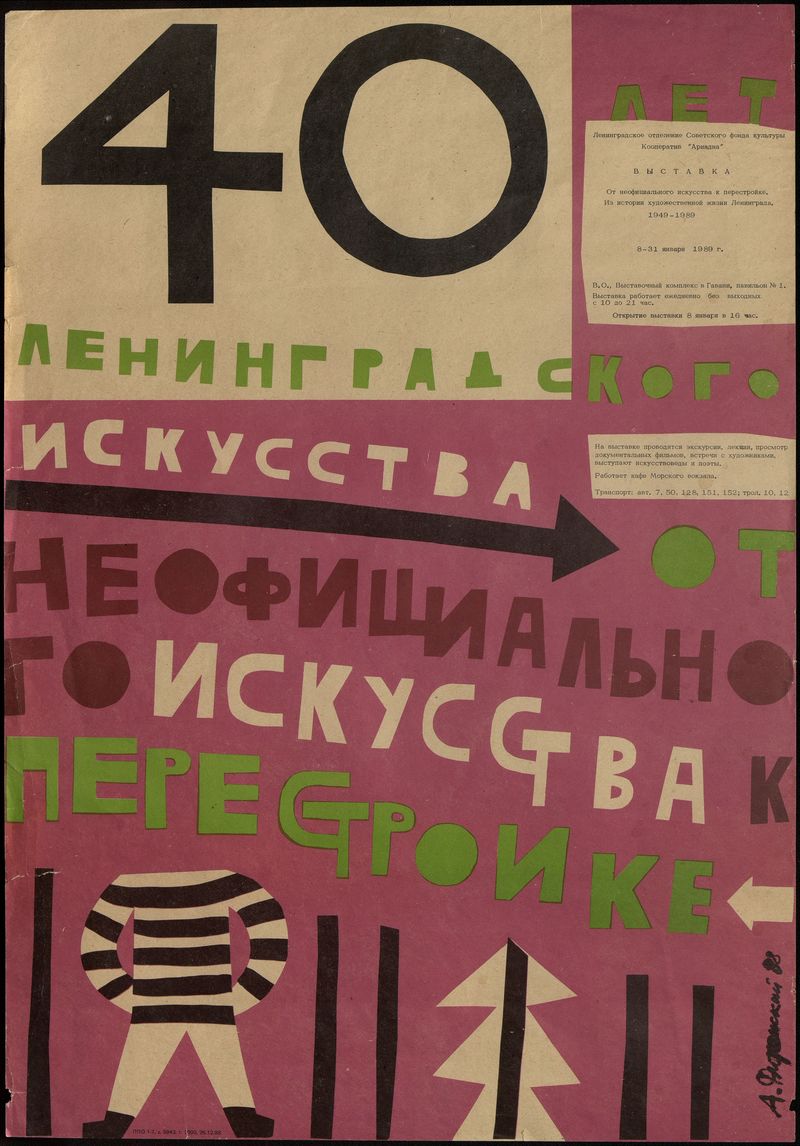

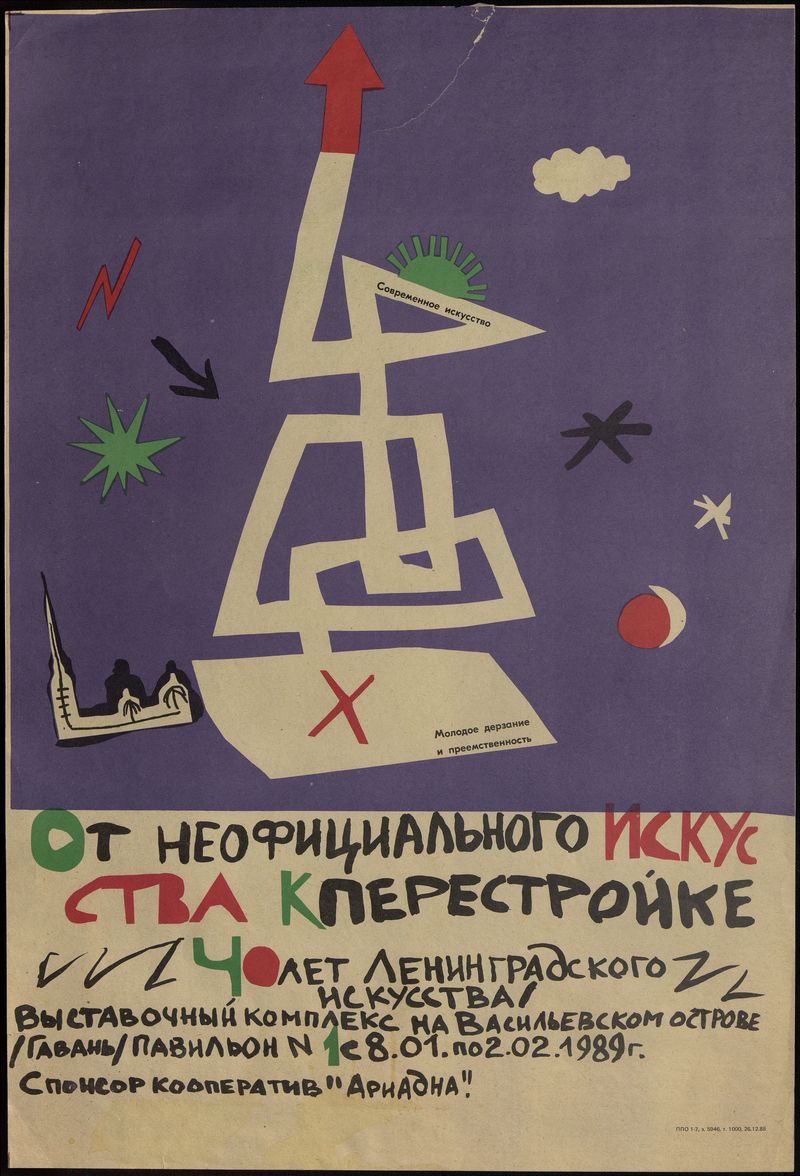

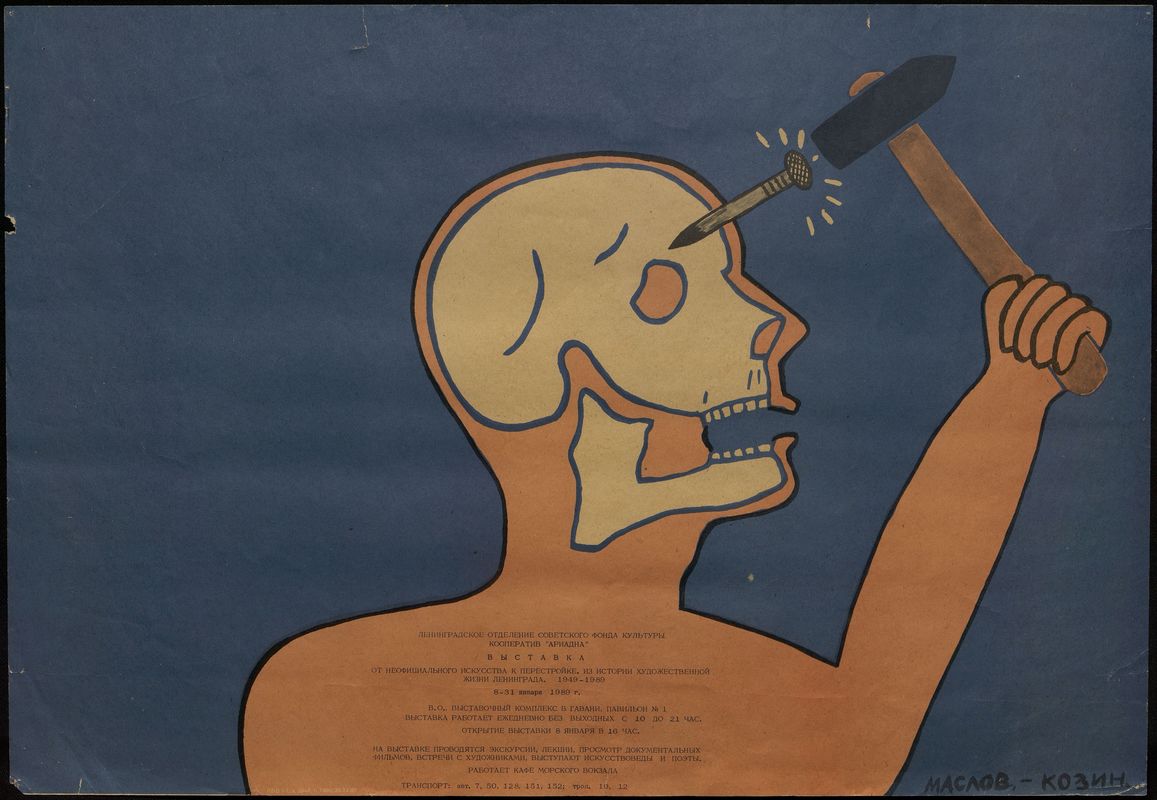

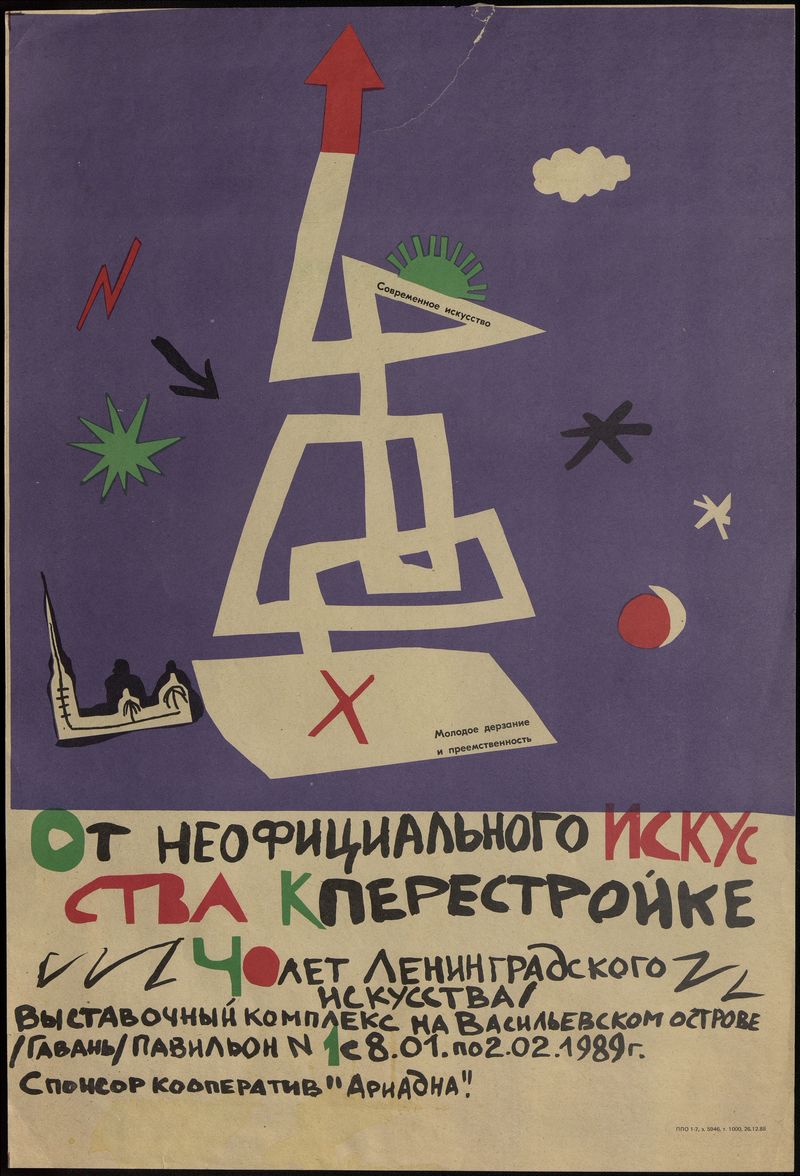

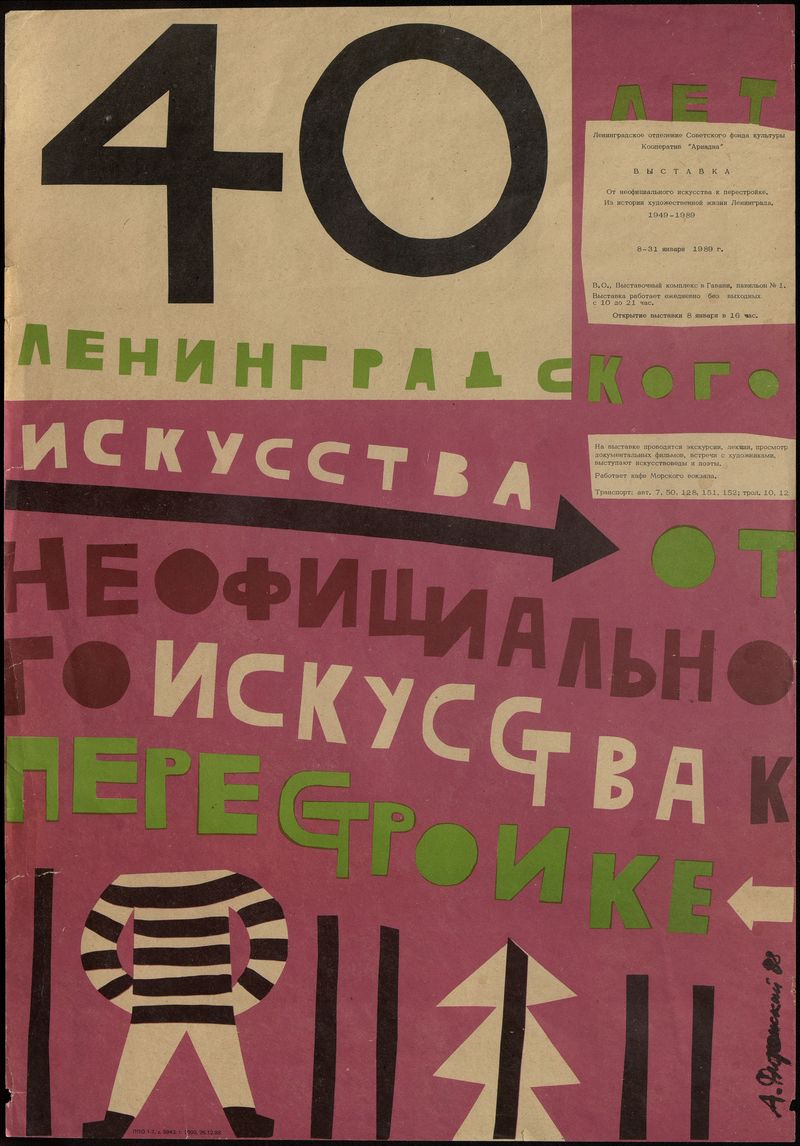

The exhibition Unofficial Art to Perestroika, which opened in Leningrad on January 8, 1989, became an event that documented the rapid changes in the local art scene brought on by the reforms in Soviet politics and economics. The history of the project was closely connected to several organizations that emerged or changed the course of their work in the late 1980s.

The first was the Leningrad Club of Art Historians, founded in 1986 as part of the USSR Culture Fund by Leningrad State University professor Ivan Chechot and several alumni. To find out more about the Club’s activities, see Alla Mitrofanova and Andrei Khlobystin’s text “Contemporary Soviet Criticism and the Leningrad Club of Art Historians” (in Russian) in Garage Archive Collection.

