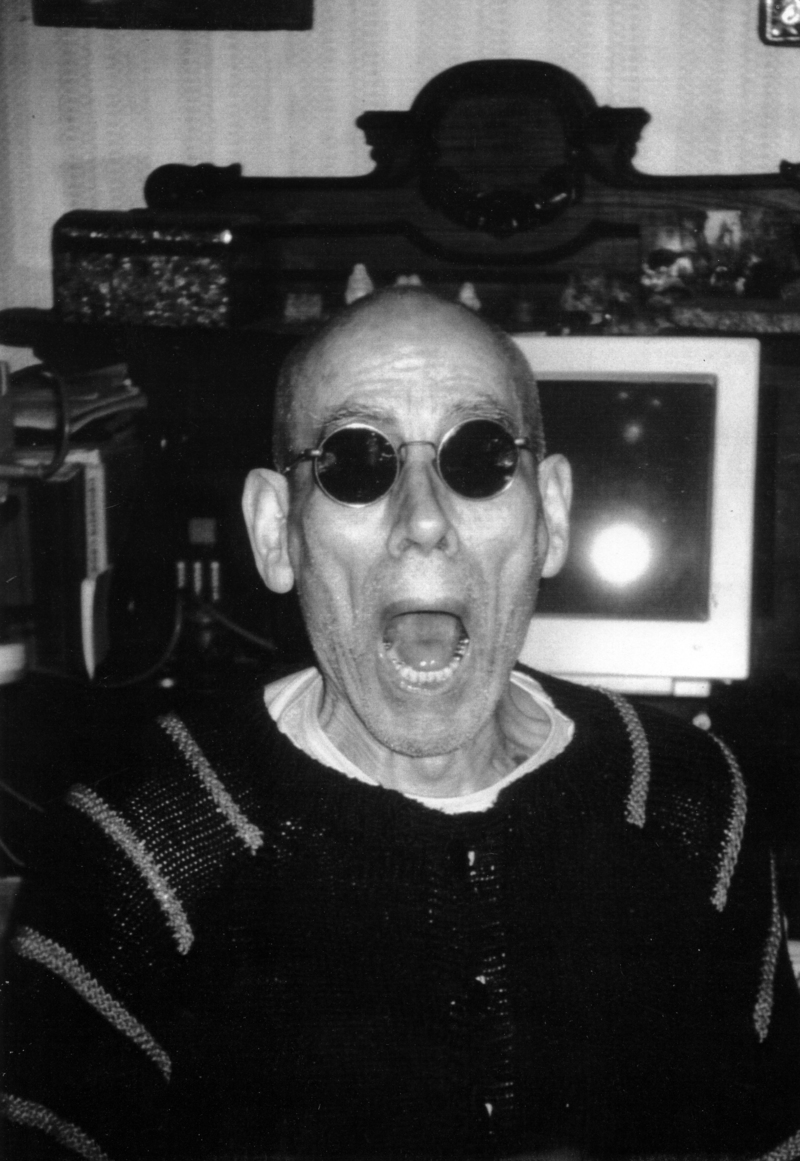

This is a transcript of a bio-inter-view with poet and novelist Igor Kholin (1920–1999), a member of the Lianozovo Group and a representative of concrete poetry in Russian literature. The interview was recorded in 1996 by Sabine Hänsgen to document the Moscow art and literary scene of the time, and is stored in her personal archive.

I had heard a lot about Igor Kholin before I met him in person in the mid-1980s.

Poet Igor Kholin was a cult figure in the Moscow conceptualist circle, to which we German Slavic scholars, who had come from West Germany on an academic exchange program, were rather close at the time. If I remember correctly, it was Andrei Monastyrski and Vladimir Sorokin who took me and Georg Witte[2] to Kholin’s apartment near Kolkhoznaya metro station,[3] in Ananievsky Lane by the Garden Ring Road. We were told that Igor Kholin was an icon of the Soviet 1960s underground, who had left the art scene and stopped writing a few years earlier and devoted himself completely to bringing up his daughter Arina after her mother died in childbirth.

Kholin immediately made a great impression on me. He was a very modern and open person: he was interested in everything that was going on in the world, including in our country, and particularly interested in fashion and new technology.

