My father was born in a German settlement in Ukraine. My mother was from Lviv. They met in Yakutia-both had been sent there as “enemies of the people.” After Stalin’s death my father found his mother through the Red Cross. She lived in Karaganda and that’s where he moved with my mother in 1954. I was born there.

We had relatives in Germany and Canada, who had emigrated before the war. We could not keep in touch with them during the Stalinist repressions, but with the Khrushchev Thaw contact resumed. In 1956, my father first applied for permission to leave the country in order to rejoin the family in Germany. Of course, they did not let us go. During the two decades that followed, he kept trying to leave the Soviet Union. This came at a cost: he was threatened and humiliated at work and I was bullied as a student.

I had a strange childhood. We lived in the middle of the Kazakh steppe and my mother would tell me about the beautiful European city of Lviv with chestnuts in bloom and baroque churches. Meanwhile, my father would recall his childhood in the German settlement, with its cultural traditions, a local choir and orchestra, and his family’s huge private library. But I lived in the Soviet present, and my schoolteacher-a militant Stalin supporter-would tell me that my parents’ generation were young communists that came to Kazakhstan to cultivate virgin soil or mine coal in Magnitogorsk.

My father spent nights by the radio, listening to Deutsche Welle in his headphones. He was interested in the protection of human rights. My mother was a Catholic and she was interested in religious news, so she would listen to Radio Vatican. As I grew up, I started listening to the BBC, Radio Liberty, and Voice of America. I listened to jazz, rock-n-roll, and programs about contemporary painting, theater, and cinema. And so we passed on the headphones: father would listen to programs on politics, mom to religious news, and I listened to rock music. I also learned about the “Bulldozer Exhibition” from those “enemy voices,” as they called them.

It was only in the mid-1970s, thanks to the so-called eastern treaties signed by Leonid Brezhnev and Willy Brandt, we were allowed to move to West Germany. For me, everything in the West was interesting. I guess it was due to those years in which there was no access to information. I was especially interested in the lives of Soviet nonconformist artists-I knew about them from the same “enemy voices.” Some of the artists were already living in the West. A number of European art historians and Slavic scholars brought their paintings to the West and organized exhibitions for them. With every visit to such exhibitions I discovered a few new names. I was lucky to meet many artists, writers, and theater people from the Russian diaspora over the years that followed.

At university I had four semesters of art history, but I was studying documentary film. After graduating I worked as a freelance at West German television in Cologne, where I was an expert on Eastern Europe.

I had heard about Lev Kopelev before we moved to Germany. In 1975, he published the book To Be Preserved Forever and excerpts were read on Radio Liberty. I became interested in this man and his life. Towards the end of the 1970s, Heinrich Boll often spoke in defense of Russian dissident writers and I distinctly remember him saying, “My friend Lev Kopelev is in danger. They broke windows in his apartment; his phone was tapped and is now completely off. I cannot get through to him!”

