In this article we will consider how the emergence of contemporary art institutions in the post-Soviet space entailed the necessity to produce new knowledge and educational models. We must limit ourselves to Moscow and St. Petersburg and the period of the 1990s because empirical research was localized in these cities in this period, but in future we hope to expand the geography and time of our research.

Part 1

In her thesis Leningrad/St. Petersburg Art of the 1980s–1990s. Transition Period[1] the art critic and curator Olesya Turkina suggested considering the period not as a gap between Soviet and post-Soviet reality involving a simple exchange of one idea of art for another or old institutions by new ones but as a transition in logic, representing the processual in the “here and now”. The transition, according to Turkina, is connected to a sense of “time transgressive” space, in which the continuity of the line connecting the past, present, and future is broken, or “multi-dimensional” time, when simultaneous overlapping of semiotic and “real” spaces occurs.[2] During the transition, former binary oppositions (official/unofficial, Soviet/Western, realistic/formal, etc.) blurred in favor of the simultaneous coexistence of numerous individual styles and trends. As Turkina writes, “in Leningrad during this period the transition was not from modernism to postmodernism but from art ‘relevant’ to the given place and time [. . .] to the time after time, i.e., to ‘postmodernity’, in which the relevance of innovation is not the main focus and is not predominant, and it is not the focus on the future that is important but the performativity of the event.”[3] In 1999, when Turkina wrote her thesis, the Moscow curator Viktor Misiano conceptualized a key concept for the 1990s—the tusovka[4] as a post-historical phenomenon, indifferent to prehistory and having the performative status of constant reproduction through a series of face-to-face meetings at various (near) artistic events.[5]

Such performative events, parties, and meetings as the main form of art production in the post-Soviet space of the 1990s were not unique but they were contemporary (maybe for the first time since the era of the Russian avant-garde) with the global turn in contemporary art of the late twentieth century toward community-based activity and relational aesthetics.[6] The Austrian art theorist Peter Weibel wrote that at this time art recognized the social context as a form: “Artists began to be decisively included in other discourses (ecology, ethnology, architecture, and politics), and the limits of art institutions were significantly expanded.”[7] This trend, which appeared in the Russian context in the late 1980s and early 1990s, was of a spontaneous, situational, life-creating nature because it was caused by the devaluation and disorientation of ideological and axiological foundations, the collapse of Soviet official institutions, and the irrelevance of previous educational and educational models. The boundaries of art practice radically opened out to the public space—on the streets, in squats, at the first artist-run galleries. The contemporary forms of artistic expression were actions, performances, exhibitions, events, dances, walks, and theater laboratories with an emphasis on live dialogue, game improvisation, bodily affectation, spontaneity, outrage, provocation, transgression, and subversion. In the art of the transition period, artistic initiation, the acquisition of new connections and the transfer of knowledge, pedagogy, and apprenticeship were of a syncretic nature and occurred in diverse, “swarm-like” (Gilles Deleuze), “unproductive” (Jean-Luc Nancy), “indescribable” (Maurice Blanchot) communities, ambivalently pulsating with enthusiastic energies of togetherness and infected with undesirable affects.

With the beginning of perestroika, the borders between the USSR and first world countries gradually opened up for ideas, people, things, and monetary transactions, promising yesterday’s unofficial artists freedom from political censorship and the administrative and bureaucratic apparatus. In 1989, after the first auction of contemporary art in the Soviet period (the so-called Russian Sotheby's), the free market and capitalism became the defining conditions for the development of a new post-Soviet art system. During the short period of the late 1980s and early 1990s in Moscow and Leningrad/St. Petersburg, a whole series of (para)educational initiatives arose from yesterday’s apartment seminars, clubs, and squats, Many of these self-organized institutions, coupled with spontaneity and creativity, had many years of experience interacting with the Soviet bureaucratic machine and had their own bureaucratic aesthetics (in the development of Moscow conceptualism[8]) and subversive bureaucratic enthusiasm (according to Olesya Turkina, in St. Petersburg “bureaucratization has become a kind of form of artistic activity”[9]). Left to their own devices, the artists of the late 1980s and early 1990s “dreamed up” bureaucracy by playing it: some according to new Western patterns, some according to the inertia of Soviet bureaucracy. So, when the first Western grant-giving institutions came to Russia along with global capital and the free market and the universities opened (Soros Foundation and John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation came to Moscow in 1992, Goethe Institute and Carnegie Moscow Center came in 1993, in 1994 the European University was founded in St. Petersburg, in 1995 the Moscow School for the Social and Economic Sciences (“Shaninka”) opened, and the Ford Foundation opened in 1996), Moscow artists, curators, art critics, and intellectuals were ready to get involved in the establishment of new platforms and educational initiatives. Universities and contemporary art centers opened, curatorial schools, media labs, and workshops were held. However, sometimes there were only one or several enthusiasts behind these conventional names; literally on their knees, in rather precarious conditions, they started the engine of the initial post-Soviet institutionalization, which also involved many paradoxes. In contradistinction to Western institutions, which appeared in the 1970s as subjects of resistance to commercialization, Russian institutions opposed themselves not to the capitalist method of “artistic reproduction, but rather [to [. . .] pre-existing institutions of power such as art academies, artists’ unions or museums.”[10]

The first example of such a paradoxical institution was the Center for Contemporary Art on Yakimanka, which emerged immediately after the August 1991 coup. CAC opened “in a complex of three low-rise buildings at the corner of Yakimanskaya Embankment and Dimitrova street (now Malaya Yakimanka). The idea to transfer these empty residential buildings to the management of the new institution belonged to the last Soviet city and regional authorities.”[11] The first artistic director and head of CAC was Leonid Bazhanov,[12] and Viktor Misiano was head from 1992. Like many at the time, Misiano was fascinated by the idea of community-based activities. CAC on Yakimanka became a commonwealth of the first Moscow galleries trying to form an art market and of numerous educational initiatives. Over the six years that CAC operated, its activities included a curatorial school,[13] the Visual Anthropology Workshop, Evgeny Asse’s laboratory at the Irina Korobina Architectural Gallery, the Free Academy of Boris Yukhananov, Nina Zaraetskaya’s Art Media Center TV Gallery, Irina Meglinskaya’s photography gallery Shkola, and studios of the most important artists of that time—Vladimir Kupriyanov, Dmitry Gutov, Yuri Leiderman, Gia Rigvava, and others. In 1994–1995 at CAC on Yakimanka a new media art laboratory with an extensive educational program opened with the support of the Soros Contemporary Art Center[14] (founded in 1992) and the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation.[15]

