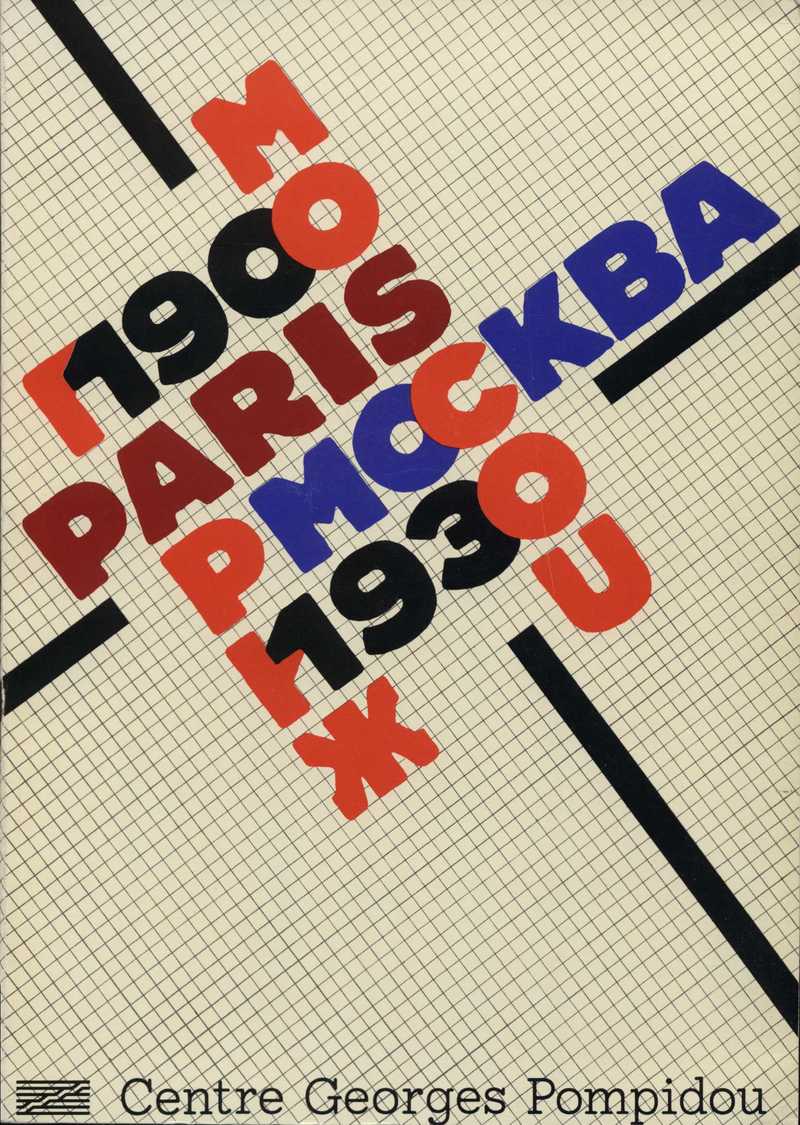

The exhibition Paris – Moscow 1900–1930 took place at the Centre Georges Pompidou, in Paris from May 31 to November 5, 1979. Moscow – Paris 1900–1930, which was conceived as mirroring the Paris exhibition, was shown at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts from June 3 to October 4, 1981. The two exhibitions constituted a major discovery for Western and Soviet audiences. Works by the Russian and Soviet avant-garde in the exhibitions were almost completely unknown visitors on both sides of the Iron Curtain before that moment. This was the first time such a large number of works by Western modernists has been shown in Moscow.

Pontus Hulten was a chief commissioner of the exhibition on the French side, while Jean-Hubert Martin was a curator of painting and sculpture section. During his visit to Moscow in September 2019 he talked to curator Andrey Erofeev on details of organising both of the shows and answered questions of Garage Archive curator Sasha Obukhova on the 3rd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, that he curated in 2009, and the new generation of Russian artists.

Andrei Erofeev: If I am not mistaken, the idea for the exhibition came from Pontus Hulten, [1] and it was initially planned for three cities instead of two.

Jean Hubert-Martin: That is absolutely right. The program proposed by Hulten for the opening of the Centre Pompidou in 1977 initially included two large group shows: one tracing the axis “Paris – New-York” and the other one “Paris – Moscow – Berlin” (in this order). He planned to show how, when artists emigrated from one country to another, the French avant-garde found its way in Moscow and then traveled to Berlin. Out of that came the idea for three solo exhibitions by Duchamp, Picabia, and Malevich, all as part of the same opening.