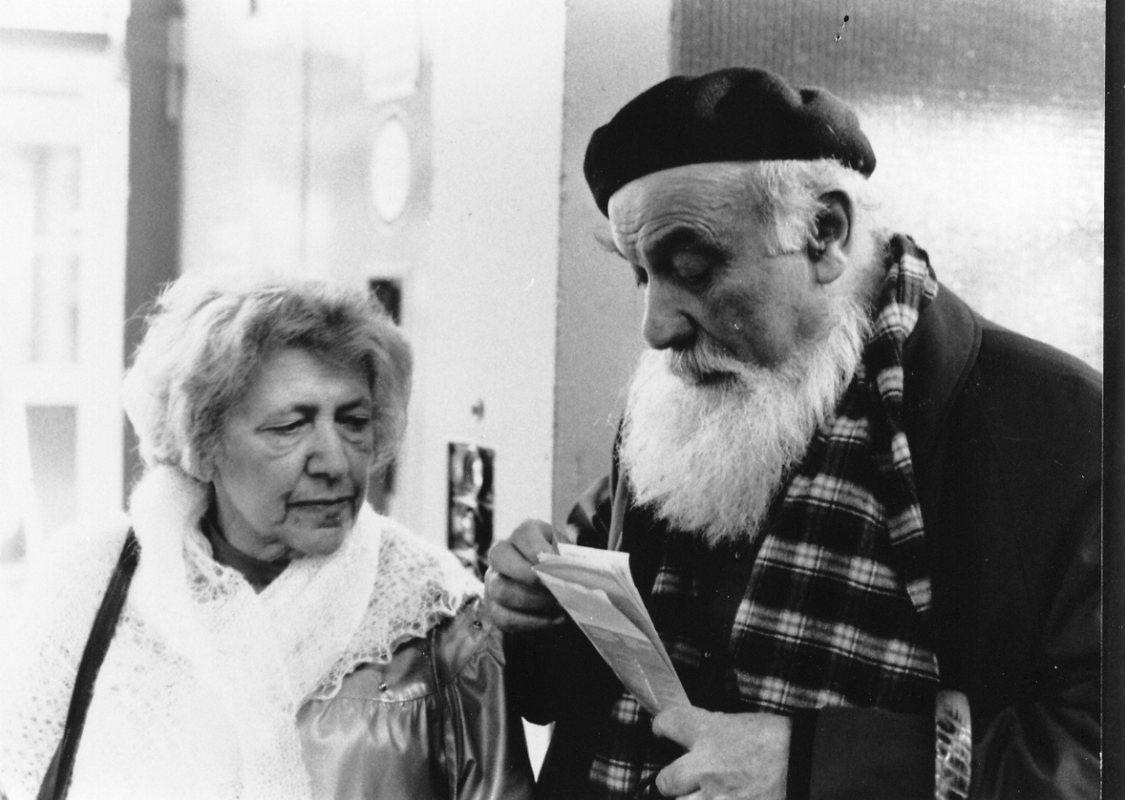

In November 1980, Kopelev was allowed to leave the Soviet Union. He and his wife came to stay with Boll in Cologne. In January 1981 they lost their Soviet citizenship. As resident of Cologne, Kopelev gave regular readings at literary evenings and meetings with students that I attended. He started a research project on the history of Russia-Germany relations-mutual understanding, images of friends and enemies-that came to be known as the Wuppertal Project (at the University of Wuppertal). I could really relate to that: in Karaganda, I was a German and was sometimes even called a fascist, but when we moved to Germany, I realized people always saw me as a Russian. Just asin the Soviet Union we did not know who we were, where we came from, and why we ended up in Kazakhstan, in Germany we still did not know who we were and why we had come. And then I see Kopelev announcing this project and saying that we should not politicize the relationship between Russian and German cultures, but we need to understand how they developed throughout history to overcome the hostility between them.

So I came up to him at one of those literary evenings and told him I was going to make my graduation film on that topic. That’s how we met. When he found out that I was working in television as a freelance, which meant no regular work, he asked me if I would like to become his personal archivist, and as he had agreed to bequeath his collection to the Research Center for East European Studies in Bremen. In 1989, the Center’s founder and director Wolfgang Eichwede offered me a contract, which was later renewed several times.

The archive of Lev Kopelev and Raisa Orlova is extraordinarily rich. Orlova studied American culture and was part of the editorial team at the journal Inostrannaya literatura [Foreign Literature]. In the 1940s, she maintained a correspondence with Lillian Hellman, met her in Moscow, and translated her works. She had her own Anglo-American circle, and Kopelev had his German one. Their flat in Cologne-the rooms, the corridors, the kitchen-was crammed with bookshelves and files. Working with their archive, I discovered a whole new world. It was like a mosaic that connected lives and events, time and space, and completed my idea of the scene I was interested in. Kopelev’s school was the best gift I could have been given. It taught me that we don’t need to narrow ourselves down to the constraints of our profession, that knowledge has no boundaries. When Kopelev passed away, I was among the executors of his will and transferred his archive to the University of Bremen according to his wishes. Then it seemed that episode in my life was over.

Years later, a woman who worked at the Research Center for East European Studies approached me at a conference on Boll and Kopelev that I helped organize and suggested that I apply for the position of archivist, which was then open. I agreed, although I had no qualification to work in an archive and had some doubts. That said, the documents in the archive were the very matter I had studied with Kopelev and dealt with at the TV station. I knew many people whose collections were included in the archive and the opportunity to share my knowledge of the subject, to provide commentary and context for those documents, was too tempting to turn down.

So, in 2012, I suddenly found myself heading the Russian section of the archive at the Research Center for East European Studies, which had previously been led by Gabriel Superfin and Galina Potapova. I cannot forget the huge responsibility that comes with this job.