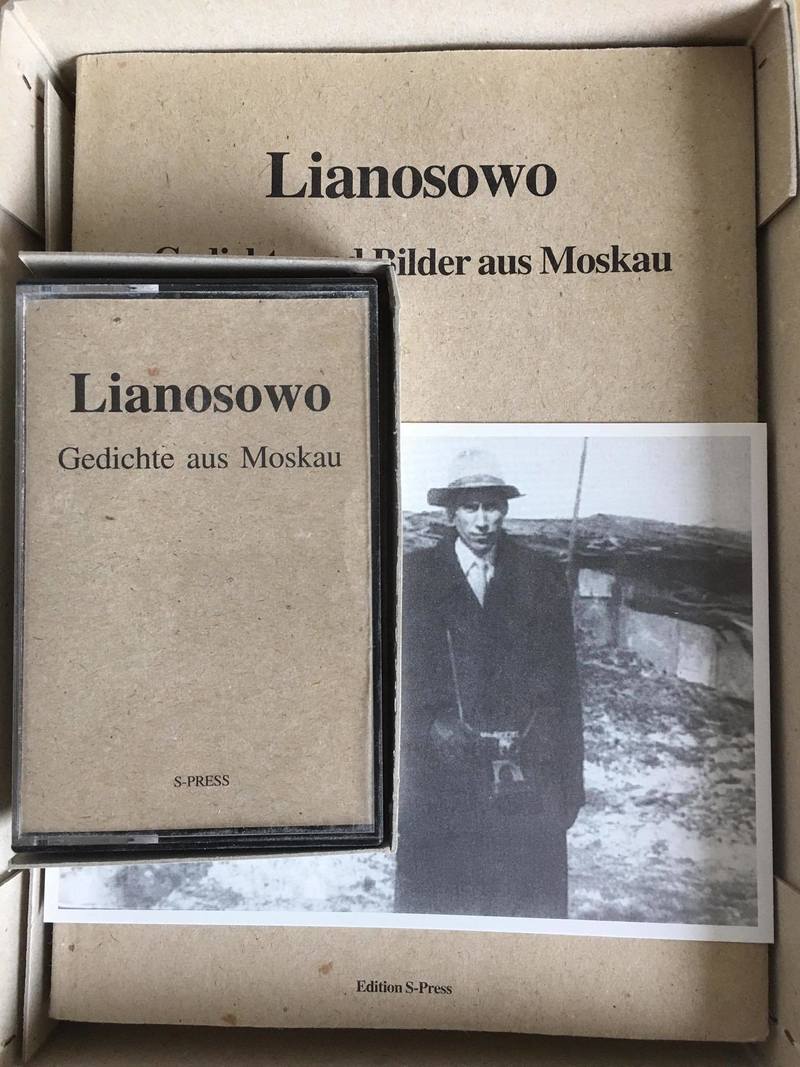

We shared this interest in technology. At the time, we were audio and video recording poetry readings, artist conversations, and performances in the Moscow conceptualist circle in order to document the specific forms of artistic communication, life in the underground—we wanted to preserve for the cultural memory what we believed might be destroyed, repressed, and forgotten. Kholin showed us his audio recordings of apartment poetry readings that he had organized in the 1960s and 1970s. Later, when in 1992 we were working on the anthology Lianosowo, Igor allowed us to include his recordings of readings by Evgeny Kropivnitsky and Yan Satunovsky in the media package that accompanied the anthology. We could not have recorded them ourselves: when we arrived in Moscow they had already passed away.

We started seeing Igor Kholin regularly. Thus began a friendship that continued until his death. Starting from the late 1980s, Kholin visited us a few times in Germany for a number of cultural events: in 1989 he came to the festival Hier und dort at Museum Folkwang (Essen)[4] and in 1992 to the exhibition Lianozowo[5] at the Bochum Art Museum (curated by Günter Hirt and Sascha Wonders[6]), followed by a tour of three Russian poets (Igor Kholin, Genrikh Sapgir, and Vsevolod Nekrasov) around Germany.[7] In 1998, Kholin came to Germany for the last time, for the exhibition Präprintium. Moscow Samizdat Books[8] at New Museum Weserburg in Bremen and the exhibition Moscow—Düsseldorf. Russian Art from Samizdat to the Market[9] at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, organized by Gudrun Lehmann[10].

In the 1990s, Kholin was very excited about the new opportunities for free travel. A couple of times he and Arina visited us in Bochum, and then traveled on to see their friends in Cologne and Paris. In fact, this might have been one of the reasons behind Kholin’s decision to transfer most of his archive to the Research Centre for East European Studies in Bremen.[11] Perhaps he wanted to give Russian researchers who gathered materials on him a reason to visit Europe like he did.

In 1996, as part of my years-long project documenting the Moscow literary and art scenes on video,[12] I offered to make a recording of Igor Kholin.

In front of the camera, Kholin spoke about his life. A host of legends circulated around him: that he had been a street child; an officer severely wounded in WWII; that he became a poet while working as a guard in a prison camp outside Moscow; that he wrote poetry about the barracks of Lianozovo.[13]

Kholin himself spread many of those legends. These stories at the intersection of truth and fantasy grew out of his conversations. Talking about his life, Kholin retold various rumors and versions of events. As he put it, it is hard to speak of something with compete certainty…

My video was screened at the exhibition Kholin and Sapgir. Manuscripts at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art[14] in 2017. That is when the interview was transcribed and translated into English.[15]

Sabine Hänsgen, 2021

Igor Kholin: I don’t really like talking about the past. First, I don’t know about everyone else, but I’ve had more bad than good things in my life. I often ask myself if there was anything good at all. So, remembering the past is always traumatic. Then, I doubt there’s a man who could tell everything about himself. I believe even Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his Confessions avoided certain painful episodes he did not want to share with the public. The story of my life is not going to be long.

It’s best to start with the day I was born.[16] I don’t remember that day of course. But I have some confused memories of my existence, so I’m going to tell you about that.

My mother was from Moscow. Well, almost from Moscow—she lived in a village near Istra. That’s where the New Jerusalem Monastery is located. People who lived there were tailors. They made coats for Moscow. In those times, one village made boots, another made coats, yet another made trousers or suits, and so on. They were really good tailors: they had actors and aristocracy among their clients. My mother was a seamstress—she made undergarments. And then, I suppose, she got married and moved to Moscow. I am her fourth child. I don’t want to bring disgrace on my mum, but all her children were from different fathers. She had been officially married to her previous husband, but not to my father. I was officially the child of her previous husband who had been shot in 1918. And as you know, I was born in 1920. Nothing is certain though, as my sisters were such liars that I couldn’t believe a word they said. Katya, for example, told me that my father’s family name was not Kholin but Lvov and that he was from around Samara—perhaps, he had some land there. I never found out. He was an officer in the tsar’s armed forces, a colonel, and then, after the Bolshevik coup, he joined the Red Army and stayed in a reserve unit in Orel. That’s where I must have been born, and then I was taken to Moscow as a baby. Why? Because my mother already had three daughters. I was adopted by some people who seemed to be merchants. They had a lot of things that pointed to that: whalebone crinoline underskirts and such. They had no children, so they adopted me. Then my foster mother must have broken up with her husband, who took to drinking, and was left alone. Besides, she finally gave birth. So, I was left at an orphanage.