The exhibition Paris – Moscow – Berlin exhibition was planned for the opening in 1978, so in 1976 Hulten travelled to the USSR to meet the Minister of Culture. The feedback he received was positive. The Soviet side was ready to start negotiations. Hulten came back to Paris in high spirits: we were getting Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso from the Shchukin collection! He was happy that he wasn’t simply shown the door, but deep down he realized that it was too soon to celebrate. From the 1950s, artworks from the Shchukin collection had been lent as part of the cultural exchange program between France and the USSR. What we really wanted to see was the Russian avant-garde, of which we knew nothing back then. In 1977 I joined Hulten on a trip to Moscow. The spirit was still very positive: the Soviet side wanted to make an exhibition together, however 1978 was too soon for them and they asked for it to be a year later and without Berlin.

The exhibition was postponed to 1979 and was renamed Paris – Moscow, so we had to fill the gap in 1978 with something else. Pontus thought to bring the Costakis collection to Paris, [2] while I, young and enthusiastic, suggested organizing the exhibition Paris – Berlin. We had very little time, but decided to do it. We contacted Werner Spies, [3] and he was put in charge of the German part, while I worked on the French.

AE: Who was included in the team of specialists working on the three-part exhibition, the way it was conceived in 1976?

JHM: Pontus Hulten was chief commissioner on the French side. I was in charge of painting and sculpture. Our team also included Raymond Guidot, [4] who was commissioner for applied arts, graphic design, architecture, and urban planning, and Serge Fauchereau [5] working as an independent expert and overseeing the literature part.

AE: How familiar were you with the Russian avant-garde when you were first traveling to the USSR? The collection of the museum of contemporary art, housed at Palais de Tokyo, included works of Ivan Punin, Mikhail Larionov, and Natalia Goncharova.

JHM: And also Vladimir Baranov-Rossine alongside other artists who immigrated to Paris and then gifted or bequeathed their works to local museums. However, the Russian avant-garde was poorly represented. The collection of Palais de Tokyo did not include a single work by Malevich, Tatlin or Rodchenko.

AE: Who were in contact with when you arrived in the USSR?

JHM: At first, communication with the Ministry was personally managed by Hulten. The chief commissioner for the exhibition appointed on the USSR side was Alexander Khalturin, [6] an official, barely qualified as an art historian. We knew nothing of his background. He proved to be a savvy and resourceful person, who could solve political questions with Moscow officials. He was rather strict and authoritarian with us, but quite open. We could discuss things with him.

AE: A key part of the Paris – Moscow exhibition was allocated to the Russian avant-garde. Was there any controversy on the USSR side?

JHM: No one was against the avant-garde, as they had received approval “from the top.” It was important to achieve a mutually acceptable balance between the avant-garde and figurative art in the wider sense, not just Socialist Realism. Khalturin was very active and slippery. He was always pushing for artists who seemed too academic to us. All of a sudden he might say: ‘The painting section has too much Malevich and Tatlin in it, they should be moved to design and architecture. Tatlin designed sets, so let’s show him in the theater section.” He was always playing with the exhibition layout, shuffling works between different sections.

AE: This was typical of Soviet exhibition principles: to separate an artist’s work and personality. Before discussing artworks with Khalturin, you needed to see them. How was it organized, were you allowed into the secret depositories?

JHM: We had to understand what was kept in Soviet museums in order to know what to request during our negotiations. Discussing names is one thing, specific artworks is another. We were trying to work in two directions at once: from the top through the Ministry of Culture and bottom-up, acquiring as many new contacts among museum colleagues as possible. We were talking to them, trying to persuade them. We were received very well most of the time. Even so, people acting cautiously with us and didn’t get any inventories from them. We understood the level of historical competition between Moscow and Leningrad, so Hulten suggested we visit Leningrad first and meet people from the Russian Museum. We shared our ideas and tried to talk them into working with us, yet most of all we were looking to get into their stores and see the works. Usually we succeeded.

AE: So, it turns out you had Russian informants, not authorized to tell you anything, yet acting on their personal initiative? And thanks to them you got into secret depositories of the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum? This could be interesting to investigate further, as secret sabotage was present in the USSR on absolutely all levels and in every sphere: science, technology, and art were no exceptions. This was seen as resistance to the system.

