsk State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering.

2. Organized in 1985. The original group comprised Viktor Smyshlyaev, Andrei Kuznetsov, and Vyacheslav Mizin.

3. Existed from 1987 to 1991. The original group comprised Andrei Kuznetsov, Vyacheslav Mizin, Valery Klamm, and Aleksei Stepanov.

4. They were brought by Maxim Zonov.

5. The group exhibition Crazy Double / Le Fou dédoublé. L’idiotie comme stratégie contemporaine took place in Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Samara, Yekaterinburg, and Oiron (France) in 1999 and 2000. The curators were Andrei Erofeev, Dimitri Konstantinidis, and Jean-Yves Jouannais.