In 1992 art critic and curator Joseph Backstein, along with a group of artists and cultural workers close to the Moscow conceptualist circle, opened the Institute of Contemporary Art in the former studio of Ilya Kabakov at 6 Sretensky Boulevard. If in the early 1990s, according to one of the first ICA graduates, artist Viktor Alimpiev, the atmosphere at the institute was similar to a conceptualist circle,[16] by the 2000s ICA openly proclaimed its goal as being to introduce students to the context of the contemporary art process, including the theory and philosophy of art, and to instill the skills of project-based thinking, art management, and PR technologies.[17] In 1999, with the support of the Soros Contemporary Art Center (run by Irina Alpatova), ICA accepted its first cohort of students (including Viktor Alimpiev, Maxim Ilyukhin, and Elena Kovylina) for the educational course “New Artistic Strategies.”[18] In fact, ICA became the first Russian educational institution in the field of contemporary art, with its own exhibition, research, and publishing activities and a curriculum of theoretical and practical courses based on the Western model. In 1992, the Free Workshops School of Contemporary Art was founded,[19], which in 2000 became part of Moscow Museum of Modern Art. The Free Workshops did not produce as many big names as the ICA, but it continues to satisfy the demand of young people for art education evening classes.

The School of Contemporary Art created by the artist Avdei Ter-Oganyan in January 1997 as an art project stands out from this set of Moscow institutions. Today, this project might be called an artistic reaction to the almost complete absence of contemporary art education in Russia and also a parody of the Western institutional art models and critical discourse that now form part of the field of Russian contemporary art. The students of the school were Ter-Oganyan’s son David and his friends,[20] who had not even thought about making art before. Together they learned to make absurd and shocking performances, draw a black square, integrate into the art environment, overthrow the authorities of the art scene, literally lick the ass of the right people, and build a barricade from materials at hand.[21] Former student Maxim Karakulov recalls that it was primarily a collective project, “the participants of which agreed on the permanent reproduction of a particular activity, and only after that was it a ‘school’ in the direct sense of the word. And this is fundamental. The participants themselves acted as the material, and the tools were conversations, seminars, performances, everyday experiments, actions, theoretical and artistic texts, etc. There was no division between teachers and students. No one was endowed with a sense of superiority, nor was there anyone who was constantly placed in a situation of inferiority and lack. Everyone was an accomplice to a collectively produced event.”[22]

Ter-Oganyan parodied the very form of a school, exposing the contradictions of teaching contemporary art, where the creative impulse for the new, radicalism, and transgression is combined with the mechanisms of artistic institutionalization: influence, imitation, knowledge of the basics of individual success and career self-promotion. According to the art critic Julia Wolfson, “acting as a teacher, Ter-Oganyan remained primarily an artist of appropriation, building the entire educational process on direct repetitions of the creative methods of popular Western artists. So, the lesson on the work of Jasper Johns was built around the practice of drawing the American flag; in the lesson on Armand, students learned to flatten metal objects; in the lesson on Christo they practiced wrapping objects; on Malevich they learned to draw a black square; and in the lesson on performance they broke an alarm clock, hid in a chest, lay on two chairs or showed their naked ass.”[23]

Paradoxically, these appropriations, the reproductions of famous works, and the educational performances for spatial contextualization and collective bodily action[24] became contemporary art and went down in history. Barricade on Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street, which became the largest action in the history of post-Soviet art, grew out of the study assignment “How to Build a Barricade,” which marked the 30th anniversary of May 68 in France. Ter-Oganyan and his students made the props, banners, leaflets, and all the material parts. Anatoly Osmolovsky’s Non-Governmental Control Commission organized the action, and individual activists from various political movements and numerous art activist groups took part, including DvURAK, zAiBi, OsvoCH, Kilgore Trout Pioneers,and a group of students from the Grenoble School of Fine Arts that happened to be in Moscow. On May 23, 1998, in the center of Moscow, demonstrators built a barricade of empty cardboard boxes, construction debris, paintings by contemporary artists, road barriers, and tape and held it for almost two hours, shouting situationist slogans appropriated from the French. The last educational task of Ter-Oganyan’s school was the notorious action Young Atheist, organized on December 4, 1998 at the Art Manege art fair in Moscow. Ter-Oganyan came up with a price list with three options for the “desecration” of icons: by School students, by the customer on the spot or at home according to instructions.[25] The icons were cheap reproductions bought at the Sofrino factory shop, which specialized in the production of church ware. Participation in Young Atheist became the first and last unfulfilled task of the School, as none of the students wished to take part and the reproductions had to be chopped with an ax by the teacher himself. The action ended in a scandal; a criminal case was opened against Ter-Oganyan on charges of inciting religious hatred and the artist was forced to leave Russia for 20 years.

Part 2

In St. Petersburg in the 1990s the situation with art education was different. Despite the exhibition and creative activity, until the mid-1990s the city remained, as Olesya Turkina put it, a “cultural suburb” of both the West and Moscow.[26] The first educational communities— the Free University, Yuri Sobolev’s school, Timur Novikov’s New Academy of Fine Arts—were far from Western institutional forms of art education, turning instead, whether seriously or parodically, to models from the past (Soviet, avant-garde or even pre-modern). They bore traces of the universalism inherent in the Soviet educational project, as if trying to revitalize the prestige of science still lingering in the public consciousness.[27] But these first institutions tried to combine the ethos of common life, education, self-development, and therapeutic practices,[28] what Michel Foucault called “self-care” or the art of existence of neo-Pythagorean communities and Epicurean circles.[29]

The Free University,[30] founded in 1988 in Leningrad in the space of the Central Lecture Hall of the Znanie Society (42 Liteyny Prospekt),[31] consisted of creative workshops of painting (head Timur Novikov), theater (head Eric Goroshevsky), music (head Sergey Kuryokhin), film and video (heads Igor Aleynikov and Boris Yukhananov), literary criticism (head Olga Khrustaleva), and poetry (first head Dmitry Volchek, from 1989 Boris Ostanin). Poet and critic Aleksandr Skidan, who was then a student of the poetry workshop, recalled that the Free University “worked for free and based on principles of self-organization and was the culmination of the long history of Leningrad nonconformism, with its home seminars, samizdat magazines, apartment exhibitions, underground concerts and clubs, and relatively extensive social network.”[32] For another former student of the poetry section, poet and art theorist Dmitry Golynko, the Free University was important because of “the experience of a community, what Jean-Luc Nancy called a non-working community that produced idleness. The Free University produced knowledge as idleness, a communal form of leisure as an exchange of knowledge and experience. Importantly, it was not structured as a tusovka. But it was a painful experience, now it seems to be an experience of total precariousness, as something lost, unreproducible today.”[33] Within such an idle community, the idle body also produced a subject not yet infected with the neoliberal itch of productivity, existing as if in a gap between power and knowledge, a subject of counter-knowledge of the enlightenment utopia. Therefore, it is not surprising that as a fully functioning structure with a permanent platform for classes, the Free University existed for only two years until, in the wake of economic reforms, the Central Lecture Hall of the Znanie Society began to demand rent for the premises.

