Art historian Sandra Frimmel explores Leonid Talochkin’s (1936–2002) collection of unofficial Soviet art, which was listed as national cultural heritage in 1976. The article is based on Frimmel’s research at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art as part of the Archive Summer program (2017) and is published here for the first time.

The Leonid Talochkin Collection of Nonconformist Art was registered as a "cultural monument of all-union significance" in 1976. In the middle of the Stagnation period under Leonid Brezhnev, the state thus accepted a double impossibility: on the one hand, the Talochkin Collection should not have existed at all, because private (art) ownership in the Soviet Union had been banned, with collections seized, and nationalized in 1918, immediately after the October Revolution; on the other hand, the unofficial art that had emerged during the Thaw had no right to exist in the eyes of the state. Yet the 1970s were also a time of negotiating and gradual opening of cultural spaces. To gain insight into this extraordinary episode in Soviet art and cultural history, the following article will focus on the question of how state recognition of the Talochkin Collection came about, in what cultural and political circumstances it took place, and what consequences it had for the collector and his holdings.

How the Talochkin Collection was registered

In 1976, the wooden house in the central Tverskoy district where Talochkin lived was due to be demolished and the collector, with all the works of art he had gathered since 1962, was to be relocated into two tiny rooms in a communal apartment on the outskirts of the city. The collection, which at that time already consisted of around 500 works, including Oskar Rabin's Optimistic Landscape, Lev Kropivnitsky's Blue Way, Youri Jarkikh's Birth–Death, and Evgeny Rukhin's The Danish Flag [1], could not have accommodated there, which put its existence in danger. To escape the threat of relocation and to request suitable premises for himself and his collection, Talochkin, on the advice of artist friends, including Dmitry Plavinsky, turned to Aleksandr Khalturin, then head of the Department of Fine Arts and Monument Protection at the Ministry of Culture. After Talochkin appeared in Khalturin's office unannounced, an almost fantastic story happened. The collector recounted it in various post-perestroika interviews: "Khalturin gets up from his chair and says: 'Leonid Prokhorovich, if I'm not mistaken?' I was amazed. I had a folder containing a letter and pictures of my collection. 'So, what do you have there?' I forgot everything I needed to say and held out the pictures. He looked at them, they were all unsigned, so he knew the artists. 'Well, well, Vasily Sitnikov, Nemukhin, Plavinsky, Weisberg! And you know, we have a proposal for you.' My eyes opened wide. 'Let's register your collection as a cultural monument. We're just about to release a law on cultural monuments protection, and it would be awesome to list your collection that way. After all, we are always being accused of persecuting artists.' Of course, I was lucky: it was time for an apology after the Bulldozer Exhibition. [...] A mere ten days later, the collection was registered. After a couple of days, they called: 'Tell Talochkin that he's been offered a two-room apartment'.”[2] It was in this apartment on Novoslobodskaya Street, very close to Talochkin's old home, that the collection was housed—or rather piled up, as it grew over the years to 1,939 items—until it was partially relocated to the Museum Center of the Russian State University for the Humanities (RGGU) in 2000.

