This publication about Cyber-Femin-Club, a phenomenon of 1990s St. Petersburg culture is based on quotes by the founders and key ideologists of the project, the media philosopher Alla Mitrofanova and the art historian and curator Irina Aktuganova.

The quotes are accompanied by visual materials from the Irina Aktuganova and Sergey Busov archive, which became part of Garage Archive Collection in 2018.

The selection of quotes, visual materials, and comments was made by Maria Udovydchenko, conservator of the Irina Aktuganova archive at Garage Archive Collection in St. Petersburg.

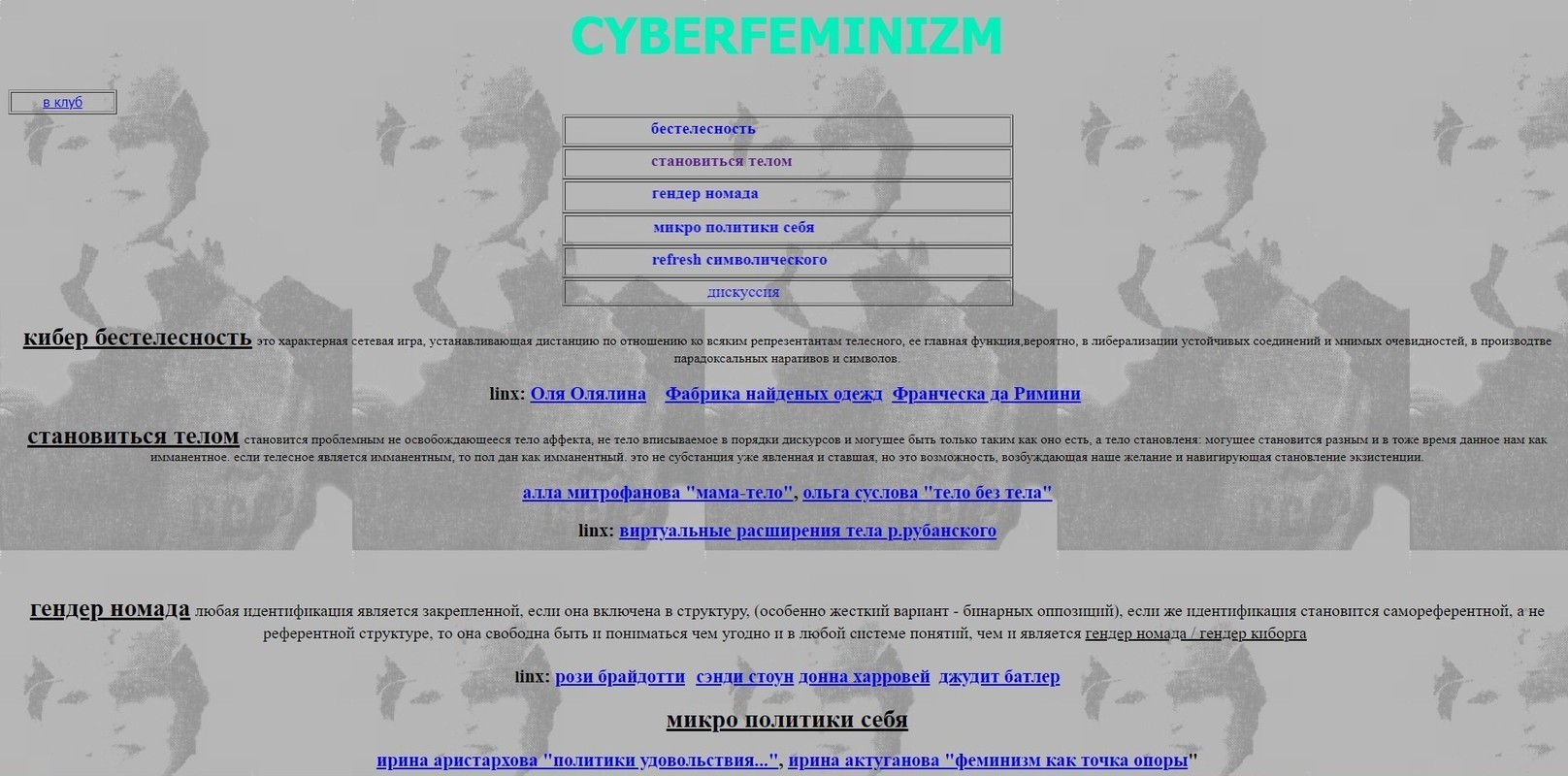

I. Quote from archival document: Cyber-Femin-Club, Quotes, 2010. Garage Archive Collection (Irina Aktuganova and Sergey Busov archive)

“In 1994, the face of St. Petersburg’s art scene changed radically with the advent of Cyber-Femin-Club at Gallery 21 at Pushkinskaya 10.* Cyber-Femin-Club began its activity with a landmark event for Petersburg art—the mooring of the German cyberpunk ship Stubnitz…** The festival of electronic and media arts organized on the ship by Alla Mitrofanova became a demonstration of new forces on the Petersburg art scene, where a techno r(av)evolution was raging. Cyberfeminists engaged the community in the creation of the first Russian art CD-ROMs, the online magazine Virtual Anatomy, while also organizing numerous seminars, conferences, educational programs, and a free Internet café for women and artists.

Andrey Khlobystin, “Women's Unions of St. Petersburg” in The Female Face of St. Petersburg Art (St. Petersburg: Museum of Nonconformist Art, 2000)