The orphanage was outside Moscow, in Malakhovka. I must have had some psychological problem, because I kept running away. I ran away and they caught me. I lived on the streets, was a tramp. I was left at the orphanage in 1927, when I was seven. Where did those ideas of running away come from? I was at several orphanages. The last one was a children’s work camp in Solotcha near Ryazan. It was a former monastery, which they converted into an orphanage for minors. I had committed no crime, like most kids there, but we were considered difficult children. I was deeply impressed by that monastery. Perhaps, it was one of the reasons I started writing later. Imagine kids of 8 or 9 living in a space covered with religious murals. The image I remember the best is the one where they have beheaded John the Baptist. It was very realistic: somebody’s holding the head and his blood is dripping. There were scenes of Judgment Day too. We were looking at all that and we were scared. Then in 1932, the hunger began,[17] and children’s homes were very much affected. They stopped feeding us. It may be that some supplies did come from Ryazan but were stolen by the teachers. So, we stole food from the neighboring villages. I wonder how I survived. It was minus twenty-five or minus thirty, we had no proper clothes—some torn coats—and so we scavenged around villages. Villages were burning, there were fires everywhere.

How does this happen? When there’s war, suddenly a lot of things emerge. When there’s hunger, there are fires, villages burn. To a 10- or 12-year-old it was horrifying. Then, in 1933, a new director was appointed. I even remember his name, Lazarenko. He managed to set things right. He got some land from the local authorities—we worked there growing wheat, potatoes, turnips. They started feeding us a bit. He even bought a stallion and was taking money from the villagers for inseminating their mares. That was one entertainment we had. They’d bring a mare, and we would gather and watch.

I lived there until about 1934. Then, when I was 14, I was sent to Kryukovo, near Moscow, to work in a glass factory. I really didn’t like working there. I ran off to Crimea and lived as a tramp: sometimes I’d steal and sometimes people gave me things. In Kharkov I was picked up by a military school and joined their music group. I had learnt a bit of music in the work camp. The new director of the camp bought some instruments for us and all the kids started playing—everybody wanted to play and they didn’t take me, as I was not very musical. But after a while, other kids no longer wanted to play and I still did, so in the end they took me and I did learn certain things.

At the military school in Kharkov, we were several kids aged 14 to 16 in the music group. Then, in 1937, I started working at a power plant in Novorossiysk. First, I was learning and then became an assistant engineer. In 1940 I had to join the army. Once again, it was music that saved me. When we arrived at the regiment, the man in charge of music asked us what we could play. We were several recruits and three of us from Novorossiysk. We had been in an amateur orchestra and had even played at weddings and funerals to make extra money. So, we said we were musicians, and we were assigned to the musical troop and that’s where I served until 1941. I don’t remember which month it was, but not long before the war. There was this tension in the air. You could tell something was about to happen. We didn’t know what, of course. I really wanted to get out of there. But you can’t just leave the army—you could get shot for that. When they were recruiting people to go to a military school, I volunteered and they sent me to an army school in Gomel, and that’s where I was when the war broke out. I never finished that school. In 1941, we were sent to the front line not far from Moscow. I got my first wound near Dmitrov. I was sent to the hospital and then to a reserve division, where I did a short course to become a junior lieutenant. I became an officer. In 1942, I was badly wounded on the Don, and then after I got out of the hospital I continued fighting until the end, until 1945, until victory. Where I was, the war was still going on May 9. It was near Olomouc in Czechoslovakia. Our division stopped near Prague.[18]

After the war, I was sent to work at a local military commissariat to teach young people before they joined the army. But as it was in Western Ukraine, Bandera’s militia[19] was there. They were fighting a war similar to the one that going on now in Chechnya. They lived in the mountains and had the support of the locals. They were not “gangs,” as we called them at the time. It was quite a big organization. We had a local committee of the Communist Party, and they had their own local committee. In 1946, I was helping organize the elections and I can tell you they were totally rigged, because I, as a member of the election committee, was going around villages in an armored car with machine guns. You enter a house and of course the citizen has to vote the right way. Naturally, they did not want Soviet rule in the West of Ukraine! They killed people. Although the head of our military commissariat survived, the bullet hit his spine, so he lost his legs. When I saw that, I decided to leave the army.

I’ll tell you about one episode that you might find funny, or you might find it sad. I was preparing the papers to leave Korets in Rivne Oblast where I was serving. Suddenly an officer turns up from the forces of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. “I’d like to talk to you.” I say, “Alright.” We walk into a room, and he asks if I would like to be transferred to Internal Troops. I ask what position they would offer me, and he says, “We can offer you the post of military court secretary or military court commandant.”

Do you know what a military court commandant is? It’s an executioner. He executes people. I knew what a military court commandant was. I even wrote a short story published in the Abandoned Corner,[20] where a battalion commander is executed. And directing the execution is a military court commandant. It was a horrible execution, because they could not kill him. They must have shot him at least ten times and he was still alive. So, the commandant rushed to him with a gun to put a bullet through his head, but the gun didn’t fire. Then the guys from the commandant’s team grabbed him by the legs and dragged him into the grave—the pit they dug to bury him. You see what I have witnessed! Our polished films about heroes and all… people were slaughtered! That’s what we need to remember when we think about the war, and not heroism. Although in that war no man could prove he acted as a hero, because it was a war of masses: aviation, artillery, tanks—how could one be a hero? Nonsense. Anyway, I served until I was a captain and I quit.