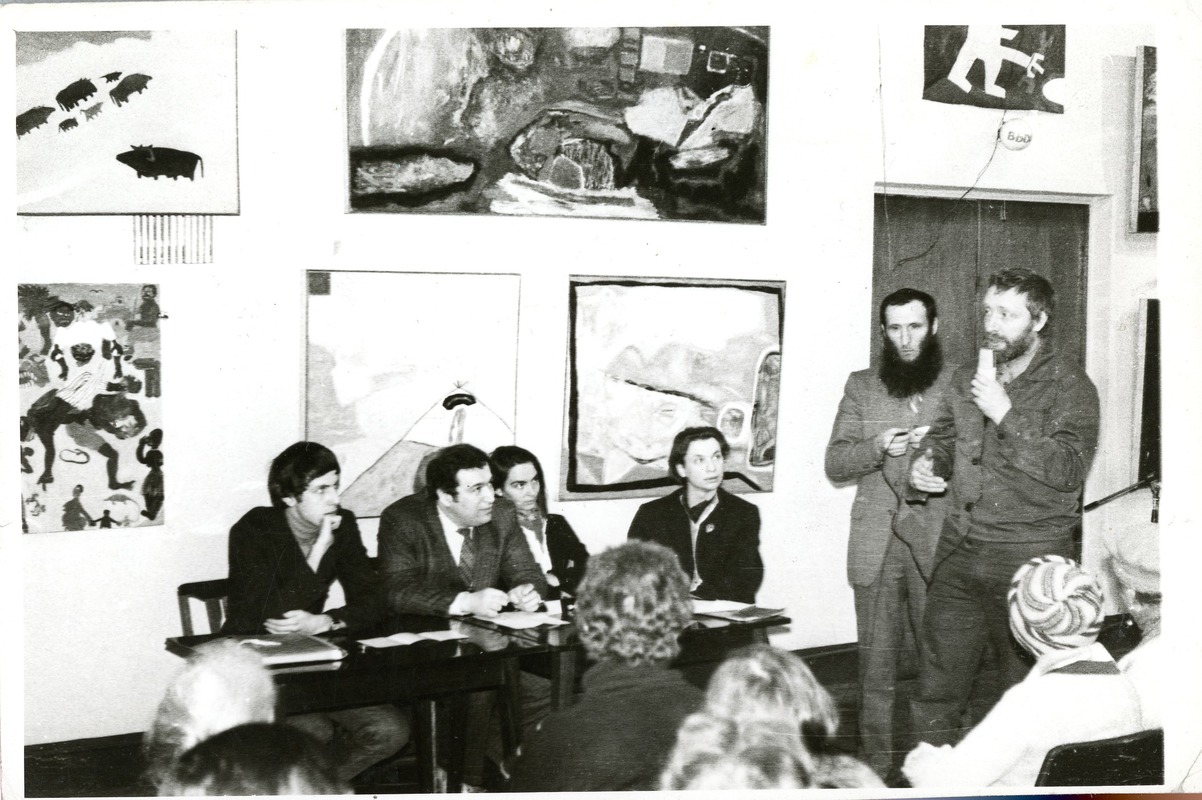

In 1987, the Club organized a conference on art and culture in the second half of the twentieth century. [1] Invited speakers included art historian Valery Turchin with a talk on the Italian Transavantgarde, author Arkady Dragomoshchenko, who spoke about postmodernism, and artist Timur Novikov, who presented his re-composition method. The future organizers of the exhibition Unofficial Art to Perestroika-Ekaterina Andreeva, Alla Mitrofanova, Olesya Turkina, and Andrei Khlobystin-who were all members of the Club, were also speakers.

Alla Mitrofanova gave a talk about the exhibition Forty Years of Modern Art, 1945-1985, which had taken place at Tate in London two years earlier. The exhibition of works from Tate’s own collection was organized chronologically and presented key artists and movements in the postwar art of Europe and the USA. [2] The idea of a museum show on very recent developments in art, as opposed to famous masterpieces of the past, must have inspired the members of the Club: From Unofficial Art to Perestroika was conceived as a similar project that would present the changing “landscape of Leningrad art over forty years,” [3] or “forty years of Leningrad art.” [4]

Another inspiration behind the project, as Ekaterina Andreeva recalls [5], was the series of exhibitions Retrospective of Moscow Artists, 1957-1987 organized by the Hermitage Association of art enthusiasts at 100, Profsoyuznaya Street in Moscow in 1987. Like their Moscow colleagues, Leningrad art historians believed that, in the local context, only art that had emerged from the underground scene or was connected to it could be considered truly contemporary.

Many members of the Leningrad Club of Art Historians worked in museums [6], however, it was the support of a private organization, the Ariadna Cooperative, that made the preparation of a large-scale exhibition on the history of Leningrad unofficial/contemporary art possible.

The economic reforms of perestroika included the Cooperative Law of 1988, which allowed non-governmental organizations to undertake commercial activities. Ariadna was among Leningrad’s first registered cooperatives that sold unofficial/contemporary art. Headed by Tatyana Kulikova, it employed Inessa Vinogradova as an art historian and consultant. She was on friendly terms with unofficial artists and also worked with Alla Mitrofanova at Pavlovsk Museum and Reserve. Initially, Ariadna did not have its own exhibition space. Perhaps, with the idea of attracting clients interested in contemporary art, the cooperative decided to organize a large-scale temporary exhibition that would feature works by artists of different generations. Alla Mitrofanova was invited to join the project through Inessa Vinogradova, followed by her colleagues from the Leningrad Club of Art Historians. This collaboration resulted in the exhibition From Unofficial Art to Perestroika at Pavilion 1 of the Harbour Exhibition Complex, which was rented for the event.