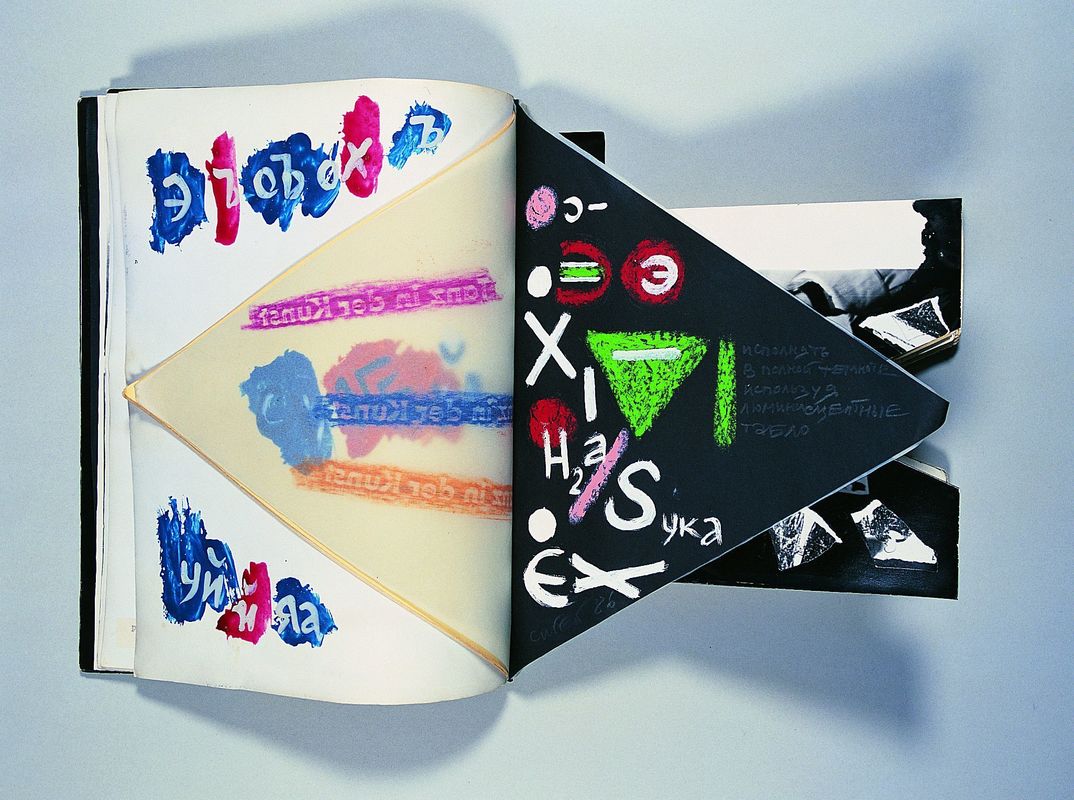

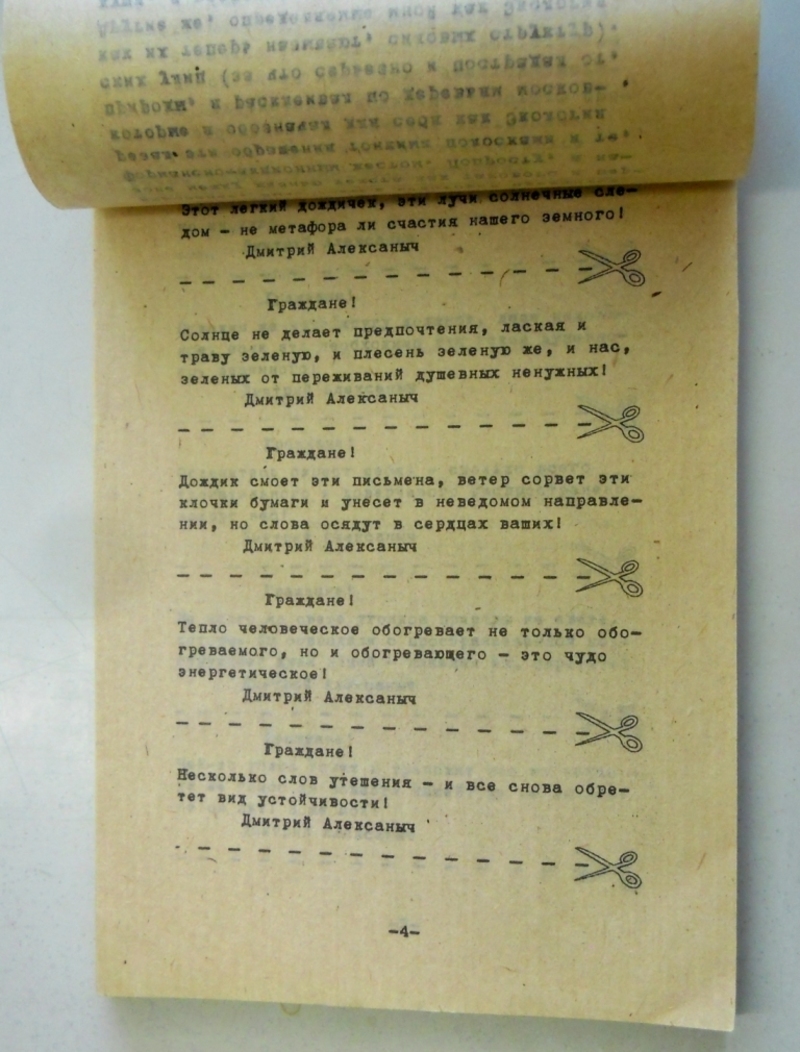

Since it was founded, the Center has accumulated a huge number of priceless archival materials. Today, our work is focused on classification and cataloguing of the archives and creating a clear and user-friendly structure. Materials relating to Soviet nonconformist art can be found in the archives of Sergei Sigov and Anna Tarshis, Boris Groys and Natalia Nikitin, Igor Golomshtok, Eduard Gorokhovsky, Henri Volokhonsky, Karl Eimermacher, and many other curators, poets, writers, and human rights activists.

Materials from the Research Center for East European Studies archive collection are scheduled to become available online from 2019.