*Different times are given for the launch of Cyber-Femin-Club. Some documents mention that the club appeared in 1995. This date is indicated in the document “List of Projects and Exhibitions of Cyber-Femin-Club, implemented from 1996 to 2005.”

**The Stubnitz ship of the arts, which arrived in St. Petersburg in July 1994, created a real stir. The international team of organizers, artists, and musicians presented the audience with the most cutting-edge forms of media art and contemporary electronic music. The festival lasted ten days and featured exhibitions, conferences, and performances mixed with vibrant parties. While the Stubnitz was in the city, it was visited by around 3,000 people and, most importantly, this project marked the beginning of friendship and creative cooperation between Irina Aktuganova and Alla Mitrofana, the founders of Cyber-Femin-Club.

II. Quote from archival document: Irina Aktuganova, Draft of the article “Cyberfeminists and Cyberfeminism and Cyber-Femin-Club,” 1999. Garage Archive Collection 9Irina Aktuganova and Sergey Busov archive)

“Russian Silver Age philosophers knew that women happily combine two features, a thirst for novelty and an instinct for self-preservation. The first helps a woman to explore new social spaces in a pioneering way, and the second, to avoid self-destruction.

Back in the early 1990s in Petersburg, it was girls who began to play with the Internet and new media in general as a socio-cultural space. In the second half of the 1990s they named themselves cyberfeminists.