JHM: There was a circle of people who helped us find the necessary information and choose works with better precision and expertise. For example, Dimitri Sarabianov, [7] who we met regularly. Svetlana Dzhafarova [8] revealed to us works by Malevich that were kept in provincial museums we had never heard of (they were not included in the show in the end). As far as I recall she was fired for doing this: Irina Antonova realised that Svetlana was passing on information that conflicted with the official discourse. There was a Russian researcher working on a book about Tatlin [9] that was published soon after Paris – Moscow. She and her husband were outside the system and helped us a lot. Another person who worked on the exhibition was Vadim Polevoy, [10] who was clearly there to see that the process went well in the political sense. This was strange and it worked out in a way we didn’t expect. Within the exhibition we wanted to reflect on the image of the Revolution and everything that happened after. However, he was always present on site and at some point he made an entire speech about the Revolution, saying that the people behind it were young and romantic and for this reason we shouldn’t pay much attention to this period. In our working group we also had Anatoly Strigalev [11] and Vigdaria Khazanova, [12] who was responsible for the architecture.

AE: Did any of the Soviet specialists come to Paris for the opening?

JHM: Vadim Polevoy and another official from the Ministry of Culture, whose name I don’t remember. Marina Bessonova [13] from the Pushkin Museum was seriously involved in the process and came to Paris several times, whereas Irina Antonova didn’t visit at all. I don’t remember seeing her among the delegation at the opening, but I need to double-check the photographs to be sure.

AE: So Antonova wasn’t involved in choosing the works?

JHM: She got involved at the stage when we decided to organize the second exhibition, Moscow — Paris, and she took over the whole process.

AE: The exhibition in Paris was organized by your team, with advice from Moscow art historians and involvement of officials from the Ministry of Culture.

JHM: I would put the officials in first place, as a lot depended on them. In particular on Khalturin. The checklists of works that we were discussing were compiled in alphabetical order and started with Abram Arkhipov. I was called Mr Impossible at the time, as I was always saying “No, it’s impossible to put works by this artist in the show!”

AE: How did you organize your discussion of the checklists? Did you have photographs of works? Did you plan the layout using photographs as well?

JHM: We used photographs for the discussions. And the layout was planned room by room. Khalturin demonstrated a decent historical understanding of the subject, both in terms of individual works and the general exhibition framework.

AE: After the exhibition was held in Paris did it move to Moscow with the same artworks?

JHM: At first, we planned to ship the exhibition from Paris to Moscow exactly as we installed it initially. All the loans were requested for both exhibitions. But the receiving party wasn’t ready for it: the USSR side decided to have the exhibition two years later than planned. That meant we had to start from scratch.

Before restarting work on the exhibition, I decided to play the spy and travel to Moscow. I met with Irina Antonova at the Pushkin Museum. Khalturin wasn’t there, I didn’t see him once during the installation. The exhibition was curated solely by Antonova. Most of the work was already done, all that was left was installation. One of the trickiest situations involved a huge vitrine from the Paris exhibition, that had involved a lot of effort and was devoted to Trotsky. [14] He had a good relationship with André Breton and was an important figure for the history of Western modernism. We had to fight for a permission to show it in Paris, and in Moscow it prompted a surreal conflict, with Hulten on one side and Khalturin and the Soviet Ministry of Culture on the other. They spent an hour arguing over someone who they didn’t dare to name. The Soviet side insisted that “he” must not be included in the show. No one wanted to give in, but the exhibition opened without the vitrine. Fauchereau and I boycotted the opening, so you won’t be find us in the photos. I also asked Natalie Brunet to get us badges with ice picks to wear. Trotsky, as we know, was murdered with an ice pick in Mexico.

AE: If we compare the catalogues of the exhibitions in Moscow and Paris, it’s very obvious that there were fewer works by the avant-garde in the Moscow edition. For example, some of Rodchenko’s works disappeared.

JHM: The exhibitions in Moscow and Paris were identical and composed of the same sections. There were a couple of cases where we couldn’t obtain certain loans again, but without serious consequences for the exhibition. Also, there was a situation with Tatlin’s Tower. Antonova saw it installed in the main niche of the White Room, the central point of the museum, and was furious. She and Hulten argued. Pontus shouted, “If you move the tower to different place, I will break it!”

The tower belonged to us. Hulten had been head of reconstruction of Tatlin’s Tower at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. They did not have the original plans, only a couple of photographs. Everyone understood that the reconstruction was very approximate. The Centre Pompidou team made the second version, which was more accurate than the first and was eventually shown in Paris and Moscow. [15] Antonova surrendered in the end.

АЕ: And what was the story with Gmurzynska [16] and her gallery?

JHM: I arrived at the museum before the works were delivered and before installation began. I saw two vitrines with works from Gmurzynska’s gallery, installed on Antonova’s instructions. I was surprised, as the works were not included in the contract. We were used to complying with documents and checklists signed at the highest level. Also, there were plans for the opening (or the day after) to hold a fashion show of dresses made of fabrics based on sketches by Popova and Stepanova. That didn’t match our vision at all.

