Art in the City: The History and Contemporary Practices of St. Petersburg Performance

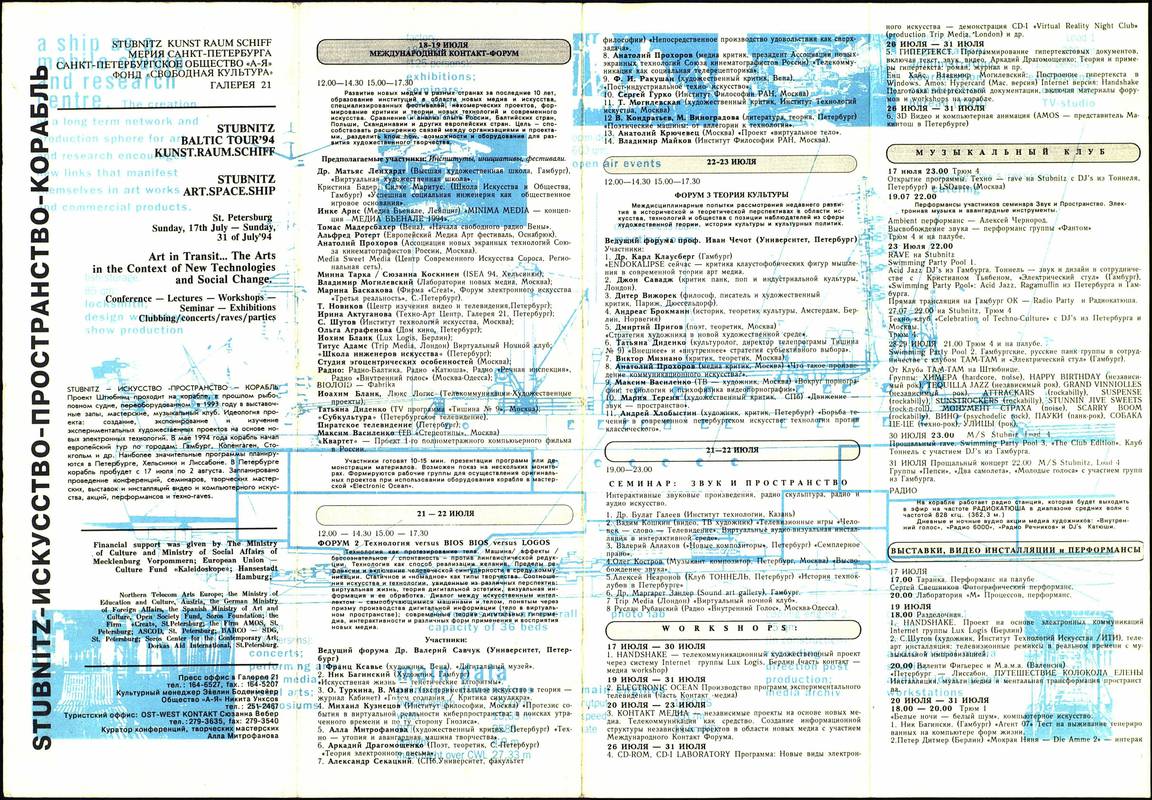

The ship Stubnitz, with European media artists on board, moored on the Neva River in summer 1994. The organizers of the Stubnitz —Art—Space—Ship project planned an intense two-week program, including an educational forum, an international workshop about new technology art, a joint exhibition by the European and Russian artists, and a series of performances, concerts, and parties. Despite of the fact that not everything went to plan, “the ship of the arts” became one of the most significant international projects to take place in St. Petersburg in early 1990s.

It all began in 1992, when the Stubnitz, an old trawler registered in the German city of Rostock, was transformed into a mobile platform by a group of artists from Austria, Germany, and Sweden. The group aimed to “create, exhibit, and study experimental art projects based on new electronic technologies.”[1] The deck and four holds of the ship were refitted to be able to run events as well offer space for exhibitions, discussions, and parties for up to 700 people. In 1993, St. Petersburg artist Victor Snesar met activists from the project and the idea of an independent cultural exchange between Germany and Russia arose. Agreements were concluded, and by May of the following year the Stubnitz left Rostock for a tour of the Baltic Sea cities. The project was curated by Austrian artist, new media researcher, and Stubnitz project co-founder Armin Medosch. The ship stopped at Hamburg, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Helsinki, but the most extensive program had been planned for St. Petersburg.