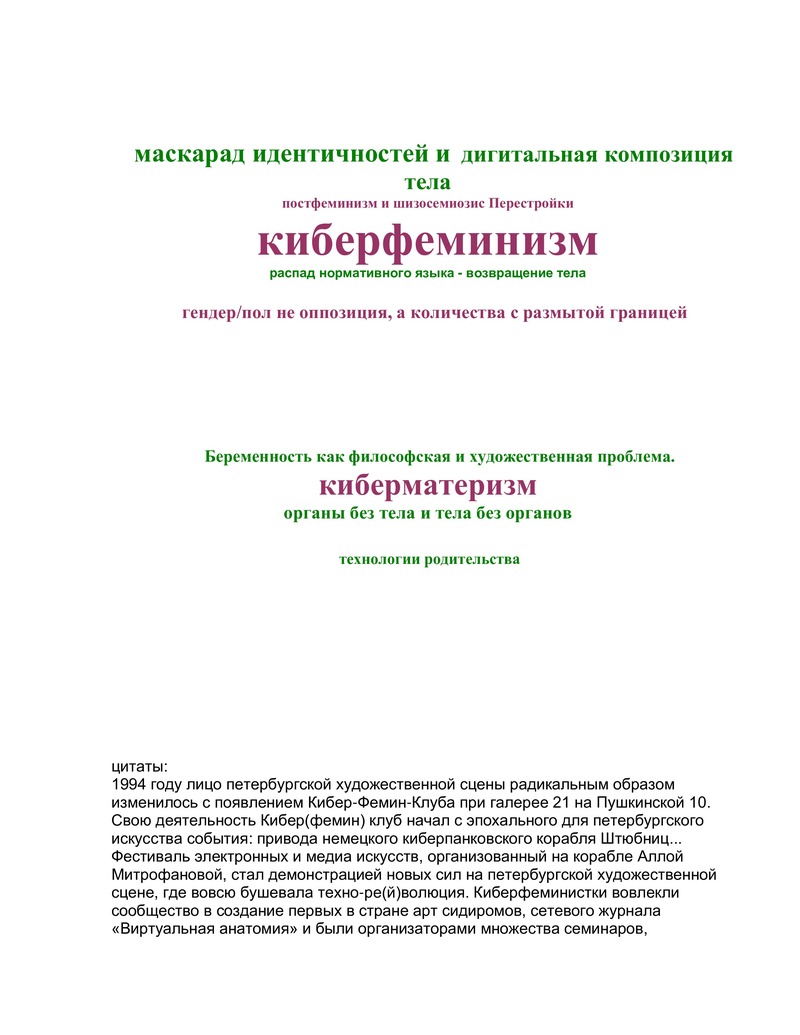

The implementation of Gallery 21’s theoretical project Post-Informational Utopia and the publication of the Novy Obyvatel (New Inhabitant) newspaper (the titles of which speak for themselves) took place in the time interval between virtual Internet projects and cyberfeminism.

Thanks to the intellectual efforts made during the implementation of these projects, the following list of synonyms appeared: post-informational, non-conceptual, non-verbal, non-intellectual, non-binary, non-audiovisual, sensory-bodily, slow experience, debt, pain, existential, ontological, non-symbolic, feminine, cyberfeminism, unarticulated, unambitious.

In drawing on cyberfeminism, we are drawing on something that for our culture is nonsense and emptiness. It is non-discursive and indefinable. For those of us who have survived the death of language (words mean nothing), this is one of the pseudonyms of reality itself, which we, thanks to previous experience, have peeled out from under cultural layers and interpretations, as it were. On the other hand, thanks to the term “cyberfeminism,” the same conservatives see us as frisky pseudo-avant-gardists in the Western manner. And since the post-informational cyberfeminist is lazily engaged in self-promotion and, according to the rules of the game, should not engage in self-conceptualization and pumping ambitions, then there is simply no one to shed light on this whole confusing proposition. In our context, a cyberfeminist is a mature yet radical woman to such an extent that no one can recognize it: she has lost interest in playing art and is raising children, walking, trying out various healing methods, and shying away with disgust from the words “Internet” and “TV.” A genuine Russian cyberfeminist is one who understood something about cyber, about feminism, about gender, and about liberalization, and became so bored that she just wanted to live.”

III. Quote from archival document: Irina Aktuganova, “Woman in the Underground,” 1998. Garage Archive Collection (Irina Aktuganova and Sergey Busov archive)

“The Russian socio-political processes of the last decade have pushed women to the periphery of political and social life. On the one hand, this is an unfortunate fact. On the other, I also see positive aspects in it. Having become marginal, a woman has acquired a lot of advantages, such as increased adaptability, the desire for self-awareness, breadth of vision, tolerance, and a higher level of activity. Since almost all spheres that are not related to big business and big politics have become marginal, a wide field of activity has opened up for women, where they can build their own female subculture in a completely uncensored and creative way…

Eighteen months ago, being completely exhausted by the inertia of “contemporary art” and looking for a concentration of live, young energy, I discovered for myself the culture of women’s organizations…*

These organizations help women to get ready for childbirth, to give birth, to provide their children with education and medical treatment, to receive legal and psychological assistance, to dress for less, to feed a large family, to find temporary shelter in case of problems with an apartment or husband, to acquire computer literacy, to use the Internet,** to practice needlework or other creative activities, to open a personal exhibition, to make a career, to learn languages, to travel abroad, to send a kid to study in America, to recover from drug addiction, to save their son from the army, to run for parliament or the presidency. And this is not even close to a complete list.”