What really astonished us were the fictitious reports on the exhibition opening, compiled by the museum. One of the books on the history of the Pushkin Museum stated that Brezhnev attended the opening, which wasn’t true. He did come, but a month and a half after the opening.

AE: Can you tell us the story of Malevich’s coffin at the Paris show?

JHM: I wasn’t there, I only saw photographs and heard about what happened. As far as I know, Malevich’s coffin was shown only twice, [17] first at Malevich’s solo show in 1978 [18] and then at Paris – Moscow. On both occasions it was part of actions organized by dissident artists. Everyone was telling us crazy things, like the Centre Pompidou was under surveillance and we were surrounded by KGB agents. The Parisian intelligentsia insisted that the Russians had tricked us and the exhibition in Moscow wouldn’t happen, but history proved them wrong.

AE: And that happened thanks to the efficient methods of Pontus Hulten and the pressure he could put on people. You once told me that you had a sense of being on a mission of discovery for this kind of art.

JHM: We were restoring historical truth and that was really moving. It’s a paradox, but intellectuals from Moscow and St. Petersburg knew the Parisian avant-garde much better than the Russian, thanks to the Shchukin collection. A question was raised during a recent conference on Shchukin: [19] why did he buy so many incredible and innovative works in France, yet ignore Russian artists?

AE: Just like George Costakis, who collected and saved works by the avant-garde, including the second tier, and payed almost no attention to the Soviet nonconformists, whose works he could get for free. [20]

JHM: I want to come back to the figure of Alexander Khalturin for a second. We often had lunch or dinner together. Khalturin was always very reserved and didn’t talk much, like a real official. In one of our conversations he mentioned his duties with Tatlin, Malevich, and Rodchenko and said, “At least those people didn’t kill anyone.” I can imagine the risks he had to take and the political maneuvers he had to make. I am sure he complied, but deep down he realized that hiding those works was absurd.

AE: Which can’t be said for Antonova, who didn’t make any maneuvers. She could have shown stronger support for the art.

JHM: But she agreed to have the exhibition at the museum. Who knows how things really were for them? Maybe Khalturin was struggling to find a museum director brave enough.

Sasha Obukhova: The Moscow – Paris exhibition made a big impression on me. I was 13 at the time and I couldn’t believe that art could be like this. In particular I remembered Filonov and Miro. The Tretyakov Gallery didn’t have Filonov on permanent display back then, just like they didn’t have Malevich.

JHM: I remember how we went to the Russian Museum stores and found ourselves in a small room covered floor-to-ceiling with Filonov’s paintings. We knew nothing about him at the time.

SO: He bequeathed all his works to the Russian Museum.

JHM: And made a big mistake: there are very few of his works on the market and this affects his reputation. It’s a challenge to advocate for his legacy. I first realized this when the first Filonov solo show at the Centre Pompidou in 1988 or 1989. [21]

SO: I saw some absolutely incredible Filonov works [22] at the Nukus Museum, which Igor Savitsky founded in Uzbekistan in the Soviet period. Savitsky collected the second tier 1920s and 1930s avant-garde bought up works by dead artists. Those works are now in the museum’s collection and we know nothing about them. There are some remarkable female artists, who I didn’t know before; hundreds of paintings and works on paper, and all of this remains almost invisible in Uzbekistan. But I wanted to come back to the subject of this interview and ask you: when you were working on your famous exhibition Magiciens de la Terre [23] (1989), you included Russian artists. How did you choose the works?

JHM: Back then I director of Bern Kunsthalle. I was in Moscow often and wanted to make an exhibition of nonconformist works. There was an expert board at the Kunsthalle, chaired by Paul Jolles. [24] He was interested in the work of Kabakov, Bulatov, Vassiliev, Shteinberg, and Yankilevsky. I met with all of them. I visited Kabakov’s studio several times and came to the conclusion that he was the most talented of them all. Jolles insisted on a group show of four or five artists, while I wanted to show just Kabakov. I thought that would attract more attention than another “Four artists from…” project, which everyone usually forgets the next day.

I organized the first Kabakov exhibition in Bern in 1985. There were two daily papers in Bern and one of them published a review saying something like: what is Martin trying to say, who needs Russian art? The other review showed more interest, which was exactly what I was trying to achieve, to make people wonder why I chose a Moscow artist. At the time I was also working on Magiciens de la Terre and had a lot of discussions with Kabakov. We exchanged letters. Those letters were delivered by Vladimir Tarasov, [25] who visited Paris for concerts. He told me that Kabakov liked an idea of the project, which meant a lot to me. He was initially included in the list of artists for the exhibition, but I also thought about Eric Bulatov as an important and complex artist, so I decided to invite them both. We showed Kabakov’s installation The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment (1985), which was then for the Pompidou collection.