Now I’m going to tell you what you’re most interested in—how I started writing. I started writing late, in 1949. I was thirty. For an insignificant administrative crime, I got two years in a labor camp. At the camp, I met a mate from the army. He was in charge of assigning jobs to prisoners. He saw my name and called for me. We could not greet each other and give each other a hug, of course, but he arranged for me to work as a prisoner-guard. They picked out some prisoners to work as guards—gave us rifles and put us on watchtowers to watch over other prisoners. We did not live in the camp, we lived outside and could walk around freely—it was not prohibited. I had to spend a lot of time on the watchtower. They really exploited prisoner-guards and sometimes you had to stay on the tower for 18 hours with no break. So, as I was standing there, I started to write poems in my mind. They were rubbish, of course. I can’t even remember anything now. Still, I became full of myself, and I thought I should learn something. I decided to go to the nearest village—Vinogradovo[21] —where they had a library. I walked in and said, “Do you have anything by Alexander Blok?” The librarian gave me a strange look (as I found out later, Blok was not to be given on loan). Then she asked me if I was writing poems. “Yes, I write poems,” I said kind of proudly. “My husband is an artist and writes poems, too,” she said, “come visit us.”

The librarian was Olga Ananyevna Potapova, the wife of Evgeny Leonidovich Kropivnitsky, who is now a well-known artist. She is also a wonderful artist. On a day off, me and a mate, who also was writing poems, went to visit them. It was not far, in Dolgoprudnoe village—we just had to cross Dmitrovskoe Highway. We were shocked. It turned out that Evgeny Kropivnitsky lived in a room of about 8 square meters with his wife, his daughter with a baby, and a granny. All in a tiny room with a wood stove. I reckon it was even worse than what we had at the camp. We talked, he asked us about our life. I read some of my poems, and my mate read some of his. Our poems were very bad, but he was a great teacher and didn’t show us that he didn’t like them. He said, “Of course, you should write, I believe it’s going to work.” So, I started visiting him, and my mate never went again. He must have thought Kropivnitsky lived too poorly for an artist. But I started visiting and became a regular there. Evgeny Leonidovich was always telling me about Genrikh Veniaminovich Sapgir, who was serving in the army at the time. He showed me his poems and sent mine to him. When Sapgir came back from the army, we already knew each other, we were friends even. Around the same time, the daughter of Evgeny Leonidovich, Valya Kropivnitskaya broke up with her engineer husband and married Oskar Rabin, a former student of Evgeny Leonidovich from the Palace of Pioneers in Leningradsky district, where Genrikh Sapgir had also studied. Oskar came to stay with them and married Valya. So, we had a small group of three poets and two artists (because Evgeny Leonidovich was a poet and an artist). That’s how it started. Later, Oskar got a room in Lianozovo,[22] as he was working there at the railroad, and our cultural hub (although we were still visiting Evgeny Leonidovich in Dolgoprodnoe) moved to Lianozovo.

I agree with Vsevolod Nekrasov, who says that the life of the circle began at Evgeny Kropivnitsky’s place and then moved to Oskar Rabin’s, even though Evgeny Kropivnitsky still played a huge part in it. We did not know what was going on in Moscow. We had our small group and that was that. Evgeny Kropivnitsky’s son Lev came back after 10 years in prison. It’s a long story. He got convicted for nothing, There was no crime, nothing. So, he came back. Then Boris Sveshnikov,[23] who did time with him, came back, and then Arkady Shteinberg,[24] who also did time with him, came back. As you see, our circle was getting bigger. Those people knew other people, so our small circle grew into a bigger cultural group. What was even more important was Evgeny Kropivnitsky’s teaching job at different Pioneer Palaces, where he taught kids art.[25] That’s where he met one of his students Yuri Vasiliev,[26] who was already an artist, a member of the Moscow Union of Artists, but a “left artist.”

We went to see his works and they were a big influence on us—on Oskar who was still making realist paintings at the time. On Lev, too. Many people will disagree now, but that’s what I think. Yuri Vasiliev knew other people: Natalya Egorshina, Nikolai Andronov. Thanks to the fact that our group was growing, we also visited some of the older artists: Alexander Tyshler, Alexander Osmerkin’s widow; the family of Artur Fonvizin showed us his works. Those visits changed our perspective on certain things. As you understand, it was all underground art: by this time Vasiliev had been expelled from the Moscow Union of Artists[27] for his experiments. However, in 1959, the first exhibition of “left artists” took place at the Central House of Literature[28] and to us it was a revelation—just like Ely Belyutin, who we met then. He ran a big studio.[29] He was an amazing, interesting person. He had up to four hundred students, and they had it going on such a scale that they could rent a steamboat and to sail down the Volga and paint landscapes. Why am I talking about Belyutin? Oh yes, it was the second exhibition of “left artists” and many artists were his students: Boris Zhutovsky and others—and Belyutin himself was a wonderful artist. Anyway, that’s what was happening then. People started having exhibitions in apartments, in studios. We met Ilya Kabakov, Vladimir Yankilevsky, Oleg Vassiliev. We had more and more connections. Finally, there came a moment where “everyone in Moscow” knew us and we knew everyone. I mean the art world, of course. In 1959, we met Ivan Bruni at an exhibition at the Central House of Literature. He was an artist and he introduced us to the newly appointed head of Malysh [a publishing house specializing in children’s literature].[30]

Genrikh Sapgir and I began writing poems for kids, for which we got paid. I wrote children’s poems[31] until 1974, and then I stopped. Life was tough, we were poor. When we got together, we’d put together our small change and buy some vodka, a couple of bottles of wine, some potatoes, and some herring. Although it was wonderful, we were very poor. Only a few amongst us were rich—either the kids of rich parents or those who got big commissions from the state, like Mikhalkov and Markov. Of course, now they are all pretending they were such good people, such democrats, but that’s not how it was. For most artists, it only got a bit better when foreigners started buying paintings. However, they were not buying our poems, so we had to look for other ways of making money. Genrikh Sapgir[32] and I wrote poems for children.