*One of the interesting and relatively unexplored aspects of Cyber-Femin Club's work is assistance to various women's organizations, including the League of St. Petersburg Women Voters and Soldiers' Mothers of St. Petersburg. The League of Women Voters advised women on legal issues, assisted in applying for grants, and helped them navigate the nuances of the election campaign. The human rights organization Soldiers' Mothers of St. Petersburg supports conscripts and servicemen in need by providing legal advice. In the 1990s, Cyber-Femin-Club members assisted both organizations in the development of home pages, as evidenced by archival documents containing visual and textual materials from these websites.

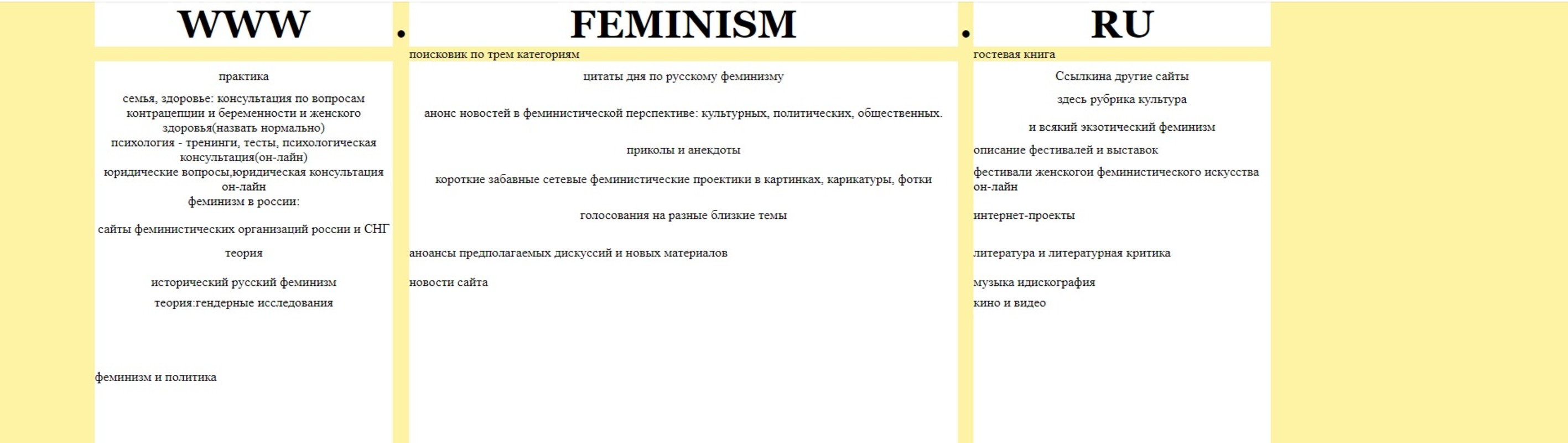

**Regular computer literacy classes for women were held at Cyber-Femin-Club, located in the space of Gallery 21 at Pushkinskaya 10. In the mid-1990s, when home Internet was a rarity, Cyber-Femin-Club provided access to the Web and to electronic mailboxes and advised on creating personal sites. The archive includes photographs taken during those classes.