New spaces for nonconformist art

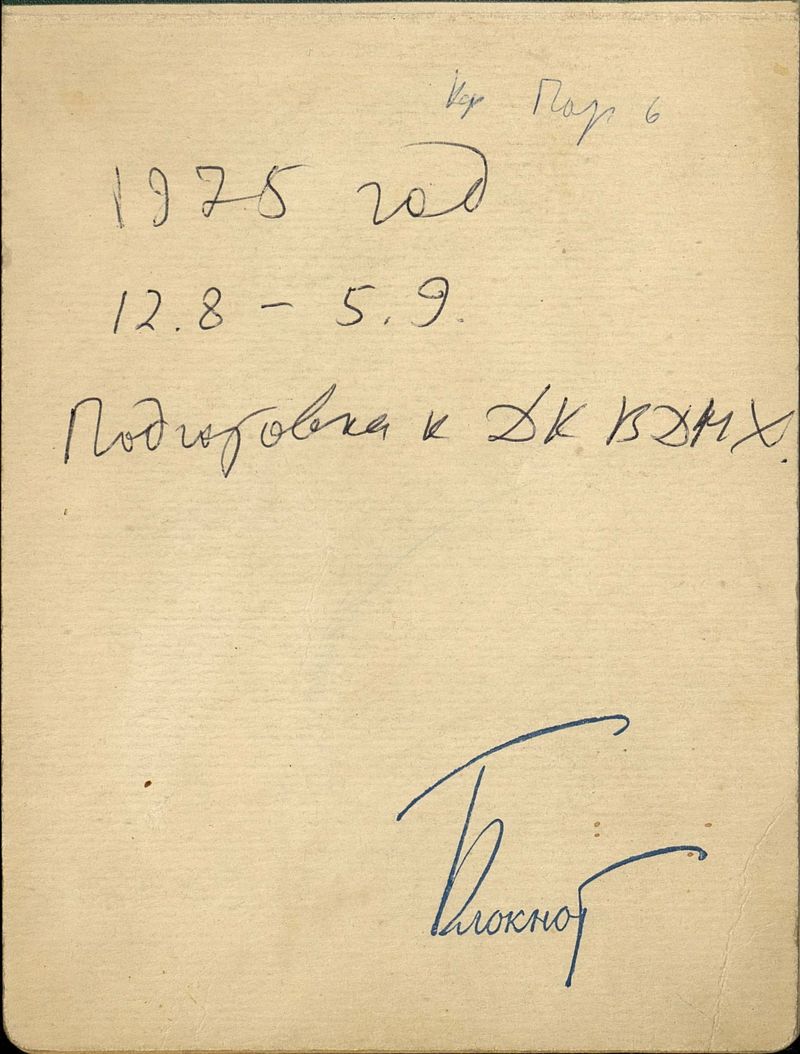

The Bulldozer Exhibition that Talochkin mentioned in his interview was an exhibition of nonconformist art organized in 1974 by Rabin and collector Alexander Glezer in an open field in Belyayevo. It was thwarted by KGB forces using water cannons and bulldozers [3]. Like the open-air exhibition in Izmailovsky Park that followed a few weeks later and the exhibition in the Beekeeping Pavilion at VDNKh in 1975, the Bulldozer Exhibition was emblematic of how artists ignored by the official art establishment sought to break out of private gatherings and apartment exhibitions into public spaces. Those efforts achieved limited success in 1976, when the Painting Section within the Moscow City Committee of Graphic Artists was founded and an associated exhibition hall on Bolshaya Gruzinskaya Street opened. The section and the hall granted the unofficial art scene public visibility for the first time since the Manège Affair of 1962—Nikita Khrushchev's angry rant at the jubilee exhibition celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the Moscow Union of Artists,[4] which had led to a division (by no means impermeable) of the art scene into official/state-sponsored and unofficial/non-state-sponsored “sides.”

Talochkin, who did not limit himself to collecting but also extensively documented the unofficial scene, photographed, archived, organized exhibitions, and also published texts in samizdat, viewed these processes with mixed feelings: "[A]part from revenge and reprisals for the defeat, the bosses started to think of how to organize and control the artists who had emerged from nowhere and had declared their existence so potently. Since the Union of Artists had shed all responsibility for them, saying that it did not want to know anything about them, the authorities turned to the City Illustrators’ and Draftsmen’s Union, which could be forced to cooperate, especially since some of the artists involved in the September battles were already members of this organization, being part-time book illustrators, and, most importantly, had a trade union roof over their heads, protecting them from charges of parasitism."[5] The state’s concession in the case of both the creation of the Painting Section and the registration of the Talochkin Collection was not simply a response to wide international disapproval accusing the Soviet Union of human rights violations as a result of its actions against the Bulldozer Exhibition. The USSR had signed the CSCE Helsinki Final Act in 1975, which stipulated, among other things, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. Accordingly, the creation of an official exhibition space for nonconformist artists, or the concomitant “officialization” of what had previously been unofficial, also enabled the state authorities to strengthen control on their part.