After that, the activity of individual departments and workshops either faded away or acquired institutional forms autonomous from the core of the Free University. The poetry workshop returned to the pre-perestroika format of the home seminar, from which it originally emerged. The last meetings after the fire in the St. Petersburg House of Writers were held in the Tolstoy House, in the room of one of the seminar participants. Having provided the impetus for a number of intellectuals to create individual biographies, the workshop remained poorly historicized, partly embodying its esoteric line in Dmitry Volchek’s Mitin Journal. The literary criticism workshop moved to the Lenfilm film studio, where the magazine Session appeared. Director and teacher Boris Yukhananov united the departments of theater, cinema, and video with the Moscow Free Academy in 1989. From them emerged the Workshop of Individual Directing and the group Teatr Teatr, where Yukhananov and many people from the new culture practiced an integral method of educating universal artists and personalities, syncretically combining painting and drawing, music and performance, cinema and video.[34]

In late 1989, the Painting Department of the Free University was transformed by Timur Novikov into the New Academy of Fine Arts, beginning to "function as a new education [. . .] with a new aesthetic concept.”[35] The New Academy was based in several rooms in a squat at Pushkinskaya, 10. It went over the head of the Soviet academy, which, according to Novikov, had degraded into a salon, to a past unspoilt by modernism and conceptualism. Novikov compared the New Academy to the Bologna Academy, founded by the Carracci brothers in Bologna at the end of the 16th century, implying the same performative gesture of rejection of the dominant aesthetic trends (conceptualism and neo-expressionism), in the same way that the Carraccis rejected Mannerism, and also laying the foundation within the academy of a special nepotism and closeness of students and teachers. The artist and New Academy member Andrei Khlobystin, in his book about 1990s St. Petersburg, Schizorevolution, writes: “Novikov revived the long-withered institution of apprenticeship in Leningrad. He called it the transmission of "parampara," which in Sanskrit means something like ‘from one to another’.”[36] This closeness, coupled with the Hellenistic cult of the body, meant literally getting used to the dandy, acting out everyday rituals—from wearing tailcoats, top hats, corsets, canes, lorgnettes, and velvet dresses or coats from Konstantin Goncharov’s[37] company Strogii Yunosha to attending ballets, reading lyrics by candlelight, and listening to classical music. A special kind of post-Soviet conservative queer subject was produced as a result of these dandy practices, a mixture of Oscar Wilde and Charles Baudelaire. Although the New Academicians did not see themselves in terms of queer theory, practicing “transvestism” somewhat spontaneously and even, as Khlobystin writes, driven by fashion. Philologist and art historian Maria Engström suggests considering neo-academism through queer optics, meaning not a special experience of identity and homosexual sensitivity but the artistic language to which neo-academism was addressed: “The New Academy of Fine Arts, founded by Novikov in 1989 in the city of Pyotr, Ilyich, Tchaikovsky (Oleg Kotelnikov), became the first queer community that addressed camp and neoclassicism as the language of Western conservatism and postmodern figurative art. [. . .] The complexity of the perception of neo-academism lies in its fundamental ambivalence, in the almost sadomasochistic tandem of tradition and transgression.”[38]

The Foucauldian conceptualization of ancient self-care techniques separated the latter from both sexualized and biopolitical understanding, insisting on self-care as a vital project of the interference of ethics and aesthetics. In this sense, the New Academy combined aesthetic, self-creating, and educational projects, where education is inseparable from the general ethos. Khlobystin writes: “The teachers of the New Academy, together with the students, created artworks, served each other as models, and made inventory and decorations from improvised materials. They led a joint life, shared meals, and supported each other financially: training at the New Academy was free, and no one received a salary. A plan to introduce corporal punishment for bad students did not find support, and the only one who was punished was [Vladislav] Mamyshev-Monroe, known for both his talents and debauchery.”[39] This episode of case of corporal punishment was staged and is allegorically documented in the film Poor Marks Again 2. Red Square or the Golden Section (1999), in which a professor of painting played by Timur Novikov whips the student Volodya, played by Mamyshev-Monroe, for drawing a “red square" in the classroom, thereby redirecting Vladimir toward the path to the ideals of beauty.

In summing up St. Petersburg art of the 1990s, Dmitry Golynko notes: “the aesthetic project of neo-academism seems to me to be a total conceptualization of the classical canon of beauty transferred to the register of contemporary art and left-wing, almost punk ideology. Strange as it may sound, neo-academism is not an ideological opponent of conceptualism but a radicalized offshoot. Firstly, it is a rather scathing satire on the bourgeois institutions of academic knowledge. It seems to declare: where you have hyper-bureaucratization with a continuous writing of synopses, we have a free bohemian brotherhood. Secondly, it is a utopian and therefore especially tempting attempt to defend an independent community free from both the old party-Soviet and the new bourgeois-liberal conjunctures. When looking at the cultural history of the 1990s, it is clear that this heroic attempt was largely successful.”[40]

However, looking back, we would rather note the historical doom and uniqueness of such syncretic institutions in their previous forms. Art education in the 2000s sought to differentiate the functions of education and training and was aimed at professionalizing the contemporary artist into a project manager filling out grant applications and meeting deadlines, and into a content provider regularly updating their CV and portfolio.