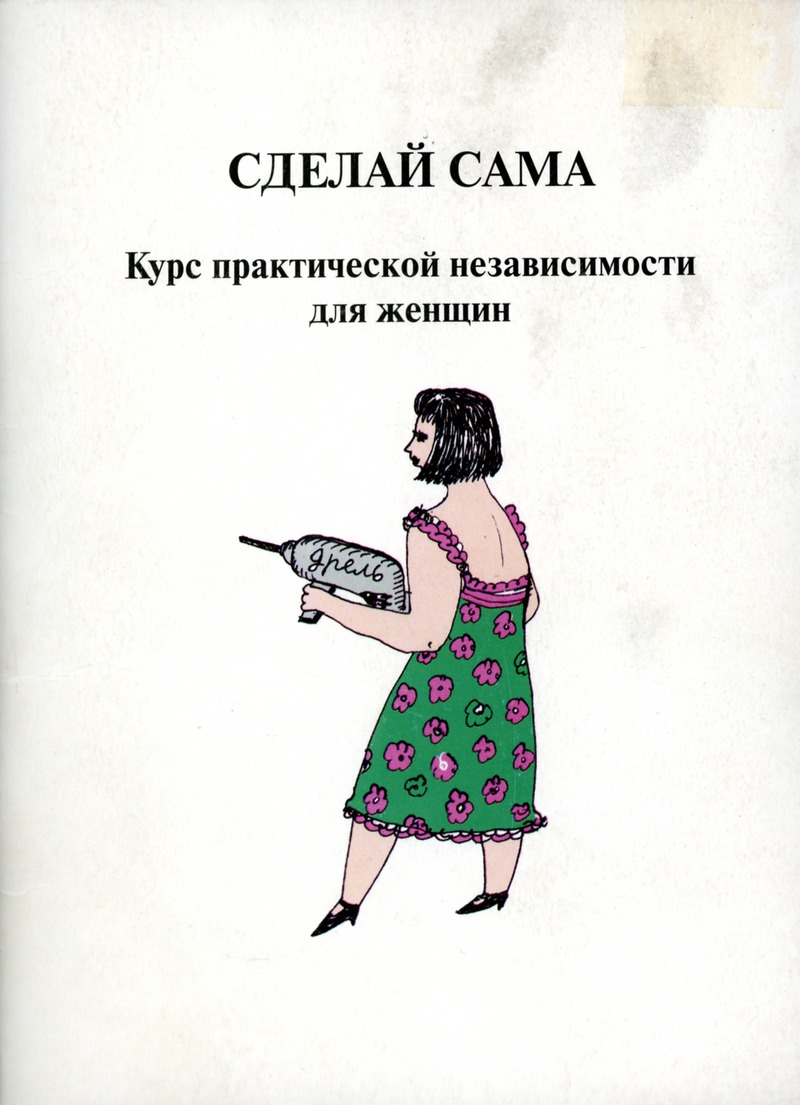

These classes subsequently grew into a whole course, created by women for women. In 2004, cyberfeminists, with the support of the Soros Foundation, launched the Do-It-Yourself Course of Practical Independence for Women, where they taught students how to do minor household and electrical appliances repairs, work with computers, and learn about home refurbishment. The course was so popular that in 2006 a second stream was launched, and the educational program was supplemented with classes in car repair and maintenance. Unfortunately, classes did not continue, but the course resulted in the publication of a manual featuring Irina Aktuganova’s drawings.

Over the years of its existence, the creators of Cyber-Femin-Club took part in several major international festivals and conferences on communication of women's communities on the Internet and the new digital reality, including Cyberfeminist International 2 Festival (Austria, 1997) and the Cyberfeminizm NY–SPb teleconference (1997), while also running a number of educational initiatives on telecommunications and computer literacy for women, including seminars and practical classes. Media activists from Australia, Austria, Canada, Slovenia, France, and Croatia visited St. Petersburg at the invitation of the Club. From the late 1990s, thematic exhibitions, actions, and performances were regularly held at Cyber-Femin-Club, which was located in the space of Gallery 21, including the exhibition Boundaries of Gender, organized jointly with the Moscow Center for Contemporary Women's Art, and a series of exhibitions of personal artifacts from the archives of artists Olga Tobreluts, Bella Matveeva, and curator Ekaterina Andreeva. In 1998 and 1999, the art actions Bitch of the Year (1998) and Bitch of the Century (1999), organized in collaboration with the art group Money took place here, as did many other events that formed a significant page in the history of St. Petersburg art of the 1990s and 2000s.