Collecting in the Soviet Union

According to Talochkin, Khalturin explained his almost unbelievable move by saying that after the radical action of the KGB against the Bulldozer Exhibition, the Ministry of Culture had to prove internationally "that it didn’t mind such art."[6] However, against the backdrop of the Soviet state's treatment of private collections, this explanation, which at first glance seems quite plausible, falls short. After all, hundreds of private collections—whether of fine art, icons, porcelain, etc.—had been confiscated and expropriated in 1918. But there was still a loophole. A few art collections and valuable individual objects remained in private hands, with a state-registered Protection Certificate being granted to the collectors. Such rare Protection Certificates had been issued mainly to those aristocratic-bourgeois collectors who were engaged in Soviet cultural policy and cooperated with the Bolsheviks.[7] At a time when collecting was forbidden by decree, Protection Certificates guaranteed the continued existence of the collection and prevented its confiscation by the state. They also facilitated state access to the collections, because anyone who was "registered was identified as the owner of a collection,"[8] as Waltraud Bayer writes in her comprehensive treatise on private art collectors in the Soviet Union. In this way, despite the legally precarious situation, some private collections continued to exist after the October Revolution, as long as their owners displayed good political behavior and kept silent.

However, according to Bayer, during Khrushchev’s Thaw and the early Brezhnev period, which also marks the start of the Talochkin Collection, there was a "strikingly close and diverse cooperation between the collectors’ community and the state cultural bureaucracy, which manifested itself, among other things, in museum foundations, donations, jointly organized exhibitions, in publications, and in increased museum purchases from private holdings."[9] Thus, some private collections of icons and also paintings became publicly accessible through donations, foundations, publications, and exhibitions, and some private art collections even received their own museums, e. g. the Felix Vishnevsky collection, which served as a basis for the Museum of V.A. Tropinin and Moscow artists of his time, established in 1971 in Moscow. Official cultural policy, as Bayer writes, used this turn toward excluded art primarily for the purposes of foreign policy and tourism. The liberalization of the Thaw and the attempt to consolidate foreign relations allowed and even demanded a reassessment of previously discredited art (avant-garde as well as nonconformist), which had survived only in private collections and had found its niche there.[10] That is when the state, both openly and indirectly, signaled its willingness to cooperate. The Talochkin Collection probably also benefited from this sometimes rather half-hearted reassessment, which included in the official canon art that had long been marginalized.

Talochkin also speculated that the economic problems of the Stagnation, in addition to the ostensible attempts at legalization and integration, were the catalyst for considering disfavored nonconformist art as a foreign currency earner: "Apparently, they wanted to make something useful out of our artists; to trade it to some Hammer for rusty locomotives. To achieve this, they had to promote the artists accordingly. Andropov's 1971 decree on the 'possibilities and conditions of sales of modernist artworks to foreign customers' also speaks to this."[11] This decree deals with stopping the purchase of "formalist" artworks by Western "bourgeois propaganda agencies." Andropov ordered colleagues "to explore the possibilities and conditions of sales of modernist artworks produced by some creative professionals in our country to foreign consumers. Such a measure would help to close illegal transaction channels between our citizens and foreign buyers and to establish greater control over artworks export abroad. The West’s speculations about 'persecuted artists in the USSR' would lose their footing, at least to some extent."[12] Against the backdrop of this directive, which helped shape the cultural policy of the 1970s and even led to the Soviet government's partial funding of a nonconformist art exhibition at New York's Metropolitan Museum in 1977,[13] the conciliatory attitude toward nonconformist art may have been aimed less at integrating art and its artists into society than at addressing the financial situation in the face of declining economic growth.

New control mechanisms

According to Talochkin's memoirs, the new Law on Protection and Use of Historical and Cultural Monuments that Khalturin mentioned seems to have played an equally significant role in the state's recognition of the Talochkin Collection as polishing up the image of the Soviet Union in matters of artistic freedom and obtaining foreign currency. Khalturin had been instrumental in the drafting of the law since the mid-1970s, and since 1987 he had been involved in the creation of the Unified System of Record and Storage of Historical and Cultural Monuments[14] for the entire Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries. Both the law and the database dealt explicitly with privately owned cultural monuments. In 1978, in a speech to the Ministers of Culture of the Socialist Countries, Khalturin mentioned the listing of "monuments privately owned by citizens, i.e. in private collections"[15] as an important stage in the development of the database. What had begun on an institutional level with the establishment of the Painting Section in the City Committee seems to have continued here in legislation, namely the ostensible legalization and thus also increased monitoring of the unofficial and private art and collector scene.