Part 3

In 2003 the first issue of Moscow Art Magazine was published and it was entirely dedicated to art education. The issue opened with a round table called “Who to teach? What to teach? And whether to teach at all...,”[41] involving Vladimir Kupriyanov, Evgeny Barabanov, Viktor Misiano, and Evgeny Asse (we note the gender balance characteristic of the time). Asking the questions, “Do modern art schools meet the challenges of the time? Do modern methods of teaching art cope with the blurring of the boundaries of artistic practice, with the convulsive change of its technologies and forms?,” teachers and artists agreed to various degrees that the era of dilettantism was over. The figure of the amateur, the “talented autodidact” required “when it is necessary to revolutionize the situation” (Misiano) or when “the situation itself encouraged the invasion of amateurs” (Barabanov) had played a renewing role after the destruction of the conservative system of Soviet art. Today, the system pushes amateurs to the periphery, it’s time for systematic art education.[42]

This watershed between the amateur artist and the in-demand artist with an education occurred in the same year that Russia joined the Bologna process. The introduction of the Bologna reform into the Russian educational system was aimed at accelerating Russia’s integration into the pan-European scientific and educational space, but immediately involved many problems due to the need to radically break down the previous—still Soviet—system in a short time, and transfer (sometimes mechanistically) American and European models without taking into account national specifics in the absence of technology for practical implementation.[43]

In Russia, educational reform coincided with the general growth of the economy (mainly due to high prices for exporting hydrocarbons), which led to an active expansion of the service sector and the cultural industry. In the 2000s, the first “swallows” of the emerging creative industry and knowledge economy appeared in Moscow, and a little later in St. Petersburg and a number of large cities. In 2004, the ARTStrelka cultural center opened on the territory of the former Red October confectionery factory; in 2005, the Fabrika Center for Creative Industries opened at the October Technical Paper Factory at Baumanskaya; in 2007, the first creative cluster appeared at a former wine factory, now the Winzavod Center for Contemporary Art, which not only united many galleries in one space but also offered its own educational program, studios, and workshops.[44] Artists integrated into the expanded field of art production, in which professional education began to play an increasingly important role. Accordingly, the transition from anarchic, situational art pedagogy and ephemeral institutions of the 1990s to the systematization and professionalization of art education was quite predictable.

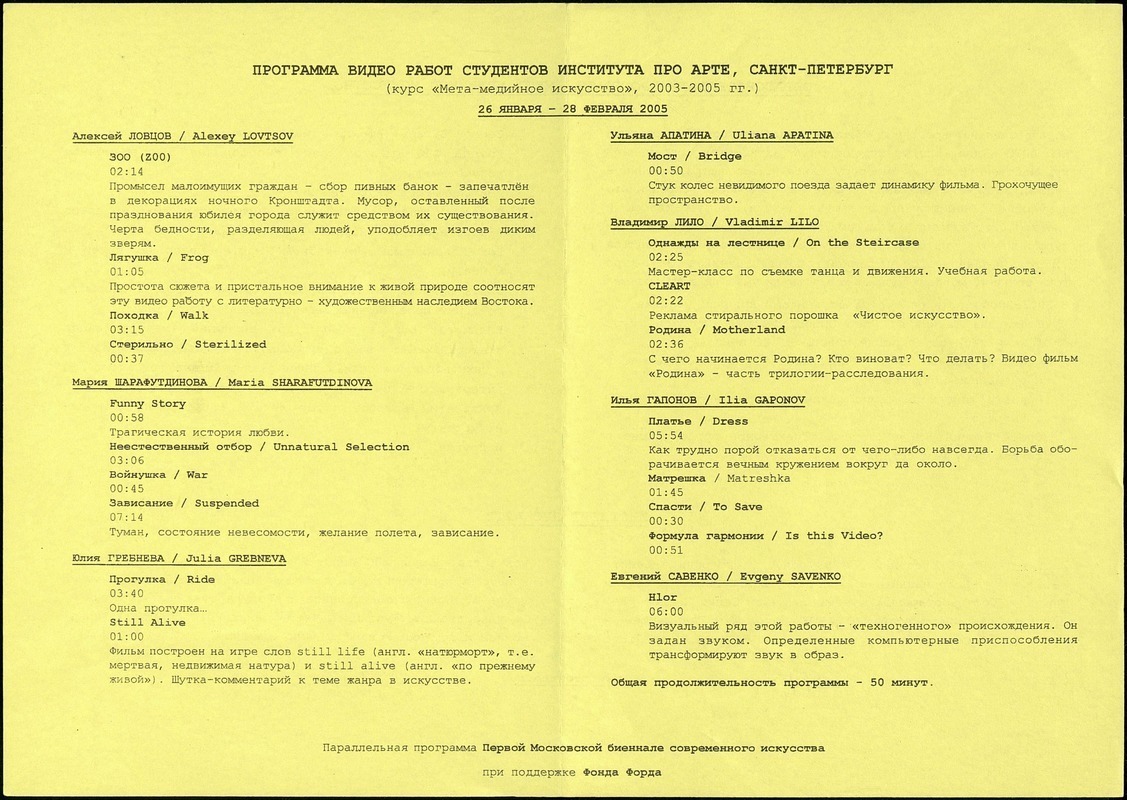

In 1999 in St. Petersburg, the PRO ARTE Foundation was founded with the support of the Soors Foundation. From 1997 to 2002 it functioned as a lecture hall[45] and in 2000 the School for Young Artists (SYA)[46] opened, which was the first educational institution for contemporary art in the north capital. The SYA educational program offered two years of training (without a state diploma) and became a hub institution, a model of professional adaptation within the system of contemporary art for artists with a classical/modernist background and graduates and students of art universities.[47] Despite the fact that SYA did not grow into an autonomous institution and remained an addition to other PRO ARTE projects, it became an important story for the city, producing more than 120 artists over almost 20 years of its, albeit irregular, existence. These artists would later became prominent actors within Russian contemporary art. In 1999/2000 the educational program Arts and Humanities was launched at St. Petersburg State University. It would later became a separate faculty with the informal name Smolny Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences. The institute was the first Russia to introduce the experimental model Artes Liberales, which proposed an individual approach to the formation of the curriculum, consisting of compulsory disciplines and interdisciplinary courses. Later, the Smolny Institute launched a master’s program for curators, critics, and artists. However, in the 1990s and 2000s in St. Petersburg there were no stable links between educational institutions of contemporary art and the creative industries. As Margarita Kuleva noted, St. Petersburg’s “contemporary art infrastructure was still in the process of formation, the agents of its development were mainly non-profit organizations and grassroots initiatives, and most of the financial resources and means of legitimization were at the disposal of institutions that developed in the pre-perestroika period.”[48] This, according to Kuleva, “significantly distinguished the St. Petersburg context from Moscow, where contemporary art was developing largely thanks to large investments from the private sector (Garage, Strelka Institute, ArtPlay, etc.).”[49]