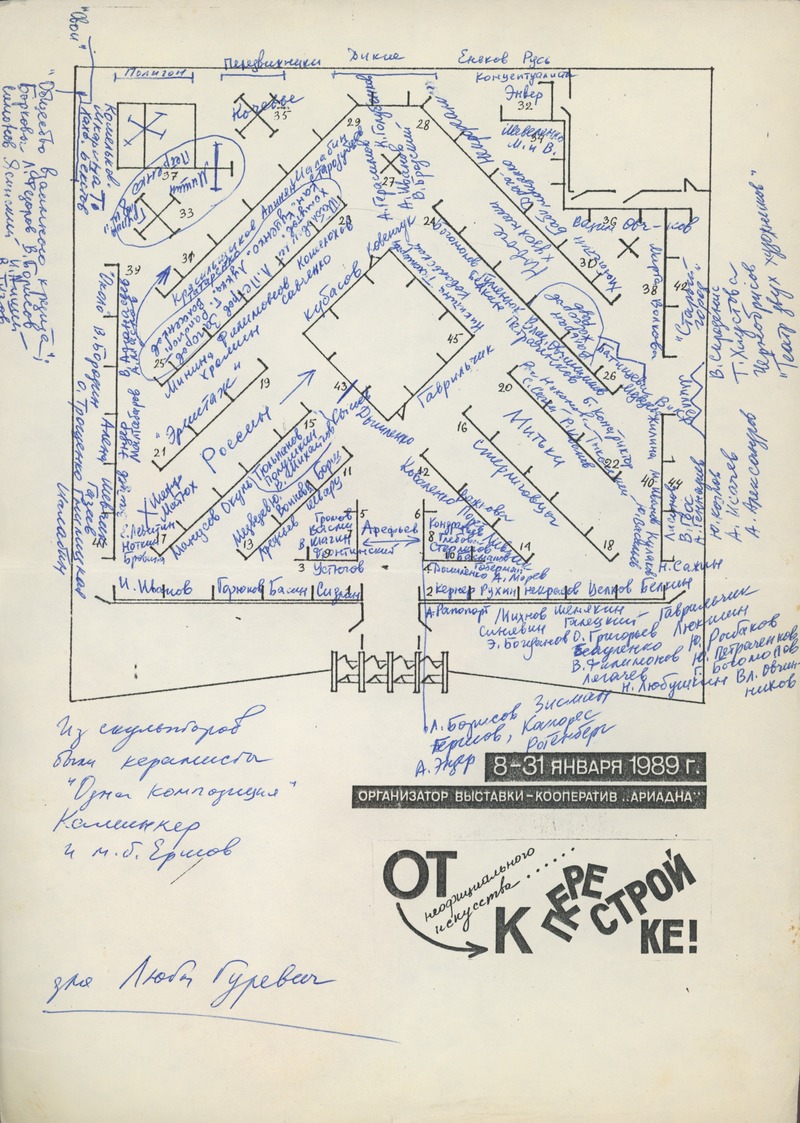

The exhibition featured “over 200 artists and around 2,000 works” [7] that presented the history of Leningrad’s “unofficial” (or nonconformist) and contemporary art from 1949 to 1989. The project, Andrei Khlobystin recalls, was co-curated by the organizers. “Alla [Mitrofanova] and I curated the New Artists, with whom I then collaborated as an art historian and an artist, the Necrorealists and the artists of the NCh/VCh squat, where I had a studio, as well as the Depressionists and other artists of the young avant-garde. Ekaterina [Andreeva] was responsible for Soviet nonconformist art, Olesya [Turkina] for the Sterligov school and Mitki group. Other curators (a role that was then unheard of) were Inessa Vinogadova and Nikolay Suvorov.” [8]

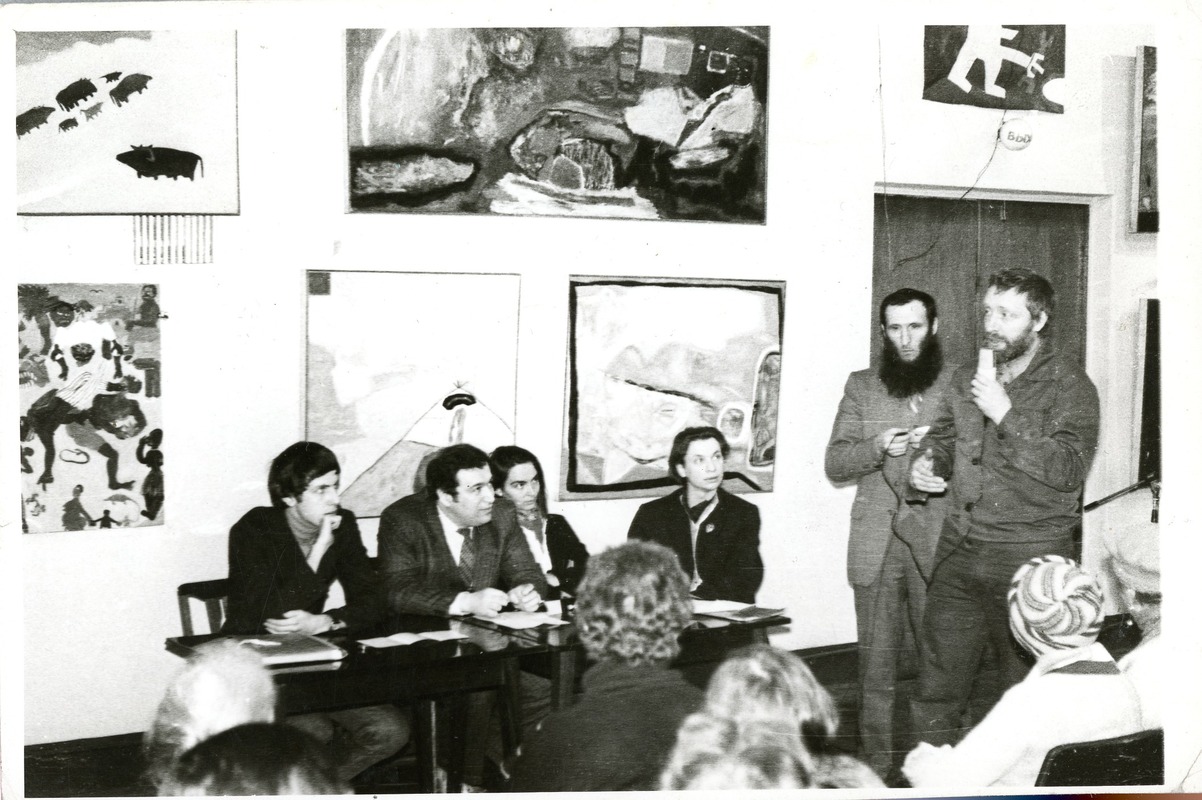

In Leningrad, official exhibitions of unofficial art spaces were quite common throughout the 1980s. Starting from 1982, the Cooperative of Experimental Art (TEII) [9] organized regular shows of “independent” artists of different generations. Their ninth exhibition, which took place at the Harbour Exhibition Complex in 1987, was one of the biggest and featured works by 160 artists, from representatives of Gazanevsky culture to the New Artists, Necrorealists and Mitki group of the 1980s. That same year the Vernisazh Association of Artists, Art Historians, and Art Enthusiasts was registered with Iosif Khrabry as its head. They also worked on bringing underground art to the broader public and organised exhibitions by Solomon Rossin, Igor Ivanov, the New Artists, Vladimir Sterligov, and others at the Sverdlov House of Culture.