SO: Did you see it in his studio?

JHM:Yes, and I was amazed: the installation occupied nearly the whole studio, but no one could see it apart from friends.

SO: I heard that while Kabakov was preparing for the exhibition in Bern, he was expecting a truck from Switzerland and some of his works turned out to be impossible to remove from the studio.

JHM: The truck wasn’t coming from Switzerland. One of my friends worked at the Colombian embassy, if I’m not mistaken, and she knew Kabakov. As a member of a diplomatic mission she was much freer to move around the city and her mail was never searched. She took three paintings by Kabakov and they were passed through the window. One of them was sent to Centre Pompidou, two others to Basel museum, or to Bern and Basel, but definitely to Switzerland.

Those were incredible times. Paul Jolles once decided to buy works officially and ship them out of the USSR. And he did it! Some months later he tried to do it again, but it didn’t work. What was the key? The will of a single official, who happened to be more open than others?

SO: I heard that some things were made possible thanks to Tair Salakhov, [26] head of the Artists’ Union at the time. Among other things he signed export permits. Some people believe that he was the first to start lifting the Iron Curtain. I am not sure how fair it is to say that, as in 1988 many things were much easier to organize.

JHM: In 1988 things were certainly much easier. Kabakov first left Russia in late 1987, traveling to Austria under a grant program. Do you know how he got his visa? He applied for a USA visa in Vienna. [27] He was lucky to meet an official who was eager to help. His visa didn’t come instantly, but was delivered much faster than expected.

SO: You played an important part in the lives of Moscow artists, when you curated the 3rd Moscow Biennale in 2009. How did it go? Who invited you?

JHM: I was invited by Joseph Backstein. I don’t know why he chose me. My wife and I came to Moscow during the Year of French culture in Russia. We stayed at the Baltschug Kempinski hotel. I met Joseph and he suggested I curate the biennale. I refused due to my schedule: I was preparing a big show in Paris and couldn’t work on two projects at the same time. I returned to the hotel, spoke to my wife and she said, “Are you crazy? Accept immediately!”

SO: A woman’s role in history!

JHM: I called Joseph back and told him that I changed my mind. In my opinion the first two biennales [28] had a strange structure. The main project was created by a team of curators and hardly included any Russian artists. Their works were always part of the parallel program.

SO: Russian artists were included in the main exhibition. There were few, but they were present.

JHM: In any case I told Joseph from the very beginning that I would only curate this project if I was allowed to include Russian artists in the main exhibition, not separately from other participants.

SO: The generation of artists working in the 2000s was different from that of the early days of perestroika. Russian art wasn’t as popular as German or French. How did you do your research for the biennale?

JHM: I wanted to meet as many artists as possible and discover the new generation. I was disappointed by what I saw. That’s why I mainly chose artists of the perestroika period and very few of the new generation. I think Ivan Chuikov was surprised, when I picked his old installation Split Identity (1993–2009), which he had repeated numerous times. But I liked it and persuaded him to lend that work for the exhibition.

SO: This was one of the best exhibitions in Moscow in recent decades.

JHM: I’ve heard that reaction before and I’m always very flattered. It was a great pleasure to work on that biennale.

SO: It demonstrated a will to make a statement about art, which is a rarity. And my last question: what is your impression of Russian art that you have seen during your current visit to Moscow? Do you see works by Russian artists at international exhibitions? How is Russian art represented in that context?

JHM: I think that Russian art today attracts less interest than before. Cosmoscow art fair didn’t impress me much. Also, there is very little information on what is happening in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Fifty years ago we knew much more about art from Russia than we do today. It is not present on the European or American markets, which is sad. That is probably the reason.

SO: In recent years there were no major exhibitions of Russian art abroad. Might this be political?

JHM: I don’t think so. I don’t know how to explain it. The work of Western museums is dictated by fashion. There are endless extremely boring exhibitions of Chinese art opening in France today, and no one cares about Russia. Curators are usually lazy and have little interest in what is going on around them. They don’t want to make individual statements, for their shows they take whatever they saw at other biennales. It’s disappointing. The reasons are, again, market-related. Galleries that work in Russia do not collaborate with their colleagues in the West and do not look to establish the exchange that is so vital. They are focused on the situation in Russia and rarely show art from other countries, which makes it impossible for them to appear within the international art context.

SO: It seems to me it’s not about the market, which has never been strong in Russia, but the support the government gives to such art. Today it’s very weak, but there’s still a chance. If the market improves, the government may pay attention to art.

JHM: I think you’re right.

SO: Thank you for the interview.