A typical example is the Rodchenko Art School, which opened in 2006 as part of the municipal Multimedia Complex of Contemporary Arts (formerly Moscow House of Photography, now Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow), which was perhaps the first school in Russia created in the style of the Western art academy.[50] In the article “School Art,” art critic Alexandra Novozhenova wrote that a school of this format appeared in order to "produce new content for exhibition institutions, whose spatial capabilities at some point began to exceed the available turnover of artistic content.”[51] The artist’s function must be transformed from that of a manufacturer of individual artifacts for galleries into a multimedia content provider producing large-scale videos, installations, and custom design projects for the growing Moscow art infrastructure and the creative industry of the new Moscow urbanism. The model of the subject, which is produced at school as a young artist, becomes, according to Novozhenova, a side effect of project logic and the delivery of new content. The growing demand for education in the field of creative industries can also be explained by the appearance in 2003 in Moscow of the British Higher School of Design, which used the business model of the British School of Creative Arts (in the areas of Art and Design) and the Faculty of Business of Hertfordshire Business School (in the areas of Marketing and Advertising); as well as the appearance in 2009 on the site of the cultural center ARTStrelka of the non-profit Strelka Institute of Media, Architecture, and Design, founded by entrepreneur and philanthropist Alexander Mamut.

The educational models of the artist-bureaucrat and the artist-content provider that emerged in the 2000s were focused not so much on the closed morphology of the forms of the artwork as on an expanded international artistic field, and they required, along with the immanently artistic, increasing amounts of discursive and managerial skills. This will fully manifest itself in the form of epistemic interventions of contemporary art in all kinds of scientific discourses and educational practices. Knowledge is becoming more and more aestheticized and “executable,”[52] and education acquires the function of the "educational sublime.”[53] But art itself, borrowing its tools from knowledge, is transformed into "art as the production of knowledge" and "artistic research."[54] Artists become organizers of long-term research projects, take on administrative and discursive functions, receive academic degrees, conduct training courses in university departments or schools of supplementary education specially opened for this purpose[55].

In the recent article “When Knowledge Becomes Form”[56] (published in the magazine Theater in the section “Performing Knowledge” edited by Marina Israilova,[57] which explores how knowledge is performed in contemporary art, theater, dance, various pedagogical techniques, institutions, and various forms of social life), I wrote about the new demand for alternative forms of production of artistic knowledge and (self)entities looking for a way out of the traps of academic and institutional logic. Today, such seemingly bygone forms of knowledge production as apartment seminars, scientific and educational and poetry circles, secret laboratories, feminist reading groups, and training courses in semi-public studios and squats are gaining new popularity. These diverse beginnings have a similar focus to the generation of the 1990s on dialogue and communication, bodily and affective knowledge, community building, self-education, reassembly of their own subjectivity, and the inseparability of the ethical, aesthetic, and political. But there are a number of fundamental differences. Turning to radical pedagogy and the production of counter-knowledge, new independent art educational initiatives abandon the model of the artist as a medium, an unrecognized genius or demiurge, seeing themselves as precarious workers immersed in the analysis of specific institutional and political and economic conditions of the existing art system. In St. Petersburg, with its long history of uncensored resistance mentioned above, there are many such initiatives: Street University, the Chto Delat School of Involved Art and Rosa’s House of Culture, Paideiya School, the inclusive project Latitude and Longitude, the parody institute n i i c h e g o n e d e l a t, Studia 4.41 (now called Eto zdes’), Philosophic Café, Estestvennaya tsirkulyatsia, Noise Research Institute, queer/fem Laboratory of Writing and Sound Sound Relief, Maaimanloppu Science Theater, etc. They are not limited to criticizing neoliberal art and educational institutions, but as an affirmative program they offer various alternatives—from the radically politically engaged to the parodic, from inclusive to speculative—combining pedagogy with art activist practices and social work and expanding access to knowledge and education among unprivileged groups of people.

In connection with this new turn to the micropolitics of knowledge in art, I would like to mention another form of interaction between art and education that arose in the 1990s in St. Petersburg and is in demand today: the first St. Petersburg feminist organization “Cyber Femin Club.[58] Founded by Irina Aktuganova and Alla Mitrofanova in 1994 at Gallery 21 at Pushkinskaya 10, Cyber Femin Club largely outstripped the development of post-Soviet art and society. One of the first Russian examples of collaborative and participatory practices, the club was an artistic, art activist, educational, and social space, in which, in addition to exhibitions and conferences with a feminist agenda, practical DIY courses for women[59] and parties for subculture communities were held. People from different social groups met there—marginal communities, families of businessmen, people from neuropsychiatric clinics, children with autism spectrum disorder—and “staged theatrical productions or did craft activities under the guidance of a curator.”[60] The fact that Cyber Femin Club is included in the archives of large institutions calls not just for academic study but for active unarchiving. It is not surprising that a new generation of feminist activists, researchers, and artists are closely studying the experience of the first cyberfeminists for its emancipatory potential and transformative attitude toward art, technology, knowledge, and everyday life. Alexandra Shestakova noted in the article “Transform Knowledge” that the historicization of practices destabilizing the monopoly of normalized knowledge, creating "previously unimaginable generalities, rationality, and futurity" should begin with Cyber Femin Club, since it "created intermediate networks extending far beyond the existing boundaries of art.”[61] Cyberfeminist methodological and pedagogical attitudes towardsopenness to any—including non-artistic— experience, a bet on the network logic of the community, and the use of new media and technologies for liberation from gender, bodily, political, and epistemological subordination are being reactualized today in projects such as the Cyberfeminism telegram channel,[62] under the auspices of which, in 2020, the symposium Post-Cyberfeminism was held at Rosa’s House of Culture (St. Petersburg), as was an exhibition of post-cyberfeminist art which referred directly to Cyber Femin Club.

[1] Olesya Turkina, Iskusstvo Leningrada/Sankt-Peterburga 1980–1990-kh godov, candidate’s diss., (St. Petersburg: State Russian Museum,1999).

[2] Ibid.,6.

[3] Ibid., 7–8.