You also had other jobs. You worked as a waiter, for example.

When I came back from the camp, I got a job as a waiter at the Metropol Hotel. It paid very well—sometimes I’d get 10 or 15 rubles in tips. At a time when a qualified worker in an institute got 110 rubles a month, it was good money. I lived quite well, although I only had a room in a barrack, which I shared with my first wife and my daughter Lyuda. It wasn’t a big room, 8 or 9 meters, but compared to the room Evgeny Kropivnitsky shared with 4 people it was luxury. In 1957 or 1958 I quit that job and focused on writing. At first it was very hard, but then it got better.

Could you speak a bit about the general atmosphere of the 1960s?

I did not like the general atmosphere then. I knew a lot of dissident writers—Andrei Amalrik (the main dissident), Alexander Ginzburg, Pavel Litvinov—and I did like them, but there was something irritating about them. Now, looking back, I understand that they must have been scared. They were being watched and they could be arrested at any moment, so they were always cautious. They were not only suspicious of the authorities, but also of people they knew quite well. So, you came to see Ginzburg, and he was thinking, “Is he a snitch?” You know? That’s what the atmosphere was like. At the same time, I can say that it was a great time for art. And I don’t know if it will ever be the same again. Perhaps, only Vladimir Sorokin and Viktor Erofeev and a few other people are now working like people did then. And then it was this great moment. Art was the only thing people cared about, because they were poor.

Editing and commentary: Valeriy Ledenev

[1] The term “bio-interview” is borrowed from the futurist poet Sergei Tretyakov. However, if Tretyakov’s bio-interview (his spelling) suggested a confident view directed towards the utopian future, we in our bio-inter-view (our preferred spelling) wanted to move away from the perspective of the historical avant-garde and toward a more complex retrospective view of a twentieth-century person. At the same time, we were aware of the fact that the very situation of a conversation recorded on camera determined the mode of the speaker’s self-presentation. (Sabine Hänsgen)

[2] Georg Witte is a German Slavic scholar, literary historian, translator, and expert on Soviet unofficial art and culture. He is also known by the pseudonym Günter Hirt.

[3] Renamed Sukharevskaya in 1990.

[4] The festival of Russian and German poetry Hier und dort [Here and There] was organized as part of the Essen Days of Literature, December 8–10, 1989, at Museum Folkwang (Essen). See the exhibition booklet: https://monoskop.org/images/4/4d/Tut_i_tam_Hier_und_dort_russische_und_deutschsprachige_Poesie_1989.pdf.

[5] Lianosowo—Moskau. Bilder und Gedichte, Bochum Art Museum, June 27–July 26, 1992. The exhibition was also shown at the State Museum of Literature in Moscow (March 27–April 26, 1991) and at Sparkasse, Bremen (August 3–28, 1992).

[6] Sascha Wonders was a pseudonym of Sabine Hänsgen.

[7] “The exhibition Lianosowo—Moskau. Bilder und Gedichte and the release of the Lianozovo publication was followed by a German tour of three Lianozovo poets: Igor Kholin, Genrikh Sapgir and Vsevolod Nekrasov. The tour included readings/performances in several cities: Bochum, Cologne, Frankfurt, Bremen, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig, and Dresden. The trip to Germany made a great impression on the three poets: Nekrasov described it in his book Deutsche Buch, while Kholin donated part of his archive, including his diary manuscripts to the archive of the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen. In Bremen, the Lianozovo poets met German concrete poets Franz Mon and Gerhard Rühm.” Sabine Hänsgen, notes to the foreword, Lianosowo. Gedichte und Bilder aus Moskau (Munich: S-Press, 1992).

“In the summer we had the Lianosowo’92 program in Germany: an exhibition in Bochum and Bremen; readings in Bochum; readings in Cologne, Frankfurt (am Main), Bremen, Münster, Berlin, Dresden, and Leipzig. The three of us were reading our poetry: Kholin, Sapgir and me. With us we had Lianosowo—a new collection of poetry by us three, as well as by Kropivnitsky and Satunovsky who did not live to be there, translated by Wonders and Hirt, and an audiocassette. Over 15 reviews in 12 German periodicals and one Swiss. In Bremen, at the Bremen Museum: 3 OST + 2 WEST—a joint reading with Franz Mon and Gerhard Rühm—the living legends of German concrete poetry.” Vsevolod Nekrasov. Deutsche Buch (Moscow: Vek XX i mir, 1998), 71.

[8] The exhibition Präprintium: Moskauer Bücher aus dem Samizdat took place at the Berlin State Library (May 14–June 27, 1998) and New Museum Weserburg, Bremen (November 7, 1998–March 7, 1999). Curators: Günter Hirt and Sascha Wonders.

[9] Moskau–Düsseldorf — Russische Kunst vom Samizdat zum Markt at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf (1998).