The Cooperative of Experimental Art’s exhibitions were largely focused on artists who were still active on the scene. The only exhibition with a retrospective element was Contemporary Art of Leningrad at Manege Exhibition Hall. The main section of that exhibition, which opened toward the end of 1988, was focused on artists who had taken part in the Cooperative’s previous projects and the more avant-garde artists of the Leningrad Branch of the Soviet Union of Artists. Unofficial Art to Perestroika was organized in parallel with Contemporary Art of Leningrad and partly in opposition to it. The young curators believed that juxtaposing “independent” artists with members of the state-run Union was no longer interesting. Instead, they wanted to show the connections between Soviet unofficial art and the contemporary art of Leningrad. Unofficial Art to Perestroika was the first attempt to create a research-based project that reviewed the history of Leningrad’s contemporary art and the circles, schools, movements, and groups that constituted it.

In one of the explanatory texts for the project, its concept was formulated as follows:

This exhibition is essentially a follow-up to the exhibition of the art of the 1920s and 1930s at the State Russian Museum, but it has certain peculiarities that reflect the specificity of postwar art, on which is limited printed material and which has no tradition of self-reflection. Our exhibition is intended as a broad study of culture: rather than presenting a great number of artists, we wanted to outline the key movements and types of art. Our main goal was to show the scale of this era’s culture and to foster its self-awareness by introducing a number of critical, historical, and philosophical ideas regarding its development.” [10]