[4] Viktor Misiano, “Kulturnye protivorechiia tusovki,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/76/article/1658

[5] At the same time there were tangible differences between the St. Petersburg situation and that in Moscow: a lack of a market for contemporary art and Western art programs, strong modernist traditions, and an attitude of selflessness and decadence. Instead of the figure of a party-goer as a body reproducing a ritual of meetings in anticipation of a potential conversion of symbolic capital, the St. Petersburg communities of the 1990s produced a dandy body or a cynical body, where life itself became a work, and the subject simultaneously self-created and self-destructed on the transgressive front of free love, raves, drugs, and cross-dressing.

[6] In Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics the place of the art object is occupied by the relations between people themselves and the surrounding social context: “So, meetings, dates, demonstrations, various types of cooperation between people, games, holidays, places of cohabitation—in short, a set of methods of meeting and constituting relations today are aesthetic objects, amenable to self-valuable development.” Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics. Post-Production, (Мoscow: Ad Marginem Press, 2016), 12.

[7] Peter Weibel, “Contextual Art: Toward the Social Construction of Art,” Theory and Practice, http://special.theoryandpractice.ru/peter-weibel

[8] Bureaucratic languages and bureaucracy as a form of production and documentation of art were handled differently by Yuri Albert, Ilya Kabakov, Dmitry Prigov, the group Collective Actions and Andrei Monsatyrsky, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, and others. See Moskovskii kontseptualizm. Nachalo (Nizhny Novgorod: Volga Branch of the National Center for Contemporary Arts, 2014).

[9] “The principles of the ‘heavenly hierarchy’ were most clearly manifested in the 1990s in the New Academy of Fine Arts founded by Timur Novikov with the appointment of professors of the New Academy (Andrei Medvedev, Denis Egelsky, Georgy Guryanov, Egor Ostrov, Stanislav Makarov, Oleg Maslov, Viktor Kuznetsov, Olga Tobreluts, Joulia Strauss, and others), the Scientific Secretary of the New Academy (Andrei Khlobystin), the Director of the New Academy Museum (Viktor Kuznetsov), and the annual awarding of honorary diplomas. Deprived of the burden of real (= political, economic) power, St. Petersburg seemed to lose bureaucratic mechanisms in cultural life. Symbolic values did not compensate the city for the loss of its capital status in the twentieth century. However, in the era of decentralization and total aestheticization, these values are in demand in gaining the identity that a person is losing.” Olesya Turkina, “Neofitsial’naia li stolitsa Sankt-Peterburg?,” Gif.ru, http://www.gif.ru/texts/txt-turkina-neo-li

[10] Viktor Mazin and Olesya Turkina, “Lov pereletnykh oznachaiuschikh v institute sovremennogo iskusstva,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/76/article/1656

[11] See the information about the Contemporary Art Center on the website of the Russian Art Archive Network: https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/organization/OHYV

[12] Several years after leaving CAC at Yakimanka, Leonid Bazhanov initiated the creation of the National Center for Contemporary Arts, which launched in August 1994 and by the end of the 1990s had become a network organization with branches in St. Petersburg (1995), Kaliningrad (1997), Nizhny Novgorod (1997), and Yekaterinburg (1999). Among the main activities of the NCCA were education and research in the field of contemporary art (lectures, seminars, masterclasses).

[13] In 1993 Viktor Misiano, in parallel with the Workshop of Visual Anthropology, ran a curatorial school, devised, according to him, “to finally codify and legitimize the curator as a profession. This was bold and provocative, since the term still jarred with many due to its associations with KGB curators” (from Roman Osminkin’s conversation with Victor Misiano, November 2020). But from the perspective of 2017, this first experience of curatorial education is seen by Misiano as an exception: “The funds and enthusiasm of the organization were enough for only two iterations. And as the authors of the course noted, graduates at that time ‘had, in fact, nowhere to work.’ After which there was a long pause.” Victor Misiano, “Institutsiia kuratorstva v Rossii. Zametki na poliakh edva li slozhivsheisia professii,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/55/article/1116

[14] The Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Moscow was founded in fall 1992. It was part of the Soros network of contemporary art centers operating in Central and Eastern Europe. Educational projects were an important part of its activities. The Moscow Center was headed by art historians Irina Alpatova and Vladimir Levashov. See the information about the Soros Center for Contemporary Art on the website of the Russian Art Archive Network: https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/organization/OHHQ

[15] Among the teachers who conducted practical classes, lectures, and seminars were “well-known Western authorities in the field of the art of new technologies—Ange Leccia, Louis Becke (France), Lev Manovich (USA), Kluszczynski Ryszard (Poland), Kathy Rae Huffman (Canada), Maia Giacobbe Borelli (Italy), as well as our compatriots—the artists Sergei Shutov and Nicola Ovchinnikov, Nina Zaretskaya (TV Gallery), Tatyana Didenko (Tishina #9), and others. Among the topics proposed for discussion were ‘Cinema and electronic technologies,’ ‘Video,’ ‘Computer technology and multimedia,’ ‘Virtual reality,’ ‘Sound,’ ‘Light,’ ‘Space,’ ‘The problem of production, interpretation ,and distribution’.” Mikhail Bode, “Otkrytie laboratorii novykh media. Novye tehnologii iskusstva gotoviatsia k svoemu rastsvetu,” Kommersant, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/71269

[16] Timeline: “IPSI. Kratkaia istoriia problem sovremennogo iskusstva,” Look at Me, http://www.lookatme.ru/mag/live/industry-research/193399-ipsi-timeline.

[17] A substantial report on the activities of Art Projects Foundation. November 2000–August 2001. Garage Archive Collection

[18] See, for example, the list of participants of the exhibition of the first cohort of ICA students, The Last Generation: https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/event/ENKZ

[19] See the information about the Free Workshops School on the website of Moscow Museum of Modern Art: http://www.mmoma.ru/school/about

[20] Participants: Ilya Budraitskis, Pyotr Bystrov, Aleksandra Galkina, Anton Karakulov, Maksim Karakulov, Mikhail Mistetsky, David Ter-Oganyan, Valery Chtak, and others.

[21] “But we started calling ourselves that (artists) only after shooting the video Get Out of Art! (February 1998), during which we learned to integrate into the art environment. As you know, for this you need to be able to overthrow established authorities, thereby clearing your way and declaring yourself. […] In the process of “insulting prominent representatives” of the Moscow art environment, the conceptual snobbery of Yuri Albert, the abstract romanticism of Yuri Zlotnikov, and the quasi-animosity of Oleg Kulik were paradoxically revealed. And for this, numerous lectures and historical reviews were not needed. The problems of contemporary artistic creativity were more fundamental and arose from direct conflicts during communication. The old strategy of the avant-garde opposition to the established artistic system gave an unexpected result. They paid attention to us, and we really began to integrate into the Moscow art environment.” Maksim Karakulov, “Shkola sovremennogo iskusstva protiv vsekh. Popytka reprezentatsii,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/80/article/1748

[22] Ibid.