Notes

[1]. Pontus Hulten (1924–2006) was a Swiss and French curator. In 1960 he became the first director of Moderna Museet, the museum of modern art in Stockholm. In 1977 he was co-founder and the first director of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. In 1985 he was one of the initiators of the Institut des hautes études en arts plastiques in Paris.

[2]. George Costakis (1913–1990) owned a collection of Russian and Soviet avant-garde comprising over 2,000 works by artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Vasily Kandinsky, Ivan Punin, Liubov Popova, and Natalia Goncharova. In 1977 Costakis and his family emigrated from the USSR to Greece. According to the documents signed by Costakis and the Ministry of Culture of the USSR in the same year, part of his collection (834 works) was given to the State Tretyakov Gallery. The remaining part (1,277 works) was acquired by the Greek State between 1988 and 2000 and is currently a part of the State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki.

In the late 1970s, George Costakis’ collection became known internationally. As a foreign citizen, Costakis had been allowed to travel outside the USSR since the late 1950s, where he met émigré artists and gave lectures on the avant-garde accompanied by images of works from his collection.

See: Costakis, G. Мой авангард. Воспоминания коллекционера. [My Avant-Garde. Memories of a Collector]. Moscow: Modus graffiti, 1993; Costakis G. Коллекционер. [Collector]. – Moscow: Isskustvo- XXI vek, 2015.

According to Greek art historian Maria Tsantsanoglu, works from the Costakis collection formed the central part of the Paris – Moscow and Moscow – Paris exhibitions.

See: Tsantsanoglu M. “Коллекция Георгия Костаки в Государственном музее современного искусства города Салоники. Открытие русского авангарда миру. [George Costakis’ Collection at the State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki. Revelation of the Russian Avant-Garde to the World]” in George Costakis. К 100-летию коллекционера. Каталог выставки [To Mark the 100th Birthday of the Collector. Exhibition catalogue]. — Moscow: State Tretyakov Gallery, 2014, p. 30.

[3]. Werner Spies is a German art historian, art critic, curator, and lecturer. He lived and worked in Paris from the 1960s. In 1971 he published the first catalogue raisonné of Picasso’s sculptures. In 1975 he curated the first retrospective of Max Ernst at the Grand Palais, Paris. From 1975 to 2000 was director of Düsseldorf Art Academy and from 1997 to 2000 he was director of the Centre Pompidou.

[4]. Raymond Guidot is a French design historian, curator, and lecturer. He is the author of Histoire du Design 1940–1990 (1994), which has been reprinted numerous times.

[5]. Serge Fauchereau is a French art historian and curator of the exhibitions Futurismo et Futurismi (Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 1986), Europa, Europa. Das Jahrhundert der Avantgarden in Mittel- und Osteuropa (Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, 1994), and others.

[6].Alexander Khalturin was a museum worker and government official at the Ministry of Culture of the USSR. During work on the exhibition Paris – Moscow he was head of visual arts and protection of cultural heritage at the Ministry of Culture.

[7]. Dimitri Sarabianov (1913–2013) was a Soviet and Russian art historian, Doctor of Art History (1971), and professor (1973). Member of the Artists' Union of the USSR (1955). Author of monographs on Sergey Malyutin (1952), Pavel Fedotov (1969, 1985), Semyon Chuikov (1958, 1976), Kazimir Malevich (with Aleksandra Shatskikh, 1993), Robert Falk (2006), and others.

[8]. Svetlana Dzhafarova is a Soviet and Russian art historian. She was a research fellow in the Art Theory department of the Russian Institute for Cultural Research until it closed in 2014.

[9]. Probably Larisa Zhdanova (1927–1981), editor of the catalogue Татлин. Заслуженный художник РСФСР [Tatlin. Honoured Artist of the RSFSR] (Moscow, 1977) and author of the books Tatlin (Budapest, 1983), Tatlin (London, 1988), Tatline: Masterskaia Tatlina (Paris, 1990) and other.

[10]. Vadim Polevoy (1923–2008) was a Soviet and Russian art historian. Doctor of Art History (1971), Professor (1973), full member of the Academy of Arts (1990). From 1974 to 1991 he was a head of the editorial board of the almanac Sovetskoe Isskustvoznanie [Soviet Art History].

[11]. Anatoly Strigalev (1924–2015) was a Soviet and Russian art and architectural historian, researcher of the Russian avant-garde. He edited books and catalogues on Konstantin Melnikov and Vladimir Tatlin.

[12]. Vigdaria Khazanova (1924–2004) was a Soviet art historian. She is the author of over a dozen books and numerous research papers on the architectural avant-garde in the postwar USSR.