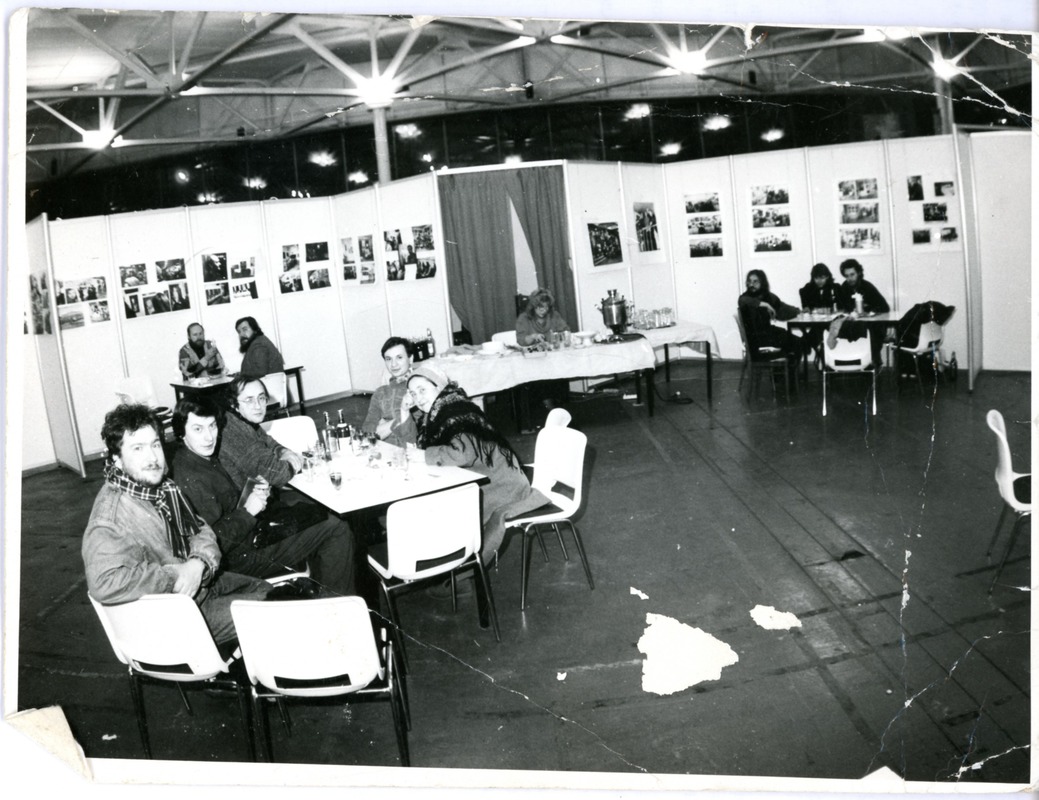

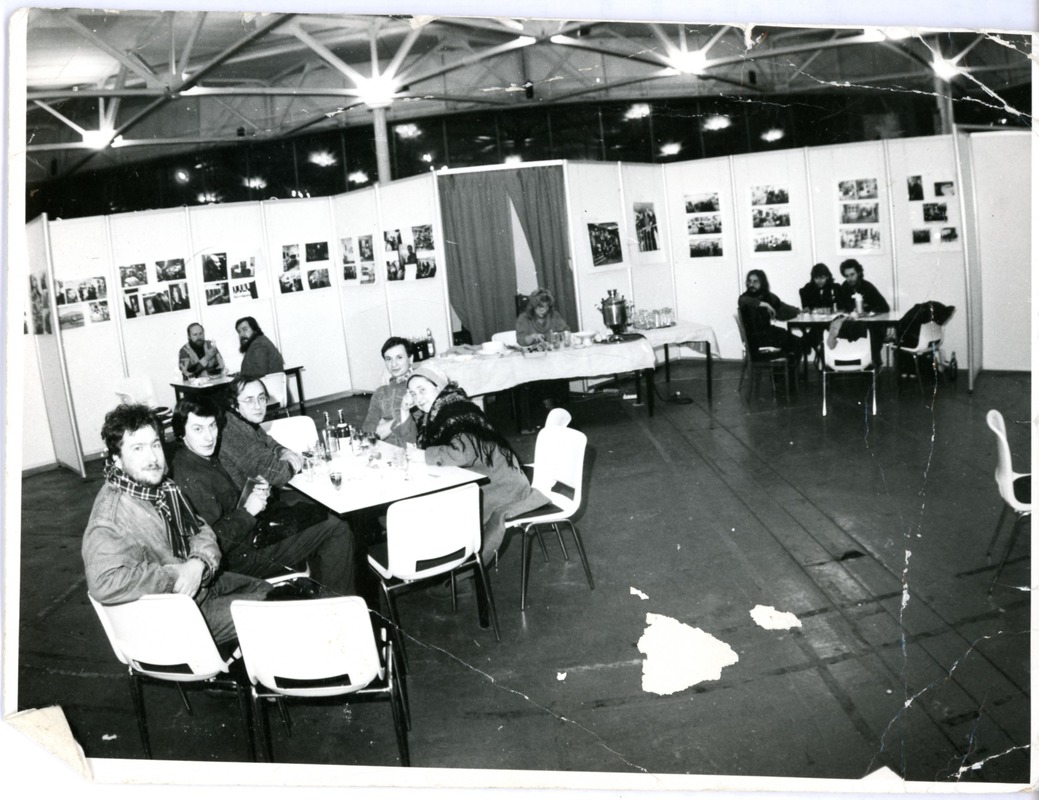

The exhibition design was based on the use of exhibition stands, which were very common in the 1980s. Corridors made of stands converged toward the central pavilion, where meetings took place and a café was organized. The exhibition opened with the artists of the Arefiev circle, the Sidlin group, the Sterligov school, the Hermitage group, and other representatives of the older generation of Leningrad unofficial art. Most artists and groups who started showing their work in the 1980s were presented deep inside the gallery space. “The exhibition was conceived as a museum of Leningrad’s contemporary art and the design was set out like a tree,” Olesya Turkina recalls. “The soil that nourished it was the apartment exhibitions of the 1970s (the symbol of Leningrad’s art life of that time) and its roots lay in the work of the students of Malevich, Filonov, and Matyushin, who continued the tradition of the avant-garde, and in the neoexpressionist movement that developed in Leningrad in the 1950s and 1960s.” [11] Garage Archive Collection holds a floor plan of the exhibition, which shows its structure.

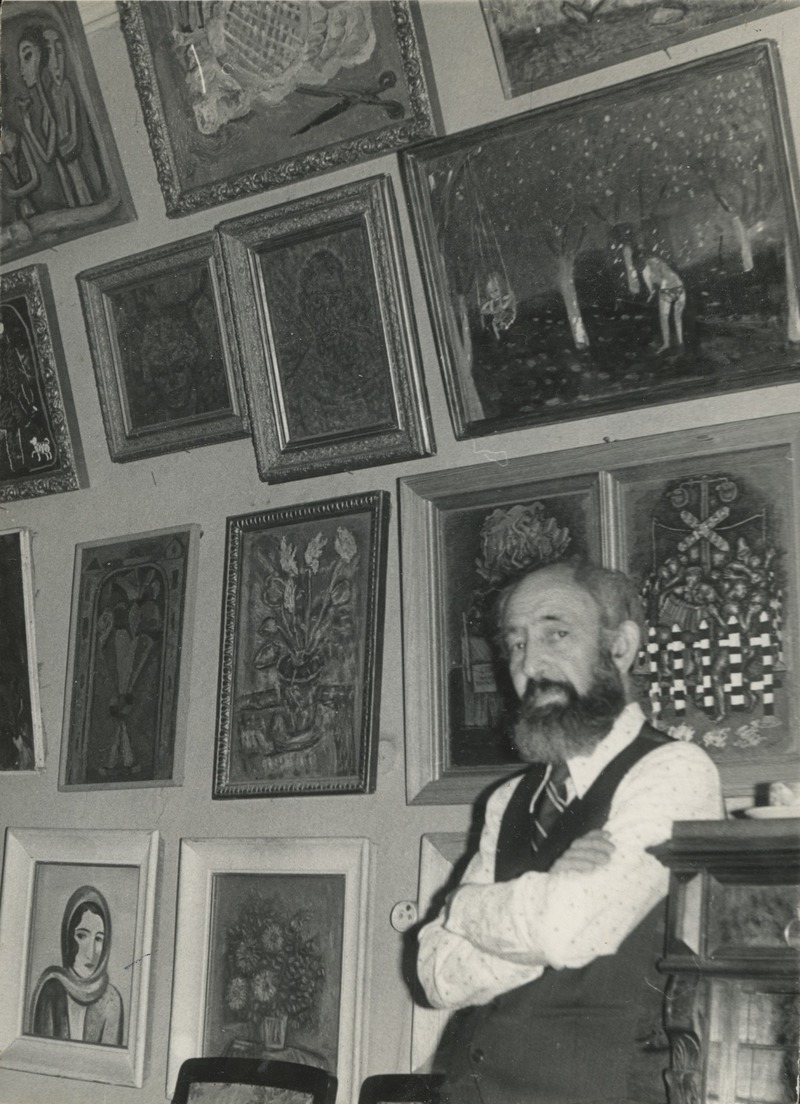

To provide a historical perspective, the exhibition also included works borrowed from collectors, as Ekaterina Andreeva explains.