[10] Gudrun Lehmann is an artist, art and literature historian, and translator. From 1974 to 1981 she studied art in Münster and Düsseldorf and later trained in Paris and Melbourne. From the 1980s, she visited the USSR and then Russia and the former Soviet republics several times. She has written a number of essays on the culture of Eastern and Central Europe. In 2010, her book Fallen und Verschwinden. Daniil Charms — Leben und Werk [Fallen and Disappeared. Daniil Kharms—Life and Work] was published by Arco (Wuppertal).

[11] The Research Centre for East European Studies in Bremen [Forschungsstelle Osteuropa] is a research institution at the University of Bremen founded in 1982 to study the former Eastern Bloc nations (primarily the USSR, Poland, and Czechoslovakia), their specificity and cultures. URL: www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de/ru.

[12] In 1984, I brought the Blaupunkt VHS devices from Germany to the Soviet Union and started recording events in the Moscow conceptualist scene on video. Parts of those recordings were published in Günter Hirt and Sascha Wonders, Moskau. Moskau. Videostücke (Wuppertal: Edition S Press, 1987); Günter Hirt and Sascha Wonders, Konzept — Moskau — 1985. Eine Videodokumentation in drei Teilen. Band 1: Poesie. Band 2: Aktion. Band 3: Ateliers (Wuppertal: Edition S Press, 1991).

These video pieces were featured in the exhibition Ich lebe – ich sehe https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/event/EYTW) at Museum of Fine Arts Bern (June 11–August 14, 1988) and are scheduled for reissue in 2021. Some pieces were published in the international video magazine Infermental (5, 1986; 6, 1987; 8, 1988). In the 1990s, I continued gathering the video archive as part of the MANI project (Moscow Archive of New Art). As exhibits, those videos were first featured in my exhibition MANI Museum Video Archive at Obscuri Viri in Moscow (March 30–April 4, 1996) https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/document/E10237. In the decades that followed I continued to make videos as part Collective Actions’ practice. I also documented the trips of Russian artists to the West, including the series Lecture Performances by Moscow conceptualist poets and artists at Lotman Institute of Slavic Studies and Russian Culture, Ruhr University Bochum.

See: “Moskovskii kontseptualizm 80-kh: interv’iu s Sabinoi Khensgen (Tsiurikh),” Gefter.ru, 17.10.2016, http://gefter.ru/archive/19732; Antonio Geusa, “Videotvorchestvo i khudozhestvennoe soobshchestvo. Istoricheskie paralleli mezhdu SShA I Rossiei,” Moscow Art Magazine, http://moscowartmagazine.com/issue/30/article/564.

[13] Until the early 1960s, Lianozovo was a barrack settlement outside Moscow, and in the 1960s it became a village of Moscow. In the early 1950s a circle of poets and artists formed in Lianozovo, who organized apartment exhibitions and poetry readings. This circle came to be known as the Lianozovo Group and its members included Evgeny, Lev, and Valentina Kropivnitsky, Olga Potapova, Igor Kholin, Yan Satunovsky, Genrikh Sapgir, Vsevolod Nekrasov, Nikolai Vechtomov, Oskar Rabin, and Vladimir Nemukhin, among others.

[14] The exhibition took place at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art from May 20 to August 17, 2017 and was curated by Sasha Obukhova and Ekaterina Lazareva.