[13]. Marina Bessonova (1945–2001) was a Russian art historian, critic, and museum worker. In 1970 she became a research fellow at the State Pushkin Museum. She specialized in naïve art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and was editor of a number of exhibition catalogues, including (Марк Шагал. К столетию со дня рождения [Marc Chagall. To Mark his 100th Birthday] (1987) and Государственный музей изобразительных искусств им. А. С. Пушкина. Каталог картинной галереи [Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Catalogue of the Painting Gallery] (1986). She curated the exhibitions Henri Matisse (Pushkin State Pushkin, Moscow; State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, 1993), Picasso’s Cubism and the Finnish Avant-Garde (Retretti, Punkaharju, Finland, 1994), The Non-Figurative in Russian Art. From Kandinsky and Malevich to the Present Dayn(State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 1994), and others.

[14]. The Paris – Moscow exhibition catalogue contains at least four mentions of Leon Trotsky in the context of publications that featured his works or were related to him. The literature section of the exhibition in Paris included: 1. A collections of poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky in French translation, published in 1930 with a foreword by Trotsky (also shown in Moscow).

2. Demain magazine (no. 19, November 1927), containing a transcript of a speech by Trotsky.

3. Révolution surréaliste magazine (no. 15, October 15, 1925), containing Trotsky’s article on Lenin.

4. Clarté magazine (Trotsky is mentioned in the catalogue as one of its authors).

The Moscow – Paris exhibition catalogue does not mention Trotsky.

[15]. See: https://www.centrepompidou.fr/cpv/resource/cqGrB5n/rezKeyr.

[16]. The gallery owned by Polish immigrant Antonina Gmurzynska, founded in 1965 in Cologne, specialized in surrealism, constructivism, and the Russian avant-garde. The gallery currently has spaces in Zurich, Zug, and New York. Krystyna Gmurzynska, Antonina Gmurzynska’ daughter, became director in 1986.

[17]. This is a reference to an action by émigré unofficial Soviet artists that happened at least twice, in Paris (1979) and New York (1981). Igor Shelkovsky participated in the action in Paris and wrote:

“Here [in Paris] there was a two-day colloquium, “Culture and the Communist State,” then there was an idea to demonstrate outside the Beaubourg [Centre Pompidou], where the exhibition Moscow – Paris (sic) was taking place. Two Polish guys suggested we make a coffin and carry it in memory of everyone murdered. I liked the idea and suggested making Malevich’s coffin, so it would be more related to the exhibition. We made Malevich’s coffin in two days. The result was a beautiful suprematist coffin, all that was left was to show it. No one knew how things might go. There were rumors that the police were trying to prevent anti-Soviet demonstrations so as not to annoy the Soviet elite. There were some special conditions imposed by the Soviet side with regard to this exhibition.

There were six handles on the coffin and it was very heavy. We picked it up and walked. Ahead of us were Natasha Gorbanevskaya and some French leftist intellectuals holding up the banner “Here lies Russian avant-garde, killed by Soviet socialist realism.” We marched across the square in front of the Beaubourg, where there are usually people fire-eating, playing saws, many conjurers, jugglers, singers, and crowds of people. We processed across the whole square and everyone was surprised by our coffin. We approached the museum doors. No one stopped us. We entered, there were no obstacles. Through the glass pipe, with escalators inside, we went from floor to floor to the fifth level, where the exhibition was. We lifted the coffin on our shoulders, went through security, disregarding the weak attempts to stop us (there were 20 or 40 of us, we didn’t buy tickets and we were a crowd carrying a huge object from outside). For some reason it seemed natural to place the coffin next to Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International. We went downstairs and carried the coffin into a room where a conference about the exhibition was taking place. The demonstration participants joined the discussion. That’s how our happening went.”

From the artist’s correspondence with А–Я magazine. 1976–1981. Volume 1. Edited by Igor Shelkovsky. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2019, p. 344.

From Victor Agamov-Tupitsyn and Margarita Masterkova-Tupitsyna’s memories of the action in New York:

“[Victor Agamov-Tupitsyn]: In 1981 Igor Shelkovsky, editor of А–Я magazine, arrived in New York. Together with Aleksandr Kosolapov they made a replica of Malevich’s suprematist coffin, which became a ‘sacred object’, the epicenter of ideological rituals played out in the 1980s by members of Kazimir Passsion group at P.S. 1 and The Kitchen. The group’s first action took place in 1981. It was a demonstration in front of the Guggenheim Museum, which was showing the Russian avant-garde at the time. There were Shelkovsky, <…> Bakhchanyan,the Gerlovins, you and me [Victor Agamov-Tupitsyn and Margarita Masterkova-Tupitsyna], Khudyakov, Druchin, Urban, and Kosolapov with his wife (Bardina). I read Kharms’ poems on the death of Malevich, we were all shouting, climbing telegraph poles, and demanding a halt to the commercialization of the dead, calling it necrophilia and the second death of the Russian avant-garde, in particular of Malevich. That is when the Kazimir Passion was born.