Collections such as Talochkin’s were legally registered under the Law on Protection and Use of Historical and Cultural Monuments of 1978 (the first version dates from 1976), which aimed to provide "the most complete identification of monuments and assistance in their preservation."16 Special attention was paid to privately owned cultural monuments. The State Control and Advisory Committee of the Department of Fine Arts and Cultural Monuments under the USSR Ministry of Culture, which specialized in the acquisition by museums of artworks held for personal use by citizens (State Advisory Committee-II),[16] was established in 1976, prior to the adoption of the new law. This commission "aimed to contribute to the replenishment of art museums’ collections with valuable works of native and foreign classics, Soviet and foreign modern and progressive fine and applied art"[17] and aimed to purchase private collections for state museums.

After registration certain obligations arose both for the collectors (Talochkin, in this case) and for the monument protection authority. Khalturin told Talochkin at the time, "You will need to let us know of any movements in your collection. If you intend to sell an artwork, we will exercise our right of first refusal. But if we can't agree on a price, you can sell it to whoever you want. If you know who you are selling it to, advise us of the buyer. If you plan to exhibit an artwork, then you also need to let us know. For our part, we can help with restoration, with the premises."[18] At first, these conditions seemed to benefit both sides. However, according to Article 29 of the Law on Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments, collections whose private owners did not comply with the rules for the “protection, use, accounting, and restoration of monuments” could be confiscated. This was especially true if the owner used the collection "for the extraction of unearned income." Such "small print" could have easily led to the nationalization of the collection under any pretext. But in the case of the Talochkin Collection, it was a paradox that the nonconformist art the state disapprove of was suddenly officially acknowledged as a cultural monument bearing artistic and cultural value. The formerly ostracized works now constituted, as it was formulated in the law, "an integral part of the world's cultural heritage"[19] and "testified to the enormous contribution of the peoples of our country to the development of world civilization," although just a few years earlier nonconformist artists had been "stopped on the street by KGB officials and threatened with court cases, physically attacked, beaten up in the course of interrogations, harassed by anonymous callers, urged to denounce their colleagues, accused of fictitious crimes, and briefly arrested,"[20] as Bayer elaborates. A similar, albeit far greater, valorization of suppressed art and its inscription in the art historical canon, in this case the avant-garde, occurred a year later in 1977 with the state acceptance of the Costakis Collection donation, which Khalturin also facilitated to a significant extent.[21]

Ultimately, at least on paper, the Law on Protection and Use of Historical and Cultural Monuments seems to have created a measured give-and-take situation between state authorities and private collectors. As Talochkin recalled: "The report they demanded was a formality. If I said that the work had gone and I didn’t know the buyer because he hadn’t given his name, that was kind of enough."[22]

Canon, control and criminalization

As a result of Andropov's order, the establishment of the State Control Committee, and the new law, the situation for private collections, especially of unofficial art, changed in the 1970s and became more advantageous. However, Leonid Talochkin's collection seems to have been one of the few collections of nonconformist art that were registered by the state in the 1970s, and it certainly benefited from this registration. Nevertheless, state support of unofficial art does not seem to have been long-lasting and probably decreased with Khalturin's appointment as director of the State Picture Gallery of the USSR and his consequent departure from the Ministry of Culture in 1979. As Talochkin recalled: "All of this was respected until the Ministry transferred such contracts to the Mossovet [Moscow City Council] Head Department of Culture. They ruined it all. Shortly after this transfer of contracts, Vera Rusanova, also a good collector, applied to the Department with a request for suitable premises (her house was also destined for demolition). The same department sent her a letter saying that her collection had no artistic value. And she has an excellent Weisberg, Nemukhin, Masterkova, Plavinsky, and many others."[23] The Rusanova and Nutovich collections of unofficial art were certainly known to the Ministry of Culture, especially Khalturin, but were not registered.