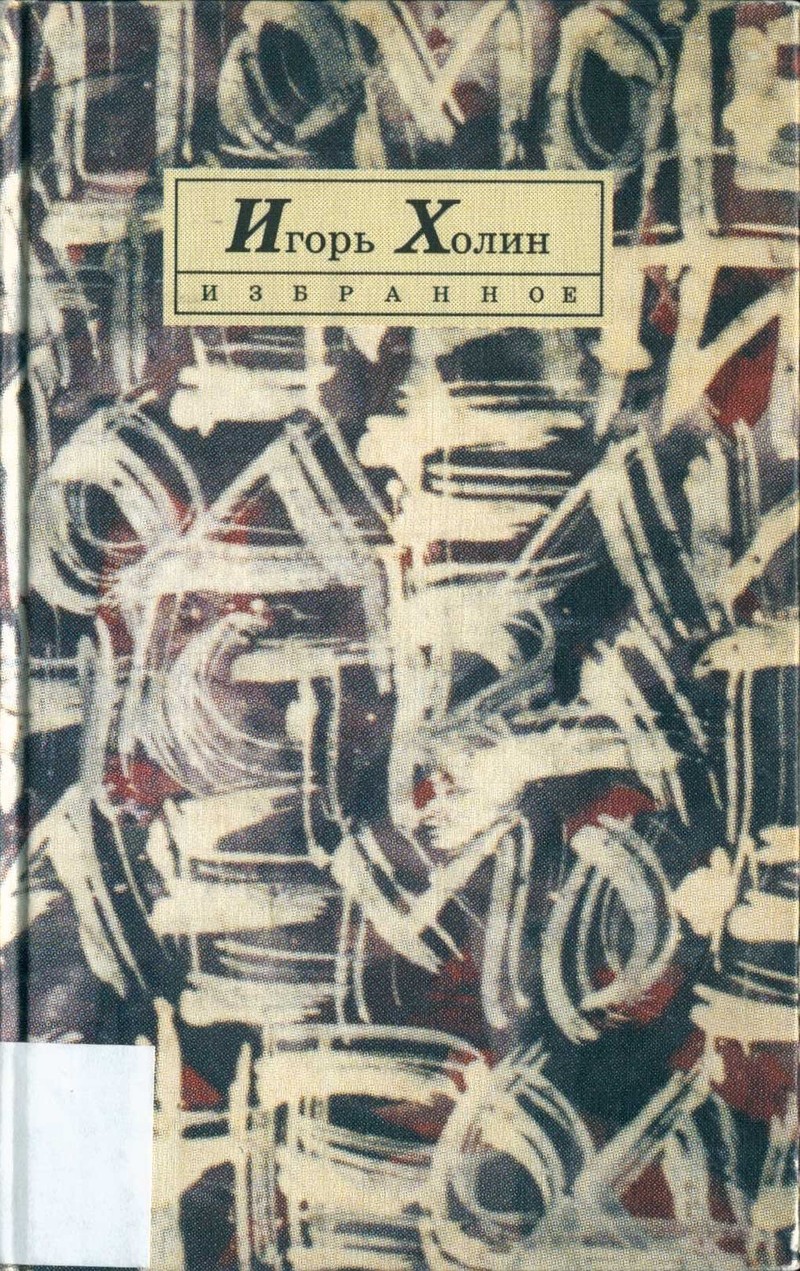

[15] For the centenary of Igor Kholin’s birth in 2020, the small German publishing house Aspei (Bochum) produced a three-part German publication of his works, which included this bio-inter-view. See: CHOLIN 100. Eine Werkauswahl in 3 Teilen ((1) Es starb der Erdball. Gedichte, Übertragung: Gudrun Lehmann; (2) Ein glücklicher Zufall. Prosa, Übertragung: Wolfram Eggeling; (3) Bio-Inter-View, Videoaufzeichnung und Transkription: Sabine Hänsgen) (Bochum: Edition Aspei, 2020). Graphic design by Martin Hüttel.

[16] January 11, 1920.

[17] The Soviet famine of 1932–1933 spread across vast territories in the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic, Central Black Earth Economic Region, the North Caucasus, the Volga Region, the Urals, and Western Siberia during mass collectivization. See: Famine in the USSR. 1929–1934. Volume. 1: 1929—1932, http://alexanderyakovlev.org/fond/issues/1015374.

[18] The Moravia–Ostrava offensive was an operation by the Red Army against the German forces in Czech Silesia (where the city of Olomouc is located). From May 6 to 11, 1945, Soviet forces continued the Prague offensive—the Red Army’s last strategic operation in World War II.

[19] The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B) was headed by Stepan Bandera from 1940 to 1959. After WWII, the organization continued as a guerilla movement in Western Ukraine (some OUN members lived in emigration outside the Soviet Union). The last traces of the movement in the Soviet Union were destroyed in the 1950s. See: Serhii Plokhy, Chelovek, snreliavshii iadom (Moscow: AST, 2019).

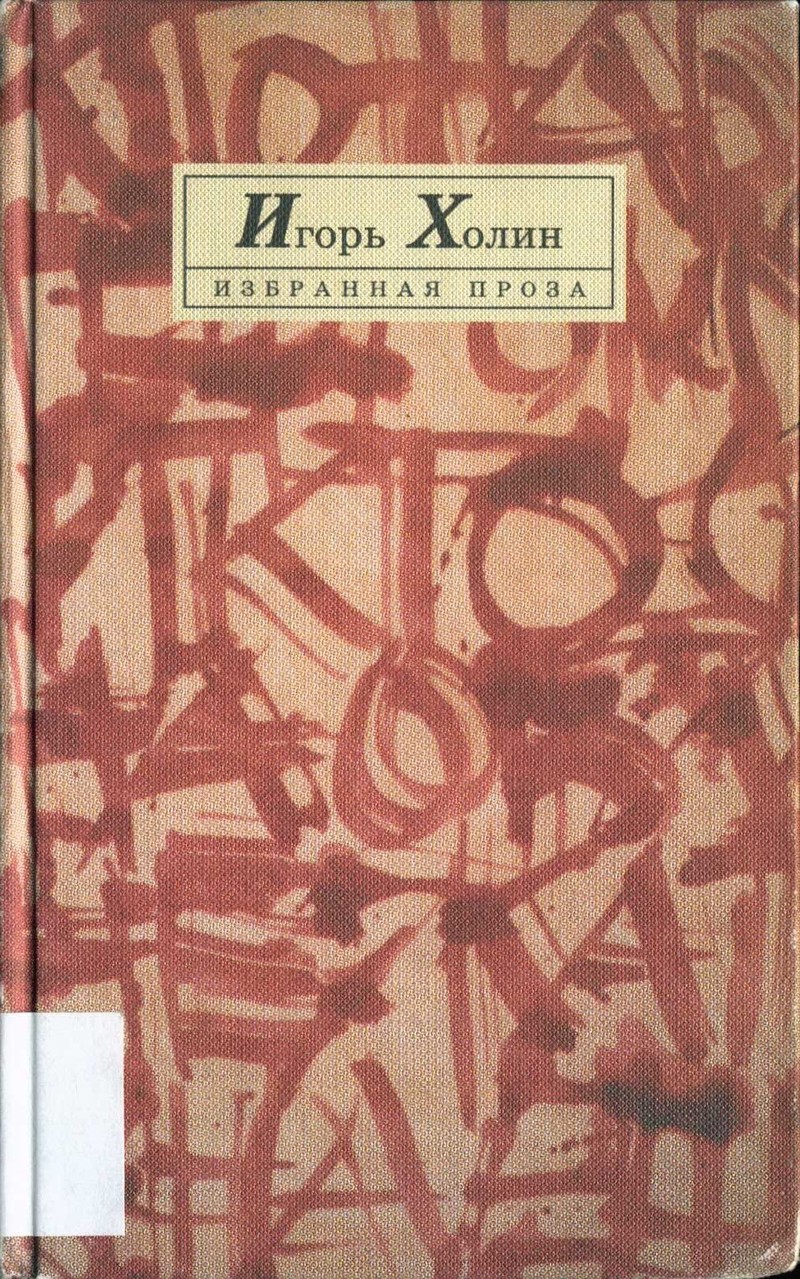

[20] Igor Kholin, “Zabroshennyi ugol” in Izbrannoe (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2000), 86–88.