[23] Julia Wolfson, “Avdei Ter-Oganyan: dvoinoe zaimstvovanie,” https://j-volfson.livejournal.com/34764.html

[24] Radek Group, which emerged from the depths of Ter-Oganyan's school, continued the form of collective bodily action and the exploration of the boundaries of collectivity and bodily solidarity. In one of their actions, Hunger Strike Without Making Demands, which ran over four days in June 2003, the artists explored the feeling of hunger as such, which could only be comprehended by being hungry. The artists did not just bring an existential question about the limits of their existence into the field of art but gained bodily knowledge about hunger in isolation from the stable political pragmatics attached to the hunger strike as a form of protest. See “Interview with Radek Group” on the website of the Russian Art Archive Network (https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/document/V1571) and A. Penzin, “Psikhoanaliz form protesta,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://xz.gif.ru/numbers/53/formy-protesta

[25] Vesna Cvetkovic, “Proba topora ili agoniia ‘avtoritetov’,” Zavtra, https://zavtra.ru/blogs/1999-04-2081

[26] “In Leningrad/St. Petersburg, despite the fact that, at first glance, the so-called art market has not yet developed (there was no network of galleries or extensive information base), there are active museums (mainly the State Russian Museum, the initiative of which for the development of contemporary art has been taken up by the State Hermitage Museum in recent years, and by the State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg, the Russian Ethnographic Museum, and the Manege Central Exhibition Hall, where exhibitions of contemporary art are regularly organized), non-profit galleries and centers (for example, the Cultural Center Pushkinskaya 10), curators, and artists. However, until the mid-1990s Leningrad/St. Petersburg remained a ‘cultural suburb’ for both external (Western) and internal (Moscow) critics. One of the reasons lies not only in the faster ‘colonization’ of the Moscow art market but also in the essential difference between Moscow and St. Petersburg contemporary art, which was aptly defined by Viktor Tupitsyn as "the aesthetics of transparency (Moscow visual paradigm) in contrast to the aesthetics of the blind spot (in the case of St. Petersburg).” Olesya Turkina, Iskusstvo Leningrada/Sankt-Peterburga 1980–1990-kh godov, 17.

[27] Here it is also worth noting the largely selfless educational activities of such figures as Ivan Chechot, Ekaterina Andreeva, Alla Mitrofanova, Arkady Dragomoshchenko, Viktor Mazin, Olesya Turkina, Vasily Kondratiev, and others in organizing and conducting the first lectures and courses (which had a great influence on young artists), thanks to which the gaps accumulated during the Soviet period in the history and theory of contemporary art were largely filled. Ivan Chechot lectured at the Russian Institute of Art History and the lecture hall of the Russian Museum in the 1990s, and Ekaterina Andreeva introduced the first courses on contemporary art in the field of official education. Andreeva recalls: “In 1999, Ivan Dmitrievich Chechot invited me to present a course at the new European University (where I ran a series of lectures on nonconformism), and in 2000 he managed to introduce his brainchild, Smolny [Smolny Faculty of Liberal Sciences], to St. Petersburg State University and invited me to lecture there. In the building on Vasilievsky I gave two courses, ‘Contemporary Art as a Problem’ and one on Russian nonconformism of the 1940s–1980s. Someone gave the former course based on my program for a number of years afterwards” (from personal correspondence between Roman Osminkin and Ekaterina Andreeva, May 2020).

[28] Among these organizations, the school of Yuri Sobolev and Mikhail Khusid in Tsarskoe Selo stands apart. It was a place where friendship, cooperation, and apprenticeship were closely intertwined yet was grounded on the figure of a Teacher who literally cared about his students not only as artists but also as individuals, and also actively used psychotechnical techniques and training. For more details, see: Elizaveta Morozova, “O shkole Soboleva i zavarke,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/58/article/1179.

[29] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, volume III: Care for the Self (Kiev: Dukh i litera; Grunt; Мoscow: Refl-buk, 1998), 52–63.

[30] O.N. Ansberg and A.D. Margolis (eds.), Obschestvennaia zhizn Leningrada v gody perestroiki. 1985–1991 (St. Petersburg: Serebryannyi vek, 2009), 136.

[31] “The Leningrad section of the Znanie (Knowledge) Society was the largest in the USSR. In various years it had between 20,000 to 48,000 members. From the 1960s through the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of lectures were delivered to the people of the region. Almost every resident of Leningrad attended lectures at the Central Lecture Hall, the Hermitage, the Russian Museum, the Leningrad Philharmonic, and the Planetarium on more than one occasion. At this time, more than 1,000 people's universities were in operation and a system of legal and economic universal education was developed. Leningrad lecturers gave lecture series all over the country, from Sakhalin to Kaliningrad” (https://znanie.spb.ru/history).

[32] An evening at ABCenter, dedicated to the Free University (St. Petersburg; 1988–1991), January 19, 2018, https://youtu.be/CMKdLS4qQXw

[33] Ibid.

[34] See A Pavlenko, “Masterskaia individualnoi rezhissury “MIR”, https://borisyukhananov.ru/worlds/?id=1&fbclid=IwAR35wc4Ifm_FO5N4_ImSELWyAu6JSmztEumfpOXBFVqrFkb6hQ1jsEkYUL8

[35] Timur Novikov, “Peterburgskoe iskusstvo1990-kh godov,” Lectures (St. Petersburg: Gallery D137; New Academy of Fine Arts, 2003), 36–37.

[36] Andrei Khlobystin, Shizorevoliutsiia. Ocherki peterburgskoi kul’tury vtoroi poloviny XX veka (St. Petersburg: Borei Art, 2017), 141.

[37] Maria Udovydchenko, Konstantin Goncharov i Galereia mody ‘Strogii Iunosha’,” Russian Art Archive Network, https://russianartarchive.net/ru/research/konstantin-goncharov-and-the-strict-young-man-fashion-gallery

[38] Maria Engström, “Metamodernizm i postsovetskii konservativnyi avangard: Novaia akademiia Timura Novikova,” Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 3, 2018, 264.

[39] Andrei Khlobystin, Shizorevoliutsiia, 164–165.