Margarita Masterkova-Tupitsyna: Yes, it’s hard to imagine that in the early 1980s there were people who could be brave enough for this kind of a protest. [. . .] Anyway, straight after the action at the Guggenheim Museum the suprematist coffin was taken to the CCRA [Center of the Contemporary Russian Avant-Garde, founded in New York in 1981 by Norton Dodge], where it gradually blended into the exhibition Russian New Wave. Among visitors to that exhibition was Ann Magnuson, the action artist and initiator of the performance festival at PS1. She saw the coffin and asked whether it was possible to make something ‘around this object’. This started a series of performances by Kazimir Passion group, that created a whole new paradigm in the relationship between the historical avant-garde, [. . .] socialist realism, and the neo-avant-garde’.

Tupitsyn V., Tupitsyna M. “Moscow – New York,” World Art Muzei, 21, 2006, pp. 13–14.

[18]. Malevitch: exposition rétrospective, Centre Pompidou, Paris, April 14–May 15. Curated byJean-Hubert Martin.

[19]. The reference is to the conference Sergei Shchukin Collection: Its History and Influence on the International Context, which took place September 11–13, 2019 at the Pushkin Museum.

[20]. In fact, George Costakis had a large collection of works by nonconformist artists, including Vladimir Yakovlev, Igor Vulokh, Anatoly Zverev, Francisco Infante, Dmitry Krasnopevtsev, Lev Kropivnitsky, Dmitri Plavinsky, and others. See: George Costakis. К 100-летию коллекционера. Каталог выставки. [To Mark the 100th Birthday of the Collector. Exhibition catalogue]. Moscow: State Tretyakov Gallery, 2014, pp. 284–311.

[21]. Filonov, Centre Pompidou, Paris, February 15–April 30, 1990.

[22]. The Savitsky State Art Museum of the Republic of Karakalpakstan was founded in 1966 in Nukus (Uzbekistan) by Soviet art historian, ethnographer, and conservator Igor Savitsky (1915–1984). The museum collection comprises over 90,000 works, including by the Russian avant-garde, and is considered to be one of the most important collections in terms of value and size.

[23]. The exhibition Magiciens de la Terre was a legendary project that Jean-Hubert Martin curated in 1989 at the Centre Pompidou and the Grande halle de la Villette, Paris. The exhibition brought together works by contemporary artists from different continents, the proportion of Western and non-Western artists being 50:50. It marked a post-colonial turn in curatorial practices, yet the team was criticized for failing to escape colonial optics in their choice of works and display methods, notwithstanding their motivation to go beyond Western-centrism.

[24]. Paul Rudolph Jolles (1919–2000) was a Swiss diplomat and politician. He was a director (1966–1984) and state secretary (from 1979) at the Federal Department of Economic Affairs. He was a president of Bern Kunsthalle and of the administrative board at Nestlé, where he worked on creating a corporate collection and a charitable foundation. In the 1970s he began visiting the USSR, where he was introduced to the circle of Soviet non-official artists. See: Frimmel S., “Арина Ковнер и Пауль Йоллес — швейцарские коллекционеры советского нонконформистского искусства [Arina Kowner and Paul Jolles – Swiss collectors of Soviet nonconformist art].” URL: https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/110505/1/Frimmel__Vortrag.pdf.

[25]. Vladimir Tarasov is a Soviet and Lithuanian jazz musician and installation artist.

[26]. Tair Salakhov is a Soviet, Azerbaijani, and Russian painter, one of the founders of the so-called “severe style.” From 1973 to 1991 he was first secretary of the Union of Artists of the USSR. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, thanks to his direct involvement, solo exhibitions by artists such as James Rosenquist, Günther Uecker, Francis Bacon, and Jannis Kounellis were shown in Moscow at the Central House of Artists.

[27]. From 1986 Vienna became a transit point for Soviet émigrés traveling to Israel, the USA, and other countries. See: Vatlin, A. Австрия в ХХ веке: учебное пособие для вузов [Austria in the 20th Century: Teaching Material for Universities] Moscow: Direkt-Media, 2014.

[28]. On the 1st and 2nd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary art see:

https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/event/EHZ, https://russianartarchive.net/ru/catalogue/event/EXMF.

Interview by: Andrei Erofeev, Sasha Obukhova

Interview date: September 14, 2019

Translation from French and English, notes: Valerij Ledenev