[21] The village is located north of Moscow, near the town of Dolgoprudny and Lianozovo, see footnote 13.

[22] From 1950, Oskar Rabin worked as a foreman unloading trains at the construction site of the northern waterworks near Lianozovo station on the Savyolovskaya railroad line. As a worker, he was provided with accommodation near the construction site in a former prison camp barrack. See: A.D. Epstein, Khudozhnik Oskar Rabin: zapechatlennaia sud’ba (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2015).

[23] Artist Lev Kropivnitsky was sentenced to 10 years in a prison camp in 1946 and released in 1954, without the right of return to Moscow, so he remained in Kazakhstan. He was fully rehabilitated in 1956. He spent his first year in prison with artist Boris Sveshnikov, who was arrested the same year. See: A.D. Epstein, Khudozhnik Oskar Rabin: zapechatlennaia sud’ba (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2015).

[24] Artist, poet and translator Arkady Shteinberg (1907–1984) was arrested twice—in 1937 and 1944—and spent around 11 years in prison. After his release in 1954 he settled in Tarusa, where his circle included Konstantin Paustovsky, Boris Sveshnikov, and Nadezhda Mandelshtam. See P. Nerler, “Nashe glavnoe tvorenie—my sami…,” http://lechaim.ru/academy/arkadii-shtejnberg.

[25] In the 1940s, Evgeny Kropivnitsky ran an art studio in the Pioneer Palace in the Leningradsky district of Moscow, where Oskar Rabin and Genrikh Sapgir met during the war. See. Sabine Hänsgen, “Lianozovo: Periphery Aesthetics,” https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/146710/1/Lianozovo_Belgrad_p195-206_Haensgen.pdf.

[26] Yuri Vasiliev-MON (1925–1990) was a Soviet artist and sculptor. He studied at the Moscow Institute of Applied and Decorative Art (1948–1952) and the Surikov Art Institute (1948–1952) under Vasily Yefanov. He was an unofficial student of Evgeny Kropivnitsy. See: https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/person/PBKZQ.

[27] According to the publication Yuri Vasiliev-MON (1993), Vasiliev was accepted into the Moscow Union of Artists in 1954, but the catalogue for the exhibition Other Art. Moscow 1956–1976 (1990) suggests a different date—1955. After his acceptance he took part in a number of Union exhibitions, including 30 Years of the Moscow Union of Artists in 1962 at the Moscow Manege. There is no mention of his expulsion from the Union in any sources studied.

[28] Kholin must be referring to the exhibition of the artists of the City Committee of Book, Graphic, and Poster Artists that took place at the Central House of Art Workers in 1959, and in which Ely Belyutin’s studio took part. Artists included Aleksandr Sysoev, Ülo Sooster, Leonid Lamm, and Vera Preobrazhenskaya, among others.

[29] Ely Belyutin (1925–2012) began teaching in 1953, when he became a Candidate of Arts and an invited lecturer at the Professional Development Studio of the Institute of Print. The first exhibition of Belyutin studio’s artists took place in November 1959 at the House of Textile Industry Models in Moscow. In 1959, Belyutin was accused of “formalism in art” and dismissed from the Institute. In 1958, his students started training outdoors and from May 22 to June 6, 1961, the studio went on their first “sailing art course” on board the rented river boat Dobrolyubov, which sailed from Moscow to Gorky [now Nizhny Novgorod] and back. See Drugoe iskusstvo, Moskva: 1956–1988 (Moscow: Galart, 2005); Studiia “Novaia real’nost’” (1958–1991). Transformatsiia soznaniia (Moscow: Maier, 201.

[30] In 1954 Yury Timofeev was appointed head.

[31] Igor Kholin’s published children’s books include: Zhivye igrushki (Moscow: Detsky mir, 1961), Zhadnyi liagushonok (Moscow: Detsky mir, 1962), Eto vse avtomobili (Moscow: Malysh, 1965), Kto ne spit? (Moscow: Malysh, 1966), V gorode zelenom (Moscow: Malysh, 1966), Chudesnyi teremok (Moscow: Malysh, 1971), Vertolet (Moscow: Malysh, 1972), Vstalo solntse na rassvete (Moscow: Malysh, 1974), and Podarki slonenku (Moscow: Malysh, 1978).

[32] Children’s books by Genrikh Sapgir published during his lifetime include: Skazka zveznoi karty (illustrated by Alisa Poret, Moscow: Detsky mir, 1963), Zvezdnaia karusel’ (Moscow: Detskaya literatura, 1964), Zveriatki na zariadke (Moscow: Fizkultura I sport, 1970), Chetyre konverta (Moscow: Detskaya literatura, 1976), and Liudoed i printsessa (Moscow: Podium, Vse zvezdy, 1991). Genrikh Sapgir’s children’s books continued to be published posthumously. See: https://garagemca.org/ru/catalogue?authors=3fd2b9c6-184c-4f0b-a242-ff8dbb46cc97.