Curator and art critic Alla Mitrofanova, who worked on media art, prepared to meet the ship in St. Petersburg. Gallery 21, which had opened at Pushkinskaya, 10 a few months before the Stubnitz arrived, became a site for the project on land. The new institution fitted perfectly. Its creators, art critic Irina Aktuganova and physicist Sergey Busov, conceived Gallery 21 as the first center in the city to work with new media. The next step—the selection of artists from the Russian side—was organized through an open call. German colleagues did not participate in the selection of participants, getting involved at the last stage to include the Russian part in their existing program.

The organizers wanted to moor the ship in the historical center of St. Petersburg, but the approval procedure was delayed. The authorities were in no hurry to assist the artists, offering locations that were inconvenient or asking too high a price for mooring. With the help of official letters and long negotiations, the producer from the German side, Evelyn Bodenmeier, managed to get the necessary permission. The ship arrived in the city with a delay of ten days and moored on July 26 in front of the Mining Institute on Lieutenant Schmidt Embankment.

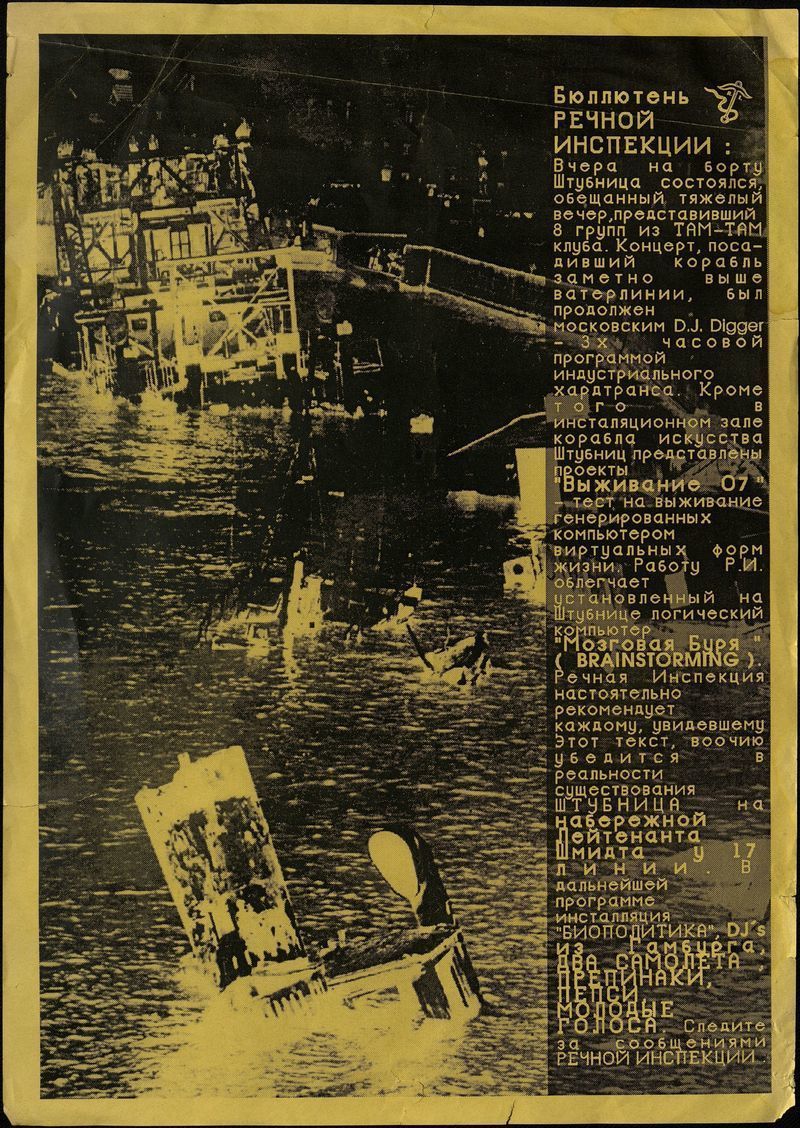

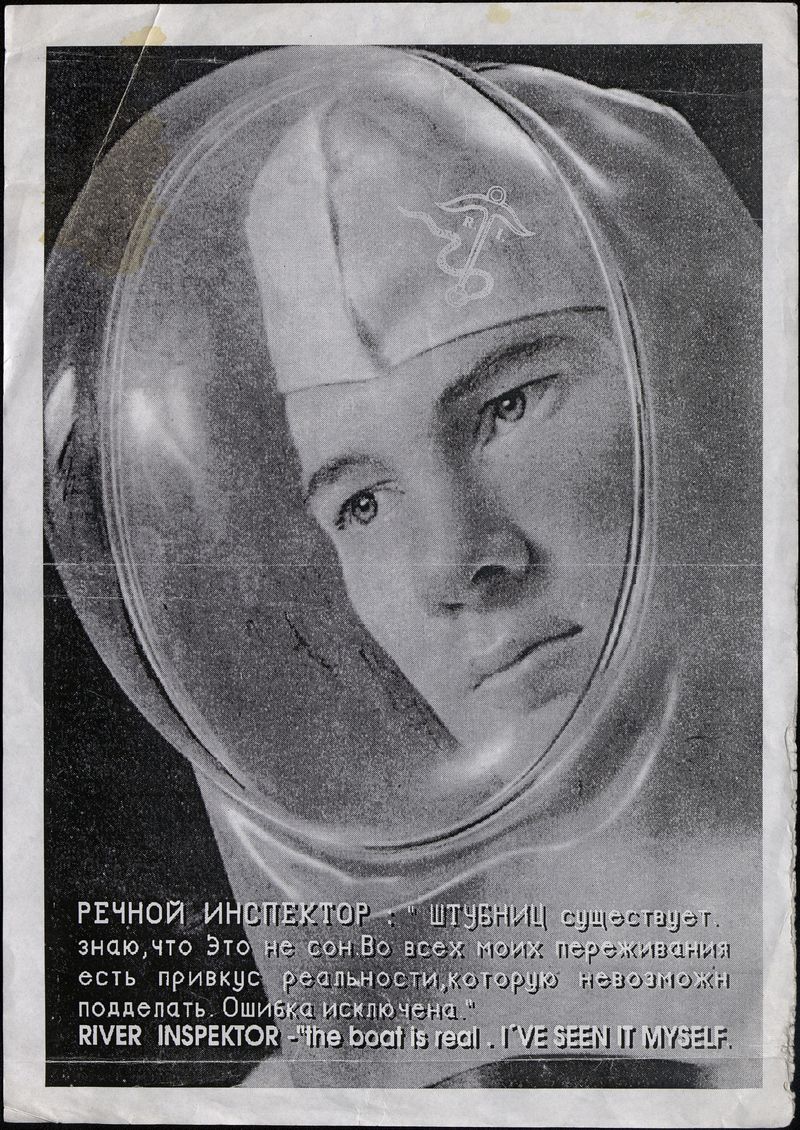

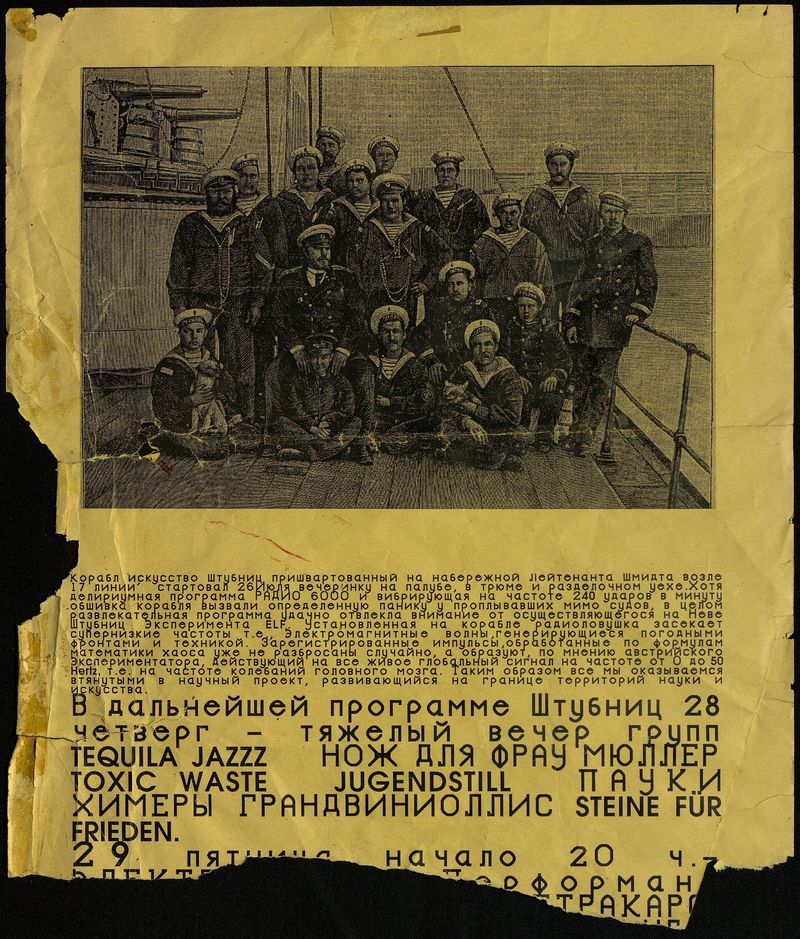

For the whole of the following week life, the Stubnitz was a hive of activity. During the day the exhibition of new media art was open and there were performances and project presentations created by European and Russian artists. The project format allowed for experiments, which led to unusual and even provocative events. Eskimo Party promised new ways of perceiving contemporary culture and took place with “fire water,” frozen cod, and “Eskimo” ice-cream, plus a fashion show by Factory of Found Clothing in which artists and poets were the models. The Candy Cocks art event, which went by the slogan “Close your eyes — open your mouth,” offered visitors the opportunity to try penis-shaped lollipops. The complete virtualization of visitors to the ship was achieved in the philosophical performance exploring “bringing up mirages,” which involved the exchange of unrealized projects ideas over a period of four hours. One the daytime program was finished, the ship turned into a nightclub offering various kinds of contemporary music. On the deck and in the holds of the Stubnitz, experimental sound performances ran in parallel with sets by techno DJs from St. Petersburg’s Tunnel and Moscow’s LSDance, as well performances by rock musicians. All this madness was recorded in the “psychoterrorist” bulletin Rechnaya inspektsiya, created by artists from Klub Rechnikov, whose publications Alla Mitrofanova called “information diversions.”

The education program took place at Gallery 21 and consisted of three forums with international participants exploring various aspects of new technologies in art. Artists, curators, historians, cultural studies specialists, media philosophers, and poets discussed the possibilities of new technologies, criticized their impact on the modern world, and made plans and forecasts for the future of digital art. There were practical lessons too: a series of workshops where European participants shared their experiences with Russian colleagues and taught them to work with digital technologies. Masterclasses were held aboard the ship, where several studios had been equipped specifically for this purpose.

The Stubnitz was in the city for less than a week, yet thousands of people visited it, despite the fact that entry was not free (some desperate people tried to take the ship by storm, jumping from the parapets or climbing the anchor chains). A parallel program was organized in the city, including parties at Tam-Tam and Tunnel and exhibitions and events at Navicula Artis and Borey galleries. A joint exhibition by Andrey Khlobystin and Eva Aephus took place at Navicula Artis, which was then located in the Nikolaev Palace, while Borey Gallery was a stronghold of opponents of new media and organized a week-long counter-program, which was not implemented.

Early in the morning of August 1, immediately after the farewell party, the ship left St. Petersburg. Its presence in the city had a significant impact on artistic life. Several events in the field of new media art took place soon afterwards: at Borey Gallery the symposium New Technologies. Pro and Contra took place; poet, Arkady Dragomoschenko created a media project for placement in the urban space; Klub Rechnikov participants continued to cooperate with the musicians and artists of the Stubnitz. Thanks to the Stubnitz, the project Cyber-Femin-Club by Alla Mitrofanova and Irina Aktuganova appeared, contributing to the development of Russian media art and feminist discourse.

[1]. Stubnitz — Art — Space — Ship program booklet (Garage Center for Contemporary Culture archive).

The project Art in the City: The History and Contemporary Practices of St. Petersburg Performance was developed by Anastasia Kotyleva and Maria Udovychenko for the podcast of the same name presented on the Museum’s booth at the 9th Cosmoscow International Contemporary Art Fair.