[40] Dmitry Golynko-Volfson, “Strategiia i politika vsego novogo. Kak segodnya pisat’ kontseptual’nuiu biografiiu Timura Novikova i peterburgskogo iskusstva 90-kh,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://xz.gif.ru/numbers/70/golynko-timur

[41] Vladimir Kupriyanov, Evgeny Barabanov, Victor Misiano, and Evgeny Asse, “Who to teach? What to teach? And whether to teach at all... Round table,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/58/article/1172.

[42] Ibid.

[43] R.V. Kupriyanov, A.A. Vilensky, N.E. Kupriyanova, “The Bologna process in Russia: specifics and difficulties of implementation,” Bulletin of the Kazan Institute of Technology, 20, 2014, 412.

[44] “The largest one in Moscow today is ARTPLAY Design Center. A number of educational institutions are located there, including the British Higher School of Design, the Moscow School of Cinema, and Moscow Architecture School." A.I. Gretchenko, N.A. Kaverina, and A.A. Gretchenko “Sovremennoe razvitie kreativnykh industrii v Rossii (opyt stolitsy I regionov),” Vestnik SGSEU, 1, 2019, 58–65.

[45] Digitized video recordings of lectures by Ivan Chechot, Olesya Turkina, Arkady Ippolitov, Alexander Borovsky, Ekaterina Degot, Viktor Mazin, Gleb Ershov, and other art critics who lectured at PRO ARTE from 1997 through 2002 are available online: https://vimeo.com/showcase/6929039.

[46] School for Young Artists, https://proarte.ru/projects/art.

[47] “Analysis of secondary data from the PRO ARTE alumni database over the past 6 years has shown that the school is primarily focused on working with artists who have received a modernist/classical education: out of 100 graduates of the last 6 years, more than 4/5 graduated from classical art universities, more than half of graduates previously studied at the Stieglitz Academy.” M.I. Kuleva, “Sovremennoe iskusstvo kak professsiia: kar’ernye puti molodykh khdozhnikov s raznym obrazovatel’nym bekgraundom (sluchai Sankt-Peterburga,” Zhurnal sotsiologii i sotsial’noi antropologii, 1, XIX, 121.

[48] Ibid., 115.

[49] Ibid.

[50] We note that the educational models of conventional Western art academies vary from Scandinavian state socialism to American neoliberalism. Most Scandinavian art academies, unlike the classically neoliberal American ones, do not so much produce individual artists for the art market as model ideal “project managers of the future," artist-bureaucrats, team researchers, and communicative designers embedded in the system of state institutions and the social sphere. See more on this trend: Ane Hjort Gutt, “The End of Art Education as We Know It,” https://kunstkritikk.com/the-end-of-art-education-as-we-know-it

[51] Alexandra Novozhenova, “Shkolnoe iskusstvo,” Colta.ru, https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/2020-shkolnoe-iskusstvo.

[52] “Over the past few years, discourse has also dominated artistic practices: a masterclass is followed by a symposium, followed by a round table, followed by a conference, then something called a ‘workshop’ or parody training, lectures and their cycles, literary and poetic evenings, Marxist circles, reading groups, film screenings with discussions, forums, performances, excursions, and others.” Egor Sofronov, “Ispolnyat’ znanie,” Almanac MediaUdar II (Мoscow: MediaUdar, 2016), 152.

[53] “Surprisingly, this tandem of contemporary art and theory aestheticizes the latter, giving the theory a dimension of artistic attractiveness. Yet contemporary art is considered a special field where critical theory is instrumentalized. It plays the role of a necessary competence for artists and critics. If critical theory is needed to understand and, importantly, work in the field of contemporary art, then it is tempting to reduce the latter to servicing the autonomy of the institute of art. I call this process ‘the educational sublime.’ It is a situation in which a lecture, reading group or seminar is endowed with aesthetic qualities and judged based on taste, while remaining separate from the everyday life of students. There is something like a performance of knowledge, where the student becomes a passive consumer of the aesthetics of theory.” Boris Klyushnikov, “Kommentarii k perevodu lektsii Alena Bad’iu ‘Sub”ekt iskusstva’,” Termit. Bulletin of Art Criticism, https://labs.winzavod.ru/bulletin-criticism

[54] “In the last decade, discussions on the topic of artistic research and art as knowledge production have filled both art criticism periodicals and academic art history literature. Since the beginning of the noughties, countless symposiums, conferences, exhibitions, and seminars have been held on this issue. There are not only individual grant programs that finance ‘artistic research’ projects but also entire institutes, art residencies, periodicals, and other institutional entities that programmatically position themselves as centers for artistic research’.” Liudmila Voropai, “‘Khudozhestvennoe issledovanie’ kak symptom: o meste khudozhnika v ‘kognitivnom kapitalizme,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/6/article/55

[55]The downside of this process is the increase in bureaucratization, including in the field of art education. As Mark Fisher convincingly showed in one of the chapters of his book Capitalist Realism, over the past 30 years, the education sector, contrary to the promises of neoliberalism, has not just acquired a flexible and decentralized "business ontology" but has become even more bureaucratized into a system of constant audits, monitoring, performance indicators, reports ,and self-promotion. See: Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (Мoscow: Ultracultura 2.0, 2010), 73.

[56] Roman Osminkin, “Kogda znanie stanovitsia formoi,” Teatr, 44, 2020, 161.

[57] Levaia ideia: vzgliad iznutri. Blok Mariny Israilovoi, Teatr, 44, 2020, 144.

[58] “The first international feminist conferences and round tables, thematic exhibitions, performances and concerts, media projects and educational initiatives took place as part of Cyber Femin Club. The club worked at the intersection of artistic and social practices and was one of the first to implement participatory projects and work with various communities.” Russian Art Archive Network, https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/organization/OQFN

[59] Maria Udovydchenko, “Kurs practicheskoi nezavisimosti dlia zhenschin ‘Sdelay sama,” Russian Art Archive Network, https://russianartarchive.net/ru/research/ciberfemin

[60] P. Ageeva, “Kak v Peterburge v 90-е poiavilsia “Kiber-Femin-Klub” i chem zanimalis’ kiberfeministki,” Luna Info, https://luna-info.ru/discourse/kiberfeminizm

[61] Alexandra Shestakova, “Transformirovat’ znanie,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/78/article/1698

[62] See the Cyberfeminism Telegram сhannel – https://t.me/cyberfeminism