“The only collector Alla Mitrofanova and Andrei Khlobystin knew was Lev Katzenelson, whose wife owned the apartment they were renting at Kirovsky Zavod. Katzenelson lived on Marat Street. He was an old man who seemed to have come out straight of the Bible. [. . .] Igor Ivanov gave me a list of phone numbers and addresses of some key collectors (Anatoly Sidorov, Irina Koreneva, Rimma Loginova, Yury Pozin, Boris Bezobrazov), a print-out of Gazanevshchina by [Anatoly] Basin, told me about [Osip] Sidlin and sent me to [Alexander] Arefiev’s friend, the architect and artist Yury Medvedev. Through Medvedev and [Dmitry] Shagin I met Oleg Frontinsky who had incredible paintings by Ustyugov and several folders with drawings by the artists of the Arefiev circle. He also had a great early self-portrait by [Richard] Vasmi…

I was just a girl who nobody knew, but the collectors were very friendly and considerate. Now I understand that they were happy to see young people finally interested in the cause to which they had devoted their lives (and some, like Rimma Loginova’s then deceased husband Igor, who was tormented by the KGB, remained devoted to it until the bitter end). Sidorov, who lived in one of the Stalin-era buildings at Sennaya Square, told me how he used to give lectures on Gazanevsky artists in his institute, and how later, when the management no longer allowed him to do that, his colleagues started inviting him home for tea to talk about paintings. That was how home lectures became a thing in the 1970s. He had hand-written business cards and a gentlemanly, encouraging manner about him. Koreneva, who lived in Tallinskaya Street, was the muse of [Yuri] Galetsky and gave me her portrait by him. She told me how in the 1970s, when she hosted apartment exhibitions, her door had to be removed so that she could not be accused of organizing them: the apartment was open, so anyone could come in and do whatever they wanted. Pozin offered my husband and me tea and cake and told us a curious story about the local policeman who came to enquire about Vladimir Ovchinnikov’s painting St. Sebastian-a composition with a prisoner in a vatnik padded jacket standing by a pylon- and whether it was a portrait of some dissident. [. . .] The oldest of the collectors, Bezobrazov, told me to come alone and came to meet me in the empty street to make sure no one came with me. They all had been through a lot and paid more than just money for their collections. I haven’t mentioned Nikolai Blagodatov yet: he had already given his collection to Sergei Kovalsky for the exhibition at Manege (there was a big rivalry between us and the Cooperative of Experimental Art at the time). But the day before the opening, Blagodatov came to the Harbour with a drawing by Basin and I gratefully included it in the exhibition.” [12]

Unofficial Art to Perestroika was first and foremost a curatorial project that presented the history of postwar art in Leningrad. However, it was also a commercial show: Ariadna Cooperative were in charge of the sales of works provided by the artists. In addition to individual buyers, the State Russian Museum acquired several works of the 1960s and 1970s for its collection. After the exhibition closed, Ariadna organized Leningrad’s first auction of unofficial/contemporary art. Participants disagree as to whether it was successful. Mixing commercial and non-commercial exhibition formats was one on the specific traits of art during perestroika, where ideas on contemporary art and ways of understanding it and working with it were formed in the local context.

Exhibition views can be found in the book TEII. Ot Leningrada k Sankt-Peterburgu. “Neofitsialnoe” iskusstvo 1981-1991 godov. [Cooperative of Experimental Art. From Leningrad to St. Petersburg, “Unofficial” Art 1981-1991]. Edited by S. Kovalsky, E. Orlov, and Y. Rybakov (St. Petersburg: OOO “Izdatelstvo DEAN,” 2007), 440-460.

1. The program of the conference is published in Andrei Khlobystin, Shizorevolyutsiya. Ocherki peterburgskoi kultury vtoroi poloviny XX veka [Schizorevolution. Notes from St. Petersburg Culture in the Second Half of the 20th Century] (St. Petersburg: Borey Art, 2017), p.116

2. For the exhibition, see Lewis Biggs, Forty Years of Modern Art 1945-1985 (London, Tate Gallery; The Burlington Magazine, 128 (998), 1986, 366-367 and 371.

3. Garage Archive Collection (Andrey Khlobystin archive), inventory number AKH.III.1989-D5476.

4. Interview with Andrei Khlobystin, April 2, 2020.

5. Ekaterina Andreeva, Materials for the biography of Timur Novikov; Timur. “Vrat tolko pravdu!” [Timur. Lie Only with Truth!], edited by Ekaterina Andreeva (St. Petersburg: Amfora, 2007), 423. One of the curators of the exhibition series Retrospective of Moscow Artists, 1957-1987, Leonid Bazhanov, also spoke about the project at the conference of the Leningrad Club of Art Historians in 1987.

6. Alla Mitrofanova worked at Pavlovsk Museum and Reserve and Ekaterina Andreeva and Olesya Turkina worked at the State Russian Museum.

7. Olesya Turkina, Iskusstvo Leningrada/Peterburga 1980-1990-kh. Perekhodnyi period, diss. kand. isk. [The Art of Leningrad/St. Petersburg in the 1980s and 1990s. The Transition Period], Candidate of Art History thesis, 17.00.04 (St. Petersburg: State Russian Museum, 1999), 74.

8. Interview with Andrei Khlobystin, April 2, 2020.

9. For more information see TEII. Ot Leningrada k Sankt-Peterburgu. “Neofitsialnoe” iskusstvo 1981-1991 godov. [Cooperative of Experimental Art. From Leningrad to St. Petersburg, “Unofficial” Art 1981-1991]. Edited by S. Kovalsky, E. Orlov, and Y. Rybakov (St. Petersburg: OOO “Izdatelstvo DEAN,” 2007).

10. Garage Archive Collection (Andrei Khlobystin archive), inventory number AKH.III.1989-D5476.

11. Olesya Turkina. Iskusstvo Leningrada/Peterburga 1980-1990-kh. Perekhodnyi period [The Art of Leningrad/St. Petersburg in the 1980s and 1990s. The Transition Period], 74.

12. Interview with Ekaterina Andreeva, April 5, 2020.