The new Soviet cultural policy by no means brought such positive effects for other collectors as it did for Talochkin. Especially in the early 1970s, some collecting disciplines had been criminalized on suspicion of "foreign exchange speculation." The 1970 trial of Boris Gribanov for trading in paintings and antiquities at inflated prices ended for the collector with a ten-year prison sentence. The Tropinin Museum, which housed Vishnevsky's collection, could not open until much later than planned because of the collector’s arrest and subsequent trial, which ended in an acquittal; and the St. Petersburg collector of nonconformist art Georgy Mikhailov was even sentenced to forced labor[25] for the "unlawful sale of photographs, slides of paintings, and speculation with works of art."[24] Although, as Bayer also writes, the strategic overtures of Soviet cultural policy to previously suppressed art movements led in some cases to the sudden promotion of "others" and their inclusion in the official canon, there was obviously a flip side: control, appropriation, even absorption—for example confiscated works never being returned, as happened with the Mikhailov collection—in order to subsequently suppress dissent.[26] Despite these still precarious circumstances, in 1976, with the registration of the Talochkin Collection as a "cultural monument of all-union significance," nonconformist art, which was just beginning to enter the consciousness of the Soviet public, was granted "artistic cultural value"[27] by law and state contract. It was thus confirmed by the state that this art "served the purpose of cultural development" and "aesthetic education."[28]

[1] Tatiana Wendelstein, Facebook post, August 22, 2017. I thank Gianna Frölicher for our discussion of this text.

[2] "Mne prosto darili kartiny. Interv’iu Nikity Alekseeva,” Inostranets, 9, March 7, 2000.

[3] See Victor Agamov-Tupitsyn, Bul’dozernaia vystavka (Moscow: Ad Marginem Press, 2014).

[4] See Yuri Gerchuk, Krovoizliianie v MOSKh, ili Khrushchev v Manezhe 1 dekabria 1962 goda (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2008).

[5] Irina Alpatova, Drugoe iskusstvo. Moskva 1956–1988 (Moscow: Galart, 2005), 202.

[6] Fedor Romer, “Dissidenty vsesoiuznogo znacheniia,” Itogi, March 7, 2000, 60.

[7] See Waltraud Bayer, Gerettete Kultur. Private Kunstsammler in der Sowjetunion 1917–1991, Vienna: Turia & Kant, 2006), 15, 58.

[8] Ibid., 59.

[9] Ibid., 185.

[10] Ibid., 185.

[11] Fedor Romer, op. cit.

[13] Bayer, op. cit., 210.

[14] A.G. Khalturin: "Protection and use of historical and cultural monuments, 6.06.1978, Suzdal (text of his speech at the meeting of Ministers of Culture of the Socialist Countries), Manuscript Department of the State Tretyakov Gallery, f. 249, storage unit 3, 12 pages., p. 6.

[15] Ibid.

[16] See: Minutes of the Advisory Committee of the Department of Fine Arts and Monument Protection, Russian State Archive of Literature and Art, f. 2329, inventory 41, storage unit 346, 11 p., p. 1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Fedor Romer: RELIQUES. THERE WAS NOT A SINGLE PENNY, AND SUDDENLY THERE IS A DIME.

[19] LAW ON PROTECTION AND USE OF MONUMENTS OF HISTORY AND CULTURE, December 15, 1978.

[20] Waltraud Bayer: The Art of Survival: Private Art Collectors in the USSR 1917-1991, Vienna 2006, 209.

[21] See: Irina Pronina: "Gift from George Costakis", in George Costakis. To the 100th Collector's Anniversary, Moscow, The State Tretyakov Gallery 2014, 384-391.

[22] Fedor Romer: RELIQUES. THERE WAS NOT A SINGLE PENNY, AND SUDDENLY THERE IS A DIME.

[23] "Other art" Leonid Talochkin. Interview with the collector. INA MAHARASHVILI. Russian Thought №4316, May 4—10 2000, 15, Garage Archive.

[24] See Bayer, 213f.

[25] See Bayer, 279.

[26] See ibid., 210.

[27] LAW ON PROTECTION AND USE OF HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL MONUMENTS, December 15 1978, Article 1.

[28] LAW ON PROTECTION AND USE OF HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL MONUMENTS